K-12 at Gallaudet: Schools Beloved by Deaf Students Defy National Trend Away from Specialized Education

Washington, D.C. (Updated June 27)

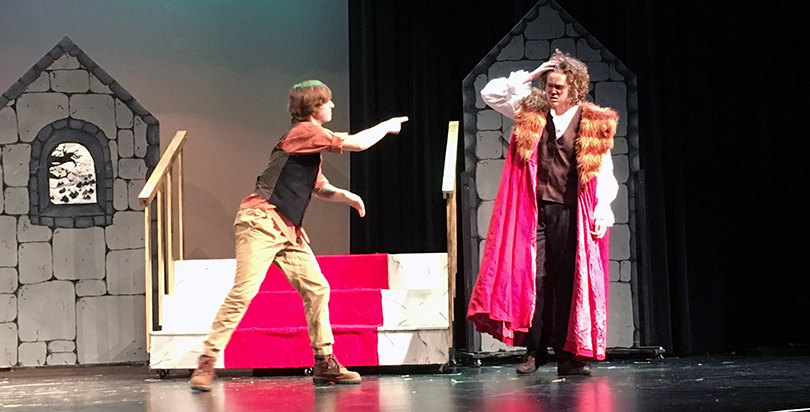

At the Model Secondary School for the Deaf’s April production of the Disney classic, that language is American Sign Language. There’s no singing, but otherwise this version — with voice actors for those in the audience who aren’t fluent in ASL — is like every other performed in high schools across the country, acted with a lot of heart if not a lot of skill.

The Model Secondary School (better known by its acronym, MSSD) and its sister school, the Kendall Demonstration Elementary School that serves children from infancy through eighth grade, are two specialized schools that educate deaf and hard-of-hearing children. Though they reach a specialized student body, in many ways, they’re exactly like every other school in the country.

One key difference: They are both housed on the 99-acre grounds of Gallaudet University, the only liberal arts college for the deaf in the world, which started in 1864. Elementary and secondary schools have existed under the umbrella of Gallaudet, previously known as the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb and Blind, since its creation. They are chartered under a federal law, the Education for the Deaf Act, and report to the U.S. Department of Education. An accompanying research institute, the Laurent Clerc Deaf Education Center, is a hub for information on deaf education for the whole country.

The schools aim to be a beacon of educational best practices for deaf students across the country. Yet despite the essential service they provide to their own deaf students and those across the nation, enrollment is down in recent years, pitting the institutions of Kendall and MSSD against the 40-year-old national edict to educate children with disabilities in mainstream classes whenever possible.

It takes a second to realize why the wagon used to tote the preschoolers enrolled at Kendall, a sprawling building in D.C.’s northeast quadrant, is a little different. Rather than traditional benches where students sit in pairs facing forward, the just-purchased green plastic wagon arranges students facing each other. That lets them continue to communicate, using sign language, when they’re outside the building, be it for a field trip or emergency evacuation.

Otherwise, little seems out of the ordinary. The preschool rooms have books and toy kitchens and a pet bird and some goldfish. There’s a gym and a cafeteria and anti-bullying posters. Ahead of an early dismissal on a recent Friday, the school was holding an assembly to congratulate two students for winning a national contest.

It’s the small details at Kendall, like that plastic wagon, that hint at its distinct student population.

The fancy flat screen TVs on the wall, for example, aren’t just a way to blow grant money — for students and staff who can’t hear, they function as the public address and emergency alert system. Glenn Lockhart, the head of public relations and communications at the Clerc Center and a Kendall alum, explains all this through an interpreter.

Circular, rather than rectangular, tables in the lunchroom also facilitate conversation in ASL, and one is specifically designated for students who want to practice speaking. The wall-sized family events calendar offers twice-weekly ASL classes for families (broadly defined as aunts and uncles, neighbors, or really anyone else who wants to communicate with a deaf student, Lockhart says.)

And that national contest the Kendall students won? Best friends and fellow fourth-graders Savannah Brown and Hiruni Hewapathirana, made the winning videos about what they want to be when they grow up (the president and a heart surgeon, respectively). Their prize, sponsored by video conferencing company Convo, was a trip to Los Angeles to see Nyle DiMarco. DiMarco, the only deaf contestant and a past winner of “America’s Next Top Model,” was competing on “Dancing with the Stars” — which he also went on to win. (The whole school has gone crazy for DWTS since DiMarco joined the cast, Lockhart said.)

The girls showed their classmates a slideshow of photos, including one of them pretending to hold the iconic Hollywood sign and another with deaf actress Marlee Matlin’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. They were nervous about going to the television taping: Savannah had “about a thousand bats” in her stomach, she said in a video shown after the girls’ presentation. But they were thrilled with DiMarco’s performance — he was dressed as Jim Carrey’s character from “The Mask”, green face and all.

Services at Kendall can begin at birth, and any child who lives in the “national capitol region” (Washington, D.C. and adjacent counties in Maryland and Virginia) can attend, tuition-free. The school, which had 106 students in its September 2015 enrollment count, is funded through the federal government. Last year, Gallaudet received a little over $121 million total, for both the pre-K-8 and 9-12 schools, the Clerc Center and some college programs.

About 2 to 3 children per 1,000 are born with some level of hearing loss in one or both ears, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

It’s vital that babies start learning a language, even if it isn’t a verbal one, as early as possible because increasing amounts of research show that language is essential to the development of other brain functions, and to improved psychological and social outcomes. Deaf babies who are identified and receive early intervention services before their first birthday have language skills almost equivalent to their hearing peers by age 5.

Norma Morán and Franklin Torres' two children, Ramón and Teófilo, are enrolled in the school’s early childhood programs. Both parents already worked for Gallaudet when their children were born, so it was a natural fit to enroll them at Kendall, Morán said via email.

Ramón, who is enrolled in the class for one-year-olds, loves seeing and interacting with his peers and is “thriving” in the program, Moran said. Her favorite thing about the school is the level of parental involvement. “We are considered as a valued, contributing, and vital part of the school’s excellency,” she added.

There used to be myths that if deaf babies learned ASL they wouldn’t, or couldn’t, learn to speak or learn written English, said Susan Jacoby, executive director of planning, development and dissemination at the Clerc Center, which shares research to debunk those ideas.

“There’s only positive outcomes that come from having access to language because it gives you constant access to information, the same as hearing babies,” she said. “What we have now is a renaissance of research that really helps us demonstrate and show that the myths out there are inaccurate.”

Infants at Kendall attend for three hours, twice a week, with their parents. Beginning at age 2, the students attend all day, every day.

Older children are taught a curriculum that’s aligned to the Common Core State Standards, and they take the same assessments being used in Maryland, currently the PARCC exam.

The Education of the Deaf Act, first passed in 1986 and amended several times since, requires the school to align their work to the curriculum and assessments used by whatever state they choose.

All the students who attend have the individualized education plans they’re entitled to under federal law. Very few, less than 15 percent of the total enrollment, have cochlear implants, an electronic device that allows sounds to bypass nonfunctional portions of the ear and go directly to nerves that connect to the brain. Some advocates in the deaf community oppose the use of implants because they imply that deafness is a condition that needs to be cured or fixed. Similarly, some parents have requested that their children learn to speak in addition to learning ASL, but that’s far from universal.

Jesse Saunders looked at other schools but chose to send his daughters, Chloe, a kindergartener, and Talia, a fourth-grader, to Kendall. The school is diverse, and the girls particularly like the afterschool programs, which offer options like rollerblading, parkour and swimming. Saunders likes the close-knit community of families that help — rather than compete with — one another.

Ultimately, he said, it’s about the location.

“Kendall is on the campus of the world’s only deaf university, which means there are many opportunities for Kendall students to meet strong deaf role models from Gallaudet and the world,” he added.

Model, meanwhile, is a 9th to 12th grade boarding school and accepts any U.S. citizen. It, too, straddles the line between just-like-every-other-school and uniquely special.

In addition to the spring theater production, there’s a fall play and a winter dance show. The school also offers student government, academic bowl, a robotics team, sports teams and other extracurriculars. The sports teams compete both against other deaf schools and other similarly sized, mostly private, mainstream schools in the area.

Every one of MSSD’s 166 students has to complete community service, and the seniors undertake an internship once a week for a semester, volunteering and working in such places as the National Association of the Deaf’s office in nearby Silver Spring, Maryland, with the younger children at Kendall, or in a homeless shelter that provides specialized services for the deaf and hard of hearing.

Travis Wadell, a senior and this year’s homecoming king, moderated a panel at a spring open house for prospective students. He had previously attended a deaf school in Virginia, but it was much smaller, and he was nervous when he came to MSSD for football camp.

Now, though, “if ever I go home, I’m so happy to come back here,” he said through an interpreter at the panel.

The students, who live in dorms (a new one is opening next year), have typical teenage complaints: the food isn’t up to par, and seniors wish they had more freedom.

One of the best things about MSSD, the students said, is its diversity. Many came from very small state schools for the deaf where they had known their peers their entire school careers.

The student body is about 45 percent white, 28 percent black, 18 percent Hispanic and 9 percent Asian, and students come from about 30 states and Puerto Rico. The male-to-female ration is about 50-50. Parents are responsible for a student activity fee and security deposit on the dorm; the school’s federal funding covers tuition and other costs.

Bullying does happen, the student panelists said, but much less often than at the other schools they attended.

“We’re like a family here, and when somebody picks on someone in my family, I step up to stop it,” said Wadell, the homecoming king.

The school “was a blessing for my two kids,” said parent Kathleen Jensen, whose two daughters, a freshman and a senior, are students here. The school has high expectations for its students, and teachers don’t dumb down work just because students are deaf, she said during the open house presentation.

Jensen, like her daughters, is deaf. That isn’t typical. Roughly half of the cases of hearing loss in babies have some sort of genetic component, but that doesn’t mean that all of those children have deaf parents, according to the CDC. (In fact, over 90 percent of all deaf children have two hearing parents). Among babies whose deafness is not genetic, a quarter of cases can be traced to a maternal infection during pregnancy, head trauma, or complications after birth. For the remaining quarter, the cause of deafness is unknown.

The graduation rate at MSSD in 2014 was 72 percent, below the 82 percent national average that same year, but higher than the national average for students with disabilities, which in recent years has been around 60 percent.

Graduates mostly go on to college. Of the 30 graduates of the 45-member class of 2014 who responded to a survey, 15 attended Gallaudet, seven were at the Rochester Institute of Technology’s National Technical Institute for the Deaf, and three at other colleges. Three more said they were working, and two were neither working nor in higher education.

In the past 40 years, special education in the U.S. has evolved from a system where students with disabilities were kept out of mainstream schools, either by law or because schools couldn’t serve them, to one where inclusion in mainstream classrooms is the goal. The entire premise of Kendall, Model and other schools for the deaf is that inclusion is not always the best option for children with disabilities.

That tension shows in enrollment figures.

More than 80 percent of deaf children nationally attended a specialized school before the passage of the law requiring schools to educate children with disabilities, according to statistics from Gallaudet. In its wake, that number has more or less flipped, with greater than 80 percent of deaf and hard-of-hearing children in mainstream schools and the remainder in the 100 or so specialized schools for the deaf across the country. About 78,000 children were deaf or hard of hearing as of the 2011-2012 school year, according to federal data. That number is down from 88,000 in the late 1970s.

And at Kendall, last year’s official enrollment of 106 fell short of its goal of 115, which already was lowered from past years’ targets of 140, according to an annual report the university sends to the federal education department.

The school re-evaluates enrollment goals every five years, and adjusts given the other activities the school undertakes, Lockhart said later via email. The school offers rolling admission, so may hit that target later in the year even if it’s below 115 on the Sept. 15 annual reporting date. School leaders are also expecting to meet or exceed that number for next year, he said, as there are more infants enrolled for the fall than eighth-graders who will be departing.

Advocates for deaf education, though, make clear deaf-only schools aren’t the terrible warehouses advocates were trying to banish when they won passage of the 1975 law that’s now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

The National Association for the Deaf, for example, emphasizes in its official position on K-12 education that a continuum of options should be available to deaf students.

“While the regular classroom in the neighborhood school may be the appropriate placement for some deaf and hard-of-hearing students, for many it is not,” the group wrote.

The best way to think of it, said Flavia Fleischer, chair of the department of deaf studies at California State University Northridge, is whether a child’s education is direct or indirect.

Children who need wheelchairs but have no cognitive disabilities can otherwise participate directly in their learning and most other aspects of their school experience.

“We can’t categorize all disabled people into one large population, and that’s what’s causing a ton of problems,” Fleischer said through an interpreter.

But contrast that child in a wheelchair with a deaf student, said Jacoby of the Clerc Center. Even if he had an ASL translator during class, all of his learning would be indirect through the interpreter. He might not be able to participate in extracurricular activities. At lunch he’d hardly want to discuss crushes or puberty or any of the other myriad anxieties teenagers face if he had to do it through an adult interpreter, or with the perhaps handful of other students who use ASL.

“Students who come here can access everything 100 percent of the time,” she said. “We want that same opportunity for all deaf students.”

In addition to all the work going on to educate students at Kendall and MSSD, the Clerc Center serves as a clearinghouse of information for parents and educators nationally. The Education of the Deaf Act gives the center a special mandate to serve the country, particularly underserved deaf populations — children of color, children of parents whose first language is not English, and those in rural areas.

They offer a popular annual practitioners’ journal, Odyssey. The center also puts out guides for hearing parents who may be dealing with crafting IEPs or obtaining translators for the first time. There’s professional development for teachers, particularly those who may be facing teaching their first deaf student. And although most lessons can be taught to deaf students in the same way, some do require a bit of finesse — the center has, for example, given a seminar in how to teach sex education to deaf teenagers using appropriate ASL.

“We recognize that serving the nation, and taking what we’re doing here and the good work that’s happening elsewhere, requires a multiple-pronged approach,” Jacoby said.

Although the center’s function is purely educational and officials don’t lobby, information they glean from the work at Kendall and MSSD might be used as schools implement legislative changes. The Every Student Succeeds Act, the recent overhaul of the nation’s K-12 education law, for example, places a new emphasis on computerized testing. The testing experience of students at Kendall and MSSD will be shared with PARCC and others as deaf students around the country begin to take more and more computerized exams.

Every deaf child’s experience changes as he or she moves through the education system, and there are new deaf babies being born every day, Jacoby said.

“Our work evolves as education evolves,” she said.

At the same time, center administrators have to consider both families where a deaf baby might be the first deaf person the parent has met, as well as families that have had four or five generations of deaf babies.

“All of those deaf babies should be celebrated and all of those deaf babies have the potential to grow up and accomplish and achieve whatever they aspire to and whatever their life’s trajectory might be and we’re here to provide those resources,” Jacoby said.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)