Lessons From a Global Reckoning: With Coronavirus and a Racial Justice Movement Raging in Texas, Educators Say State’s Curriculum Needs Overhaul

Updated July 16 | This piece is the first in a six-part series, “Lessons from a Global Reckoning,” in which The 74 examines how issues of race are taught — or ignored — in American classrooms. As the pandemic continues through summer protests across the country after the death of George Floyd, this series seeks to take a hard look at how educators are tackling these painful but important topics. Read the rest of the pieces as they are published next week here.

(San Antonio) — Every year, thousands of Texas fifth-graders read from a textbook that tells them they and their families are “illegal immigrants” here to take jobs from classmates.

Students are also asked to consider how supply and demand made slavery necessary throughout the antebellum South.

These and other examples from Texas textbooks and state curriculum standards have been criticized for years.

Now, amid the global pandemic and racial reckonings of the summer, educators are concerned that, whether or not they return to class in person in the next few weeks, students will find most social studies and language arts lessons more problematic and less relatable than ever.

“Distance learning proved that student identity, community and human connection are essential for schooling in 2020,” said Jennifer Rosas, an assistant principal in San Antonio Independent School District, alluding to the scores of students who struggled to stay engaged during spring’s school closures. “Now more than ever, let’s let our history, yes Black and Brown history, guide how we teach and how they learn.”

Textbooks used by districts across Texas have long been called out as biased and politicized, with events often presented from a white, conservative viewpoint, Rosas and other educators said.

A survey of current textbooks yielded examples such as:

These texts, of course, don’t write themselves. Savvas Learning, the publisher, did not respond to a request for comment.

Texas’s curriculum is governed by the State Board of Education, whose 15 members are regionally elected by voters. All 10 current Republican members of the State Board of Education are white, and all five Democratic members are people of color.

The heavily Republican board has, for decades, kept conservative beliefs ensconced in public school classrooms.

The battle over whether to make room for creationism in science curriculum continued until 2014. The political fight was the subject of a 2013 documentary, The Revisionaries.

Sex education, which is currently under review by the board, is mostly nonexistent, except for requirements that abstinence be taught as “the only method that is 100 percent effective in preventing pregnancy, STDs, and the sexual transmission of HIV or acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and the emotional trauma associated with adolescent sexual activity.”

There’s work to be done, conceded Republican State Board of Education Chair Keven Ellis, but there has also been progress.

In the 1980s and ’90s, he said, states across the nation started correcting historical inaccuracies in curriculum, such as previous teaching that kidnapped Africans were better off as slaves. Many of these inaccurate standards were adopted in the 1920s as the families of the last generation of Civil War veterans were, he said, “trying to protect their legacy.”

In 2018, the board revised fifth- and eighth-grade history standards to reflect the expansion of slavery as the primary cause of the Civil War. It had previously been listed third, behind states’ rights and sectionalism. The board also removed Stonewall Jackson as an exemplar of “effective leadership.” The fifth-grade standards online do not yet reflect the latest revision.

The adoption of a Mexican American Studies elective and forthcoming African American studies elective also showed progress, Ellis said: “It’s important for students to see themselves in the material they’re studying.”

Fellow board member Marisa Pérez-Díaz, a Democrat, says that progress was hard won. She advocated for the ethnic studies courses and recalls being told by her Republican colleagues that the courses were “a big ask.”

Some now have bigger changes in mind.

Spurred by the deaths of Black Americans including George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Elijah McClain, a group of Texas public school alumni have started a petition for the State Board of Education to revisit state teaching standards for core courses.

“We’ve seen over the past few weeks that major corporations and government officials rose to the opportunity to do their part in dismantling systemic racism,” Ankita Ajith, one of the four authors of the petition, wrote to The 74. “It’s time for the Texas SBOE to do the same.”

The standards, known as the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS (pronounced by Texans as “TEEKS”), downplay the lasting effects of racism, the petition charges. It points specifically to the absence of events like the Tulsa Massacre and policies like the race-based redlining of neighborhoods during and after the New Deal. Where significant events and people in black history are included, the petition claims, “vague language leaves too much room for individual teachers to teach to their personal biases.”

The standards, known as the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills, or TEKS (pronounced by Texans as “TEEKS”), downplay the lasting effects of racism, the petition charges. It points specifically to the absence of events like the Tulsa Massacre and policies like the race-based redlining of neighborhoods during and after the New Deal. Where significant events and people in black history are included, the petition claims, “vague language leaves too much room for individual teachers to teach to their personal biases.”

In San Antonio, advocates of ethnic studies agree.

“If you really want to get to the root of the issue, it’s the TEKS,” said Lilliana Saldaña, co-director of the Mexican American Studies Academy at the University of Texas at San Antonio. “The standards center whiteness and a settlers’ and colonial narrative.”

Even when presenting the devastation of conquest, slavery and land seizure, she said, the heroism of settlers and colonists is preserved through “the use of language that sanitizes the effects of colonialism.”

Personal politics

“The TEKS are very shallow,” Pérez-Díaz said; they reflect political compromise, not academic consensus or scientific rigor. Because of the composition of the board, Pérez-Díaz said, racial realities are framed as political positions — students are asked to consider “both sides” or “positive and negative effects” of slavery and land seizure from Mexicans and Native Americans.

One assignment in the fourth-grade textbook We Are Texas suggests that Confederate soldiers in the Civil War were fighting “to preserve their way of life,” staying silent on the indefensibility of slavery. It compares their cause to that of Native Americans who did not want to give up their tribal lands to western settlers.

On the other hand, some things are not up for debate in the TEKS, Pérez-Díaz said. Students learn a lot about patriotism and being a good citizen, she explained, but texts portray protestors as radicals.

From kindergarten onward, state standards require teachers to explain the principles of capitalism and the benefits of “free enterprise” in the context of local, state and American history.

Talking only about the benefits of free enterprise minimizes the harm done to Mexican ranchers and agricultural workers, indigenous groups, and enslaved people, Saldaña said.

One fifth-grade standard reads: “Evaluate the effects of supply and demand on business, industry, and agriculture, including the plantation system, in the United States.”

Such equivocation on the realities of slavery has led to repeated controversy as teachers assign students to consider the “balanced view of life as a slave” and textbooks describe enslaved Africans as immigrant workers.

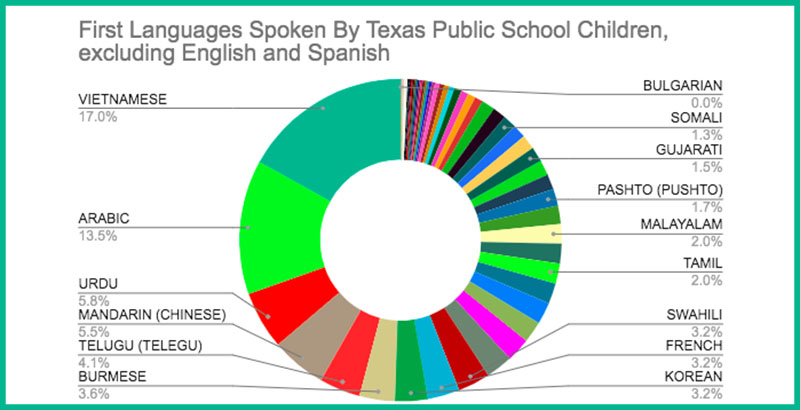

Actual immigration, which affects more than 1 million Texas school children, is also presented solely as a primarily political and economic issue.

One fifth-grade standard reads, “Analyze the effects of exploration, immigration, migration, and limited resources on the economic development and growth of the United States.”

Two portions of the textbook Building Our Nation reference the standard when discussing immigration, and both passages point out that Americans had good reason to fear for their jobs with the influx of immigrant labor.

More than reading a rainbow

When revisiting the standards in 2018, the state used “diverse perspectives” as one of its criteria for determining the characters and historic figures students should study.

César Chávez and Malcolm X are presented as an afterthought, without elaborating on their views on economic, legal and education systems that favored white people, Rosas said.

“They never really tell you [what] they are pushing against.”

HIgh school electives in ethnic studies do address these issues.

Diversifying curriculum, requiring that more people of color and different cultures be represented in textbooks, is not enough, Saldaña said. “We need to be more explicit.”

This has as much to do with how teachers teach as with what they teach, she explained. The teacher has to value students’ perspectives on historical and current events.

“That’s when your students start to be engaged,” Saldaña said. “It’s also about how you relate to your student. [Culturally responsive teaching] cultivates relationships based on trust and on solidarity.”

“That’s when your students start to be engaged,” Saldaña said. “It’s also about how you relate to your student. [Culturally responsive teaching] cultivates relationships based on trust and on solidarity.”

In their vagueness, she said, the TEKS do leave room for this kind of teaching, but teachers need additional tools and training. Through the University of Texas at San Antonio’s MAS Academy, Saldaña and her colleagues offer a more complete view of Texas and American history so that teachers will be able to address state-required skills and knowledge in a way that keeps their students, the majority of whom are non-white, at the center of the story.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)