Mendel: Not 1 State is using ESSER Funds to Address Suspensions, Expulsions or Arrests of Students at School. There’s Still Time to Fix That

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a nightmare for teenagers.

The U.S. surgeon general and the American Academy of Pediatrics recently declared a nationwide adolescent mental health crisis, as did the president of the United States. Academic achievement tests show wholesale learning loss. School attendance has plummeted. And these difficulties are being felt most among students who were already behind before COVID — youth of color, those with disabilities and those from low-income communities. Though no reliable statistics are yet available, anecdotal evidence indicates that — as the National Association of School Psychologists predicted — the pandemic has sparked a substantial escalation in behavioral problems inside the nation’s schools.

Through the $122 billion infusion of federal support for public education in the American Rescue Plan, Congress provided an opportunity for education agencies and their community partners to address those challenges. Indeed, as The Sentencing Project documented in its 2021 Back-to-School Action Guide, these Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) dollars — if spent wisely — could help create a new normal in public education that supports student well-being, narrows achievement gaps and closes the school-to-prison pipeline.

But while local education agencies, which receive 90 percent of the ESSER dollars, and states are making encouraging investments in a host of promising strategies with proven power to boost achievement, promote student mental health, improve school climate and minimize disciplinary incidents, far less attention is being paid to reversing problematic practices around school safety and discipline.

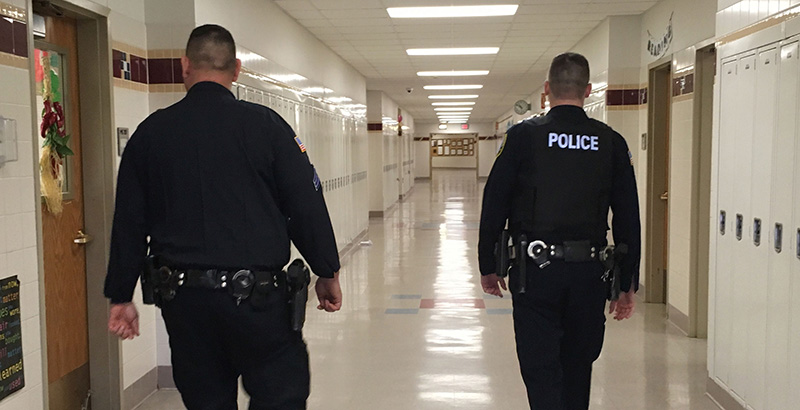

A recent analysis of state plans by The Sentencing Project finds that — despite evidence that an arrest during adolescence sharply decreases the likelihood of high school completion and increases the odds of future arrests and justice system involvement — not a single state is using ESSER funds to end or curtail the criminalization of routine adolescent behavior at school. No states are using the federal money to reduce the presence of police inside schools, although police in the schools are associated with lower academic achievement and don’t improve safety. And none of the state plans mention a goal of reducing arrests at school.

Plans from 11 states and the District of Columbia did outline significant new multi-pronged efforts to reduce the number of students suspended or expelled from school. Michigan has created a school discipline toolkit, for instance, and revised its model code of conduct to reduce suspensions and expand the use of alternative strategies. Indiana is requiring all districts to report how they will reduce the use of exclusionary discipline. Louisiana will provide intensive training and support for school districts with high suspension rates, while Montana will conduct data analysis to identify disproportionate use of exclusionary discipline and then offer training to help districts address discipline disparities. (The Sentencing Project described these and other innovative efforts in this update.)

Five other states will require local education agencies to detail their plans for reducing exclusionary discipline, and 14 more states expressed support for reducing exclusionary discipline but made no commitment to fund or require action toward that goal.

However, despite the widespread use of suspensions (11 million school days lost each year) and evidence that suspensions and expulsions damage students’ futures, exacerbate racial and ethnic disparities, and do nothing to improve school safety or academic achievement, 21 states said little about or did not mention reducing these exclusionary discipline practices in their ESSER spending plans.

Likewise, only Illinois and the District of Columbia described plans to improve responses to truancy, even though punishing young people for attendance problems — and even taking them to court — slows academic progress and harms students’ long-term success. (Research consistently shows that partnering with students and families to identify the root causes of attendance problems is far more effective.) And despite glaring weaknesses in juvenile correctional education, only five states and the District of Columbia proposed concrete strategies in their ESSER plans to better meet the educational needs of youth involved with the justice system.

This lack of action to close the school to prison pipeline limits the impact of new investments to boost student success. Adolescence will always be a time of pushing limits, testing authority and breaking rules. Schools will always face behavioral incidents, and they therefore require effective responses to misbehavior that foster personal growth and protect safety without pushing young people out of school and into the justice system.

With tens of billions in ESSER funds still available and two more years to spend them, ample time remains both to reverse counterproductive discipline strategies and expand on encouraging new investments to boost student success. They are two sides of the same coin.

Richard Mendel is a senior research fellow at The Sentencing Project.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)