Kaufman: Does Your Child’s School Use a Strong Curriculum? Why You Should Care, How to Find Out — and What to Do About It

When COVID-19 struck last spring, I was grateful that my kids’ public school was able to get remote learning up and running quickly. My 14-year-old son fell into his distance learning schedule fairly seamlessly. But, like many parents of younger children, I spent several hours each week with my 10-year-old, sorting through school emails and two online learning platforms to figure out where her assignments were and help her complete them. Though I’ve spent many years as an education researcher, I also learned that my fifth-grade math skills are subpar, at best.

This school year, my kids are attending remote school again for the next three months and probably longer. The stakes of online learning feel bigger now, and so do my concerns. Still, there are steps all parents can take to keep their kids’ education on track.

Research already warns that students going back to school this fall have likely retained only about 70 percent of the gains in reading they would have made in a typical school year and only 50 percent of what they learned in math. McKinsey and Co. estimated an average learning loss of seven months for students who do not return to in-person schooling until January, with more months of loss for students from vulnerable groups.

My own education research compounds my worries about online learning. In spring 2019 and spring 2020, my team and I surveyed educators across the nation through RAND’s American Educator Panel. Three of our findings on teachers’ curriculum use that have troubling implications for schools going online in the weeks to come:

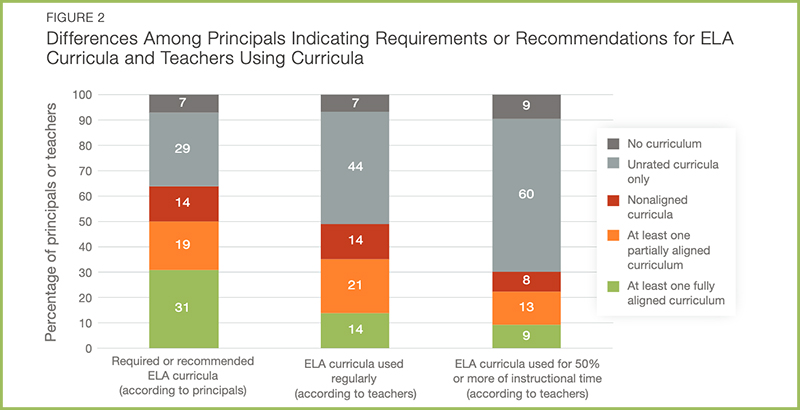

- The majority of U.S. school systems have not adopted strong curriculum. If teachers are going to help students learn the academic standards that are in place in their state, they need good curricula with lessons that closely match up with the content in those standards. But we know from our surveys that most schools in the U.S. pre-pandemic had not adopted curricula aligned with state standards for mathematics and English language arts.

- Most teachers do not consistently use the curricula their district or school had adopted. Less than 30 percent of the teachers we surveyed reported using a single published curriculum as written. The other 70 percent either mostly relied on instructional materials they created themselves, modified more than half of the curriculum materials they used, or cobbled together multiple curricula.

- Among teachers providing remote instruction in the spring, the vast majority did not teach their school’s curriculum. Only 12 percent of teachers we surveyed in late spring reported covering all or nearly all the curriculum they would have covered if school buildings had remained open, and about 1 in 5 teachers reported that what they taught was “all or almost all review.”

Taken together, these findings suggest that K-12 students getting remote instruction this year will not receive the curriculum they need to master or even be exposed to the academic standards they are expected to meet for their grade level. We know schools will try many different hybrid and remote learning models this year that were not options in the spring. We know that a completely remote model will maximize safety but will likely not maximize learning. To add to the challenge, many of the digital learning materials teachers may rely on this school year do not constitute curricula and may be geared mostly toward students practicing learned concepts.

So what can you do to ensure your child is being exposed to standards-aligned, rigorous learning opportunities this year? The first thing is to find out whether your child’s school has adopted strong, standards-aligned curricula. Most textbooks claim alignment, so parents and educators need evidence that curricula are standards-aligned from a third party. Some states, including Louisiana, Tennessee and Nebraska, provide reviews of which curricula are aligned with their academic standards. If your state doesn’t provide reviews, you might take a look at ratings from EdReports, an independent organization that reviews the curricula alignment with evidence from reading, science, and college- and career-ready standards.

Second, regardless of what curriculum the school is using, investigate whether your child is learning new concepts addressed by your state standards. If your child is doing a lot of what looks like rote practice without grappling with new concepts, or keeps making the same mistakes and isn’t getting the input needed to improve, you may need to talk with the teacher or principal to better understand the curriculum. You can ask how the school is providing students with the kind of instruction that will build on last year’s knowledge and help them learn new things.

Finally, remind yourself — as I keep doing — that if your children are getting high-quality, standards-aligned instruction, they will likely struggle at least somewhat with the content. They will need support from you and their teachers. And, like me, you may be concerned you won’t have the time to provide that support. If you are overwhelmed, consider asking schools about possibilities for one-to-one tutors or others who can help. This is a good time to pull together, and there are likely many ways that we all can address children’s learning needs at this critical and chaotic time.

Julia Kaufman is a senior policy researcher at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)