Curriculum Case Study: How a Mid-Pandemic Shift to High-Quality, Evidence-Based Literacy Curriculum Helped Not Just Students — But Teachers, Too

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This is the third in a series of four essays that reflect on a Knowledge Matters Campaign tour of school districts across Massachusetts. Part of a larger set of stories detailing the journey of educators across the country that have embraced a new vision of teaching and learning through implementation of high-quality instructional materials, this piece tells the story of a shift away from one of the most popular reading programs on the market today, Units of Study, and why Salem Public Schools felt the move was vital to meeting the needs of all its students. Follow the rest of our series and previous curriculum case studies here.

“So, when are you going to transition grades 3-5 to the new literacy materials; my teacher friends are asking? They’re so ready!”

I was reminded of this comment by a classroom teacher, which occured when I joined a second-grade common planning meeting earlier this fall, as I listened to what our teachers were telling recent visitors as part of the Knowledge Matters School Tour visit to our district. The excitement among the K-2 team was spreading and 3-5 wanted in on it.

In 2019, our district undertook a review of our early literacy curriculum and instructional model, which we acknowledged was simply not meeting the diverse needs of our students. While academic achievement had improved modestly, far too many students were still not reading on grade level, something that weighed heavily on everyone in the district.

The review revealed many pain points beyond test results — a lack of alignment to standards, teachers feeling overwhelmed by cross checking between materials to ensure we were covering things, and a failure to build knowledge and skills in a systematic, sequential fashion. It also revealed that we’d not provided our staff with the training they needed to build their capacity and confidence to expertly teach foundational literacy skills.

“We were grabbing things from 125 different places, from any place, covering things not spelled out in the Units of Study curriculum,” second grade teacher Stacey Vaillancourt said. “And it was so subjective. What one teacher was reading was not what another one was; there was no consistency.”

Maybe most importantly, we came to realize that our curriculum didn’t hold interest for many of our students. Too often texts emphasized Eurocentric characters and perspectives at the exclusion of providing a balance of windows and mirrors that connected knowledge to the lived experiences of all students. And because our old curriculum, Units of Study, was organized around text and writing genres as opposed to topics or themes, the scope and sequence made it difficult to cohesively build students’ background knowledge and vocabulary in a thoughtful and meaningful way, knowledge that all of our students need.

To further complicate things, a third-party review conducted by Johns Hopkins University of the texts being used in our classrooms revealed that students were being exposed to a steady diet of texts that lacked the depth and complexity expected for the grade level.

Motivated by these growing concerns, early in 2019, a team of 25 classroom teachers, special educators, multilingual teachers, and school and district leaders dug into student performance and growth data, consulted the research, and examined available reviews from EdReports. While the process was slowed slightly by the pandemic, our team emerged with a set of criteria through which prospective materials were considered, and ultimately, Salem Public Schools landed on an evidence-based curriculum resource that all K-2 classrooms began implementing this school year.

Moving a whole district to a new curriculum is a huge undertaking at any time, and certainly so following a school year disrupted by a pandemic and school closures.

“We are sending a message of grace, flexibility, and patience with this,” assistant principal Lauren Weaver said.

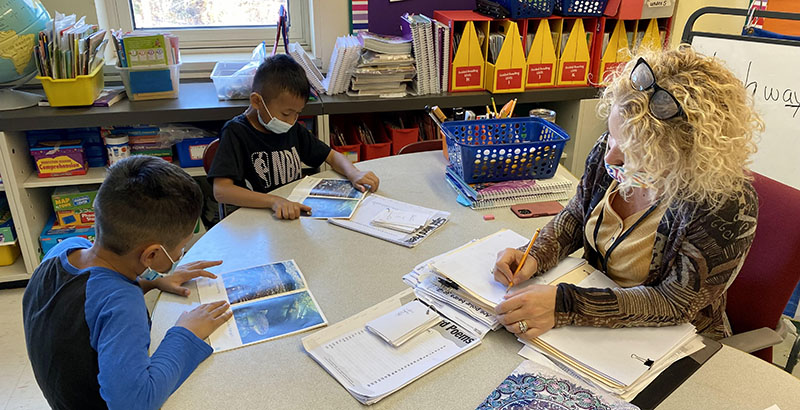

When visiting the second-grade common planning time session, I was prepared to be confronted by some level of frustration and dissent related to the new materials. What I experienced instead was a group of educators thoroughly immersed in learning how to integrate the materials into their practice, which included collaborative problem-solving around parts that did not yet make complete sense to them. I was so encouraged by the level to which the teachers were embracing the materials, and quite pleasantly surprised by the inquiry about when the district might consider including the upper elementary grades in the implementation.

While the pivot to new, high-quality curriculum was unquestionably a student-centered move, we are learning now that there are significant benefits for teachers as well. Resoundingly, teachers point to the enormous weight of planning that has been lifted off their shoulders.

“Teachers want to do best by students; that’s their desire. But planning countless hours makes it difficult,” literacy coach Julie Lenocker said.

Access to these resources is proving transformative for teachers. They no longer need to spend hours building lesson trajectories. Instead, teachers have a clearly defined roadmap of lessons and standards to work from. The new resource provides a clear scope and sequence for reading and writing lessons supported by diverse text sets to use both with the whole class and small groups. Teachers’ time is now spent collaborating with colleagues on how best to implement the new resources to meet the unique needs of the students in front of them which includes reviewing student work and formative assessment data.

The time teachers used to spend searching for mentor texts, read-alouds and book sets for small group instruction, they now use to preview the culturally relevant texts that come with the materials and for planning access and entry points so that all students can fully engage with these high-quality, grade-level texts.

Going forward, we are targeting our professional learning for teachers, reading specialists, and school leaders on strategies that specifically support the implementation of our high-quality curriculum materials. Currently, we have 70 educators from across six elementary schools attending a graduate level course on the science of reading. This districtwide effort was launched to bolster knowledge of research-based literacy practices and will codify approaches used to explicitly teach students how to read.

In Salem Public Schools, we believe it is our moral obligation to ensure that all students have access to high-quality, evidence-based instructional materials. Who knew that the shift would come with many benefits for teachers, as well, by giving back valuable time they can use for planning to teach as opposed to gathering materials they need to teach.

Kate Carbone is deputy superintendent of Salem Public Schools.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)