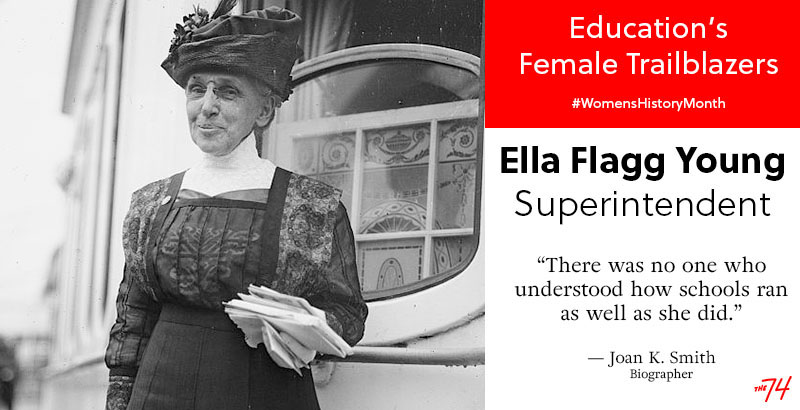

Meet Ella Flagg Young, First Female School Superintendent of a Major U.S. City — and Ed Reform’s Forgotten Thought Leader

March is National Women’s History Month. In recognition, The 74 is sharing stories of remarkable women who transformed U.S. education.

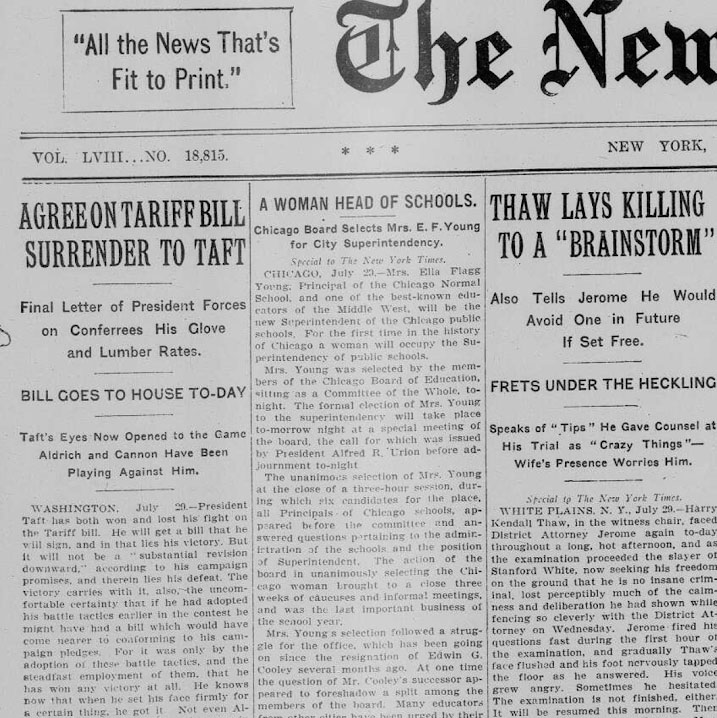

On July 30, 1909, The New York Times’s front page included stories about President William Howard Taft’s tariff bill and a storm that interrupted a Wright Brothers flight. But squished between these two articles was another, just as newsworthy, headline: “A Woman Head of Schools.” It was a story from Chicago, about the first woman selected as superintendent of the city’s school district.

That woman was Ella Flagg Young, and she was the first female superintendent not only of Chicago, but of any major urban public school district in the nation. A progressive education reformer even by today’s standards, Young broke glass ceilings for women in education, advocated for student and teacher voices, and inspired the works of education philosopher John Dewey — before she herself became lost to history.

“One of the tragedies of her story is that a lot of her impacts have either been destroyed in some ways or other people have been given credit for her work,” said Jackie Blount, a professor at Ohio State University who is working on a book about Young. “I want people to know about her.”

Born in 1845 in Buffalo, New York, Young was deemed by her mother to be too fragile to attend school, so she taught herself to read by listening to adults read newspapers aloud, memorizing what they said, and matching their words to the text. She entered grammar school at age 11, and soon after her family relocated to Chicago, she took a teachers examination and passed. But she was only 15, too young to receive a teaching certificate, so she enrolled in a teacher training program.

Her mother thought she wouldn’t be good at teaching children, so Young invented a sort of teacher training regimen for herself, observing classroom teachers at their schools once a week during her last year to see if she could learn.

She graduated in 1862 and started teaching — and a few years later, when Chicago started its first teacher training laboratory school, she was asked to help lead it.

Young worked in virtually every aspect of public education, from teacher to principal to teacher trainer to superintendent to school board member. She even earned her doctorate, something many male superintendents didn’t have. At the time she got her Ph.D. from the University of Chicago, in 1900, only about 5 percent of doctorates nationwide were conferred on women.

For someone so studious, though, Young had an amazing and often unexpected sense of humor, Blount said. She was a great speaker, charismatic. But beneath the surface, Young struggled with the grief of having lost all her family and her husband before she was 30 years old, which may have contributed to the dedication with which she devoted herself to education.

“There was no one who understood how schools ran as well as she did,” said Joan K. Smith, professor emerita at the University of Oklahoma.

Still, when Young interviewed for the superintendent job in 1909, at age 64, her gender was a hurdle for the school board. In Ella Flagg Young: Portrait of a Leader, Smith detailed the challenges. “Two board members said they knew Mrs. Young was qualified but doubted her ‘strength’ for such a position. One of them said, ‘I only wish Mrs. Young were a man,’ ” Smith wrote. “Another said he did not favor giving the job to a woman ‘because they are almost invariably influenced by sentiment rather than cold judgment.’ ”

At the time, women were surging into teaching jobs while men shifted toward administrator positions. (Not much has changed: A century after Young got the superintendent job, about 13 percent of U.S. districts are led by women, even though 72 percent of educators are female, according to the School Superintendents Association, and a recent study found that 82 percent of female superintendents felt their male-dominated school boards did not see them as strong managers and 76 percent felt they weren’t viewed as capable of handling the district’s money.)

So how did she do it? Faced with 27 candidates for superintendent, the 1909 Chicago School Board couldn’t agree on anyone but Young, who was unanimously selected in a second-round vote. The buzz of reporters in the hallway after her interview was so great that Young eventually told them she was more interested in supper than the superintendency, Smith wrote.

Young’s vision of education was very different from the prevailing view at the time — and from many modern-day standards. As a principal and as superintendent, she advocated for increased teacher voice and instituted teacher councils, which had influence over decisions made by school administrators. She pushed for teachers to have higher wages and greater control over their curriculum design.

She even became the first female president of the National Education Association — in 1910, when she was superintendent.

“It is very rare, I think, that one finds a woman who will do as much for other women as Mrs. Young did for her teachers,” one teacher said of Young when she was still a principal.

Young was also a proponent of what today might be called character education and student-driven learning: “our being’s end and aim is the evolution of a character which, through thinking of the right and acting for the right, shall make for right conduct, rectitude, righteousness,” Young wrote. She was also a discipline reformer, cautioning against teachers who were too focused on obedience and punishment and less concerned with supporting individual student growth.

A pragmatist, Young believed that any student, regardless of ability, should be able to learn. She wasn’t a fan of dividing students into grades as much as she was of teachers building relationships with children to tailor their instruction. She wrote a book called Isolation in the Schools, bemoaning a lack of collaboration among teachers, administrators, and students.

But Young’s innovations met resistance from a male-dominated, centralized administrative culture that sought standardization and more control over the schools. It was a turbulent time for Chicago schools already, as the city saw an influx of immigrants that boosted the student population. But the tension between the way she and the board thought the schools should be run eventually drove her out of the superintendency after six years, Blount said, and into retirement before she died of pneumonia three years later, in 1918.

The impact of Young’s 50-plus years in education can still be felt in 2018. Young studied with education philosopher John Dewey during her time at the University of Chicago, and her vast experience as an educator inspired his thinking about schooling and pedagogy.

In fact, Smith first encountered Young as a footnote in Dewey’s work.

“I was constantly getting ideas from her,” he wrote. “More times than I could well say, I didn’t see the meaning or force of some favorite conception of my own till Mrs. Young had given it back to me.”

His daughter, Jane Dewey, added that Young was one of the wisest people Dewey had ever met and that her practical experience helped form his ideas about democracy in schools. Dewey would go on to write Democracy and Education, which emphasized that education is necessary for an informed citizenry and healthy governance. He also supported character development and student-driven learning and inquiry, as Young did.

Even today, the public education system could learn something from Young’s vision, Blount said.

“A lot of people think there’s a sort of inevitability that schools have to be driven by standardization and centralized power,” she said. “In fact, Ella Flagg Young’s story proves that a really large, complicated system can also work really well if there’s an entirely different kind of leadership that values unique contributions of every single member and creativity and intelligence and people working together in community because they want to rather than because they have to.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)