‘It’s So Hard’: As Trans Bans Spread, Experts Weigh How to Balance Fairness and Inclusion in High School Sports

After germinating largely outside the political limelight over the past few years, a new cultural controversy has come to dominate the early months of the Biden administration: the debate over the rights of transgender youth.

The first push came from the president, who issued an executive order on his first day in office calling for federal agencies to root out discrimination based on gender identity and expression, including in public schools. In February, the administration also ended federal support for litigation filed in Connecticut by a group of high school runners who argue that their rights under Title IX were violated by the state’s policy of allowing trans girls to race against them.

Republicans picked up the gauntlet happily, with lawmakers in 28 states introducing bills to require K-12 athletes to compete in the gender category that they were assigned to at birth. Governors in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee have all signed such laws, which have also passed in at least one chamber of state legislatures in Alabama, Kansas, North Dakota, and Utah. After a split between Republicans in South Dakota, Gov. Kristi Noem has issued a pair of executive orders along the same lines.

Beneath the political stakes lie swiftly changing legal and cultural mores, which are themselves being reshaped by new discoveries on the biology of athletic performance. In all, the status of trans athletes — and particularly the question of whether trans females should be allowed to compete in the girls’ category in high school competitions — has been taken up by combatants on all sides of America’s ongoing debate over the politics of sex and gender. Meanwhile, as the fight moves from playing fields to legislative chambers and courtrooms, advocates are attempting to strike a compromise between the necessities of competitive fairness and inclusion.

That balance has begun to develop at the pinnacle of elite sport, with regulatory bodies like the NCAA and the International Olympic Committee reaching accommodations that allow trans women to participate under specific conditions — typically including measures to suppress their bodies’ production of testosterone, which is linked to performance attributes like speed, power, and endurance. But adolescence, when many trans children are still early in their social and physical transitions, is a far more ambiguous stage.

Joanna Harper, a sports researcher at England’s Loughborough University and herself a trans runner, observed that various proposals to address the issue for teenagers all come with downsides. In an interview, she set a goal of “being as inclusive as we can possibly be without destroying the competitive balance.”

“It’s so hard,” said Harper. “How do you tell a 15- or 16-year old that they have to go on hormone therapy to play sports? It’s an extraordinarily difficult thing to say, but for these very high-performing athletes, it does create a conundrum.”

To others, one consideration supersedes all others: the need to welcome trans children into all aspects of school life, including sports. Melanie Willingham-Jaggers, the executive director of the advocacy group GLSEN (previously known as the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network), said that no claims around competitive fairness could justify treating trans students any different from their cisgender peers (i.e., those whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth).

“To use words from another civil rights fight, we know that anything separate is not equal. We know that when we start differentiating across lines of identity, young people will not be served by that.”

A ‘patchwork’ system

But according to Doriane Lambelet Coleman, sex differentiation is vital to the survival of women’s athletics. A professor at Duke Law School, Coleman is the co-director of the institution’s Center for Sports Law and Policy. She is also a former collegiate track champion who has worked in both American and international settings to develop anti-doping policies and rules determining eligibility for women’s competition.

Coleman has argued that Title IX, which forbids sex-based discrimination across all federally funded educational programs, clearly mandates the segregation of athletes into categories according to sex-linked traits. Since its very purpose is to provide women and girls with the same access to athletic opportunity that boys have always enjoyed, forcing cisgender females to contend with rivals whose bodies lend them a competitive advantage effectively “[defeats] the purposes of the institution that is girls’ sport.”

“We need legislation that affirms the commitment to girl’s and women’s sport, and specifically to this set-aside of separate-sex teams on the basis of biological sex,” Coleman said. “It was never in doubt before that that’s what separate-sex sport meant, but now that it is questioned, we need to re-affirm that commitment.”

But Coleman also rejects the legal barriers being proposed and passed by Republicans, calling them overbroad. Some exceptions need to be drawn for trans girls and women who have undergone hormone treatment, or who transitioned before the onset of male puberty, she added.

The legislative push at the state level began almost exactly a year ago in Idaho, which flatly banned trans females from playing on girls’ teams at K-12 and post-secondary schools. In instances where doubt existed about an athlete’s biological sex, it would be resolved by an examination of “the student’s reproductive anatomy, genetic makeup, or normal endogenously produced testosterone levels,” the text read. (The law was temporarily blocked by a federal judge last summer, and litigation is still pending.)

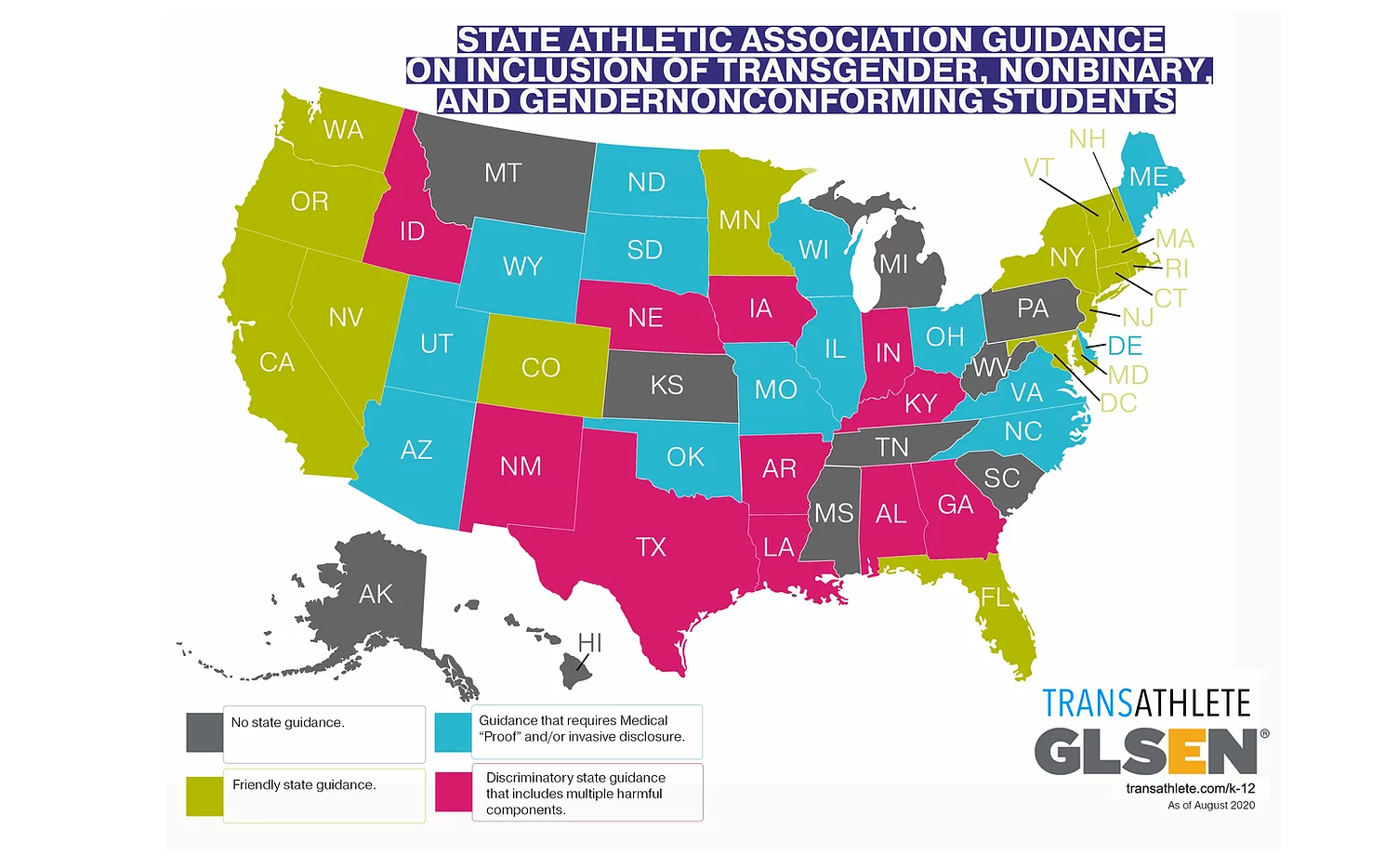

As the legislation moves through statehouses around the country, students are facing an increasingly divided picture of athletic eligibility. According to the online resource Transathlete.com, 16 mostly socially progressive states currently allow trans girls to compete in the category that matches their gender identity. Among the rest, some require they take medically prescribed hormone therapy, some require them to adhere to their natal sex, and some offer no recommendation.

Willingham-Jaggers referred to the sharp differences between different jurisdictions as a “patchwork” system that cries out for national clarification. In her view, that should come through the passage of the Equality Act, a federal bill that would amend existing civil rights law to prohibit discrimination in housing, education, and employment on the basis of gender identity or sexual orientation. The Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives in February, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has already announced that it will be brought to the upper chamber for a vote.

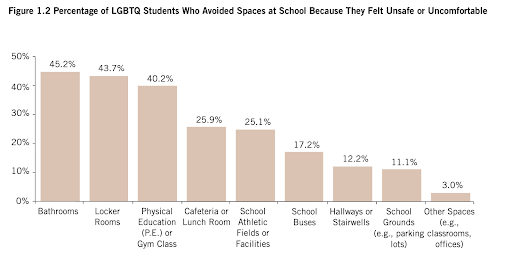

Federal action is warranted because of the anxiety that trans students often feel about athletic participation, Willingham-Jaggers said. According to a 2019 GLSEN survey, over 10 percent of LGBT students feel discouraged from participating in sports because of their gender or sexual orientation. Forty-four percent of respondents said they avoided locker rooms because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable, 40 percent avoided gym or physical education classes, and 25 percent avoided athletic facilities.

“What happens when we discourage or intentionally exclude young people who are non-binary or transgender from sports [is that we] lock them out of all the positive effects that sports have on all young people — cis, trans, or non-binary,” Willingham-Jaggers said. “What is right for all students is also right for trans students.”

‘It’s no longer about sex’

Given the tiny margins Democrats now hold in Congress, neither the Equality Act nor any other federal legislation centered on trans youth looks likely to pass this session. While the possibility of regulatory reform still exists — the Justice Department recently issued a memo stating that LGBT students would be protected under existing civil rights laws that prohibit discrimination based on sex, including Title IX — policymakers and educators still face the question of how the rights of trans and cisgender girls can be reconciled when they come into conflict.

For some experts, hormone therapy is a necessary part of any solution, at least at the most competitive levels of women’s sport. In recognition of changing norms, leading regulatory bodies like the NCAA and International Olympic Committee have created policies that require trans females to undergo estrogen or testosterone-suppression therapy before they can become eligible for women’s events.

Though she condemns the outright bans now under consideration in U.S. legislatures, calling them politically motivated, Loughborough University’s Harper said it was “perfectly reasonable” to place some restrictions on the participation of trans women in competitions.

As evidence, she cited the example of June Eastwood, a University of Montana runner who in 2019 became the first openly trans female to compete in a Division I cross-country meet. Eastwood completed the prescribed course of testosterone suppression during her transition, and generally proved a high-level if unspectacular performer in the women’s division. Had she not undergone the treatment, however, she might have easily dominated her sport; while running in the men’s category, Eastwood’s personal best in the 1500 meters was just a fraction of a second behind the women’s world record.

“Successful trans girls who have gone through male puberty, who have experienced all the gains that gives them and are good at their sport, will simply be too good, too successful in girls’ sports, unless you require them go through hormone therapy,” Harper said.

A less hypothetical case came during the 2016 Olympics, when all three medalists in the women’s 800 meters event were either known or suspected to have a rare genetic condition that produces both X and Y chromosomes in women. With testosterone levels that far exceed that of typical female athletes, those runners are now required to undergo treatment to reduce their testosterone in order to enter women’s events between the quarter-mile and the mile.

But what is possible at elite levels of competition might not be workable in high school. Not all trans children have access to hormone therapies, and requiring them as a prerequisite for athletic participation could inadvertently distort students’ decisions around gender transition. To make things even more complicated, Republican legislators in several states have introduced bans on minors receiving “gender-affirming health care,” a treatment method that can recommend the use of puberty blockers and hormone replacement. In Arkansas, the first state to pass such a ban, Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson issued a veto on Monday only to see it overridden the next day. If other states take the same approach, many transgender youth could be faced with a Catch-22 scenario: needing hormone therapy to compete in sports according to their gender identity, but being prohibited from receiving them.

All of it combines to make high school sports a particularly challenging space to adjudicate.

The best-known conflict within the realm of K-12 sports is now playing out in Connecticut, where three runners have sued the state in federal court for permitting trans athletes to run track against cisgender girls. Between 2017 and 2019, those trans girls, Terry Miller and Andraya Yearwood, combined to claim 15 state championship races. While former Attorney General William Barr formally backed the lawsuit, calling Connecticut’s policies “fundamentally unfair to female athletes,” the Justice Department under President Biden has dropped its support.

In part, the debate hinges on interpretations of Title IX, which was enacted nearly a half-century ago with the express purpose of protecting women from exclusion in educational settings like sports. At the time of its establishment, school districts and universities directed their athletic budgets overwhelmingly toward male sports, and the concept of transgender identity was mostly outside the mainstream. By some estimates, participation in girls’ sport has increased by over 1,000 percent in the decades since. At the same time, the law permits “separate teams for members of each sex where selection for such teams is based upon competitive skill.”

Duke’s Coleman sees the increasing social acceptance of LGBT communities as a positive development, but warns that it likely will also generate more such cases if states like Connecticut don’t carefully insulate the category of cisgender girls. Otherwise, she argued, it could drift into something like an open division freely entered not only by trans girls, but also gender-fluid and nonbinary competitors, and even trans boys who are actively taking testosterone but still permitted to compete against females.

“It’s no longer about sex; it’s not about sex-linked hormones; and it’s not even about gender identity, since trans boys can stay in,” Coleman said. “So I can’t even describe that group anymore. And if you can’t describe that group, who’s going to fund it? And if people continue to fund it, how will it stand legally? It no longer has integrity or a purpose that we can identify because you’ve let everybody in, essentially.”

Culture war fodder

Only a handful of states have so far restricted access to girl’s and women’s sports exclusively to natal females, and all are among the most Republican-leaning in the country. At the national level, Republican Senators Marco Rubio and Mike Lee have both called for similar measures.

David Hopkins, a political scientist at Boston College whose research focuses on U.S. political parties, said that the GOP seems to be coalescing around the proposal out of a recognition that LGBT acceptance remains “a controversial, uncomfortable issue for a lot of voters.”

“Republican politicians, who are increasingly oriented toward cultural as opposed to economic causes, have been looking for ways to translate the culture war into policy and legislation,” he continued. “So much of the culture war is actually not about what the government does, but here’s a case where it can be.”

While public surveys indicate that much of President Biden’s agenda is reasonably popular, the polling also suggests an area of softness around the issue of trans athletes. According to a 2019 poll from Morning Consult, 57 percent of respondents agreed that transgender women possessed an athletic edge over other women. Another, administered last month, found that 53 percent of registered voters supported a ban on trans athletes in women’s sports. Even among Democrats, just 42 percent of respondents said they would oppose such a ban, compared with 40 percent who would support it.

Aside from those figures, state-level Republicans are likely reading signs from former President Donald Trump, who said during his speech at February’s CPAC convention that “women’s sports as we know it [sic] will die” if restrictions aren’t adopted. In the same way that some lawmakers adopted Trump’s hatred of the New York Times’s 1619 Project, and are now moving to ban its associated curriculum from use in public schools, they are now attaching themselves to another highly charged topic whose salience he has recently elevated.

But few if any elected Democrats have vocally opposed allowing trans women and girls to compete in sports according to their gender identity rather than their biological sex. Of the 16 states where official guidance recommends that course, all but one — Florida — has voted for the Democratic candidate in the last four presidential elections. This too reflects the partisan and geographic polarization at work, Hopkins argued.

“You don’t have a faction in the Democratic Party that’s pushing back against that,” he said. “They’re not worrying about carrying Senate races in South Dakota or Arkansas anymore because they’re out of the game in those states. That has really contributed to the culture war polarization between the two parties: Neither party is really trying to compete in the parts of the country that, culturally, are on the other side.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)