Mentoring at a Social Distance: How 4 Programs Are Creating New Ways to Connect Students and Professionals During COVID-19

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

When Jason Wiegand agreed to run a new mentoring program in Iowa last year, he wondered how difficult it would be to begin during a pandemic that was actively encouraging social distancing. It turned out that just one trip to a Starbucks showed him the need for mentors was strong and the restrictions of COVID-19 might even become an advantage.

A barista told him she was stressing about her classes to become a dental hygienist. Because that field is in high demand, she was a perfect match for the Future Ready Iowa Virtual Mentoring program that Wiegand was creating. Iowa offers students scholarships for a wide range of careers deemed to be in demand; those who study subjects ranging from agriculture business management to welding are eligible. Anyone taking classes through Future Ready can get a mentor upon request.

While Wiegand was wondering how to get his new initiative off the ground, this chance encounter was a perfect test. He explained the program and its benefits to the Starbucks worker, and before he knew it, he had his first mentee.

Mentoring is “a reflection of what we need,” said Wiegand. “It’s how people get jobs and get through programs.”

Those benefits, both explaining the ins and outs of a new profession and connecting with experienced workers, are echoed in programs throughout the country. Amid a global pandemic, mentoring seems as popular as ever. Existing programs have gone virtual, in some cases expanding, while a rash of new services have popped up.

“Mentoring programs have really transitioned,” said Sarah Schaefer, executive director of MENTOR Minnesota in Minneapolis. “Programs are getting creative. They are uniquely able to connect people to resources they critically need.”

Nationally, statistics show the value of mentorships. K-12 students who meet regularly with a mentor are 52 percent less likely to skip school and 46 percent less likely to start using illegal drugs than peers without mentors. And a Sun Microsystems study showed that mentees are 20 percent more likely to get a raise and five times as likely to be promoted as workers without mentors.

Here’s a closer look at four mentoring programs around the country. Some, like Wiegand’s, started during the pandemic, while others had to change their approach to go remote. But all the programs prove mentoring’s worth, pandemic or no, as students, adults and mentors connect to learn skills and share advice.

Future Ready Iowa

For Jason Wiegand, it is ironic that he is helming a mentoring program that requires students to know what field they want to pursue before they sign up.

“I changed my major three times” before earning a degree, he recalled.

The program grew out of Future Ready Iowa, a five-year-old effort to build the state’s talent pipeline by encouraging residents to get education or training beyond high school. Under Future Ready, the state offers students two types of free scholarships for pursuing higher education in high-demand fields, such as information technology or health care.

Just a year into the program, 53 mentors are guiding about 95 students, covering 15 colleges throughout the state. The free courses entice students working menial jobs to train for a better career, Wiegand said.

The average age of participants in the program is 31, and many are non-traditional students. About a quarter are from underrepresented groups, and one even has a master’s degree.

Wiegand pushes the mentees to create a long-term relationship with mentors, going beyond resume reviews and mock interviews to understand the day-to-day work of the profession, learn which organizations are important to join and hopefully, once pandemic rules ease, participate in in-person workplace tours.

That student with the master’s degree is Chantal Shirley. After becoming a teacher and working for four years, Shirley realized she wanted to “navigate into something that was a passion.”

When she first went to college, she herself was a mentor, working with students on the autism spectrum. As she tutored them in math and some computer-related classes, she got bitten by the programming bug. “I bought a textbook and was studying programming while I earned a master’s in English,” she said. Once she decided to switch careers, she started taking classes at Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids.

As someone who identifies as a lesbian Black woman, she quickly realized “there aren’t a lot of folks like me” in programming. Getting a mentor helped her understand the profession and learn which computer languages are in current demand.

While she hasn’t met her mentor in person yet, online conversations work well because they live on opposite sides of the state, she said. “He’s given me advice regarding norms in the industry, offered feedback on my own development, looked at software I’ve built. He’s given me advice and told me what to read,” she said. “I never had someone take a professional interest in me.”

Because Shirley has been able to connect on a human level with her mentor, it “makes the program feel meaningful. You don’t feel like a project,” she added.

ManCode in Minneapolis

Quanda Arch knew she would need a particularly good draw to entice students 12 to 17 to 2½-hour Saturday morning virtual computer programming sessions after they spent the whole week attending school on Zoom.

Luckily for Arch, community resource liaison at Minneapolis’s Phyllis Wheatley Community Center, she was able to offer students a peek behind the scenes of Xbox, led by Microsoft employees.

The impetus for the program began when Microsoft manager Phil Terrill moved from Redmond, Washington, to St. Paul, where he grew up. Terrill is the creator of ManCode, a one-day program he started in Redmond that aimed to introduce Black boys to computer programming. But in St. Paul, pandemic limitations led Arch and Terrill to rethink the idea. They came up with a 12-week program that takes students through everything from life skills to financial literacy to coding, web design and computer security.

“It’s amazing that 30 students got up every week to do this, especially after half of them were gaming all night,” Arch said — including her own son.

“The excitement of the mentors and the energy they gave” kept students interested, she added. When Microsoft employees detailed the various careers that are affiliated with Xbox, Arch said, “It opened their eyes. They realized, ‘I can not just be a player, but I can participate and create games.’”

Parents Helping Parents

The setup of most mentor programs is simple: one group of experienced professionals coaching students or less experienced workers. But when the pandemic shut down in-person schooling and forced many parents to help their children connect with, and succeed at, school, it became clear to Francisco Meza that a new model was needed.

Meza is the director of state and federal programs at California’s Whittier Union High School District. He saw Spanish-speaking parents struggling to help their children with virtual learning and worried that these students would abandon their college dreams.

With no money for a new initiative, he decided to crowdsource help from families, creating a group of parents who could mentor each other in whatever role was needed, from helping with technology to unraveling the mystery of the federal student aid application. Less than a year after Parent Mentors for the Road to College Success started, the program is growing to other schools in the district and garnering international attention from educators.

“We help in the background,” said Meza. “It’s all voluntary and doesn’t cost the district anything.” The district did distribute computers and hotspots to parents in the program who needed them, he added, as he doesn’t want parents having to share either with their children.

“Some parents have never touched a keyboard,” Meza said. “They come from another country and have no idea what FAFSA is.”

Diana Vargas was one of those parents. “A year ago, I didn’t know what Zoom was,” she said. The district trained her and other parents about some basic technology issues, and now she’s making videos in Spanish to share what she has learned.

Her big goal is to have her children attend, and complete, college. “There’s so many things to learn. I think some parents don’t encourage their kids because they don’t understand” the application process, she said. School officials have broken down college applications step by step, helping parents avoid being overwhelmed, she added.

While it’s early to judge the program’s success, Meza said he recently checked the grades of students whose parents are mentors. “No one had lower than a B average,” he said proudly. “And that’s during remote learning.”

Future Architects

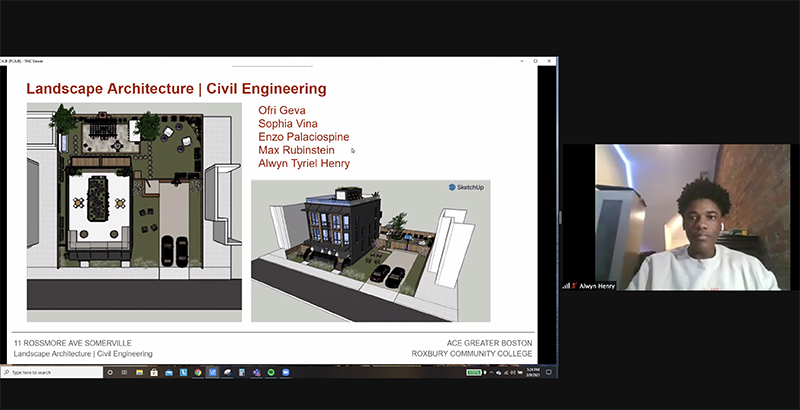

Perhaps no mentoring program was more hands-on pre-pandemic than ACE Mentor Program of Greater Boston. This affiliate of the national group aims to help teens understand and gain experience in architecture, construction and engineering.

Typically, each year, the students would focus on a project, helped by mentors from colleges and firms in the city.

Prepandemic, 97 students would gather in five locations throughout the city to design a library. When the pandemic canceled face-to-face activities, Jennifer Fries, the program’s executive director, decided to gather up the supplies students needed for the project and mail them directly to participants.

Students received sketchbooks, tracing markers, toothpicks and more. “It was a nice treat” that connected students more closely to the program, she said.

With competition from sports and extracurriculars gone, the 16-week program swelled to 165 students this year. “The one thing that worked really well was we were able to enroll students who were farther away,” she said. In the past, it would be a hike for some students in north Boston and other outlying areas to come into the city each week.

Fries acknowledged that mentors had a harder time connecting with students over Zoom and often had to coax them to turn on their cameras. But most students ultimately completed this year’s project of designing a house.

Research from past years shows that students in the program are more likely to become engineering majors when they attend college, with Hispanic and Black students from the program twice as likely to choose that major than those who weren’t in the program.

Even with the problems of working remote, students were able to learn and practice the basics of architecture, construction and engineering, Fries added. “They benefited from it, and it will help them with their college studies.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)