‘It Just Becomes Like a Ghost Town’: As Nuclear Plants Close in Record Numbers Across U.S., Small-Town School Districts Brace for Catastrophic Tax Losses

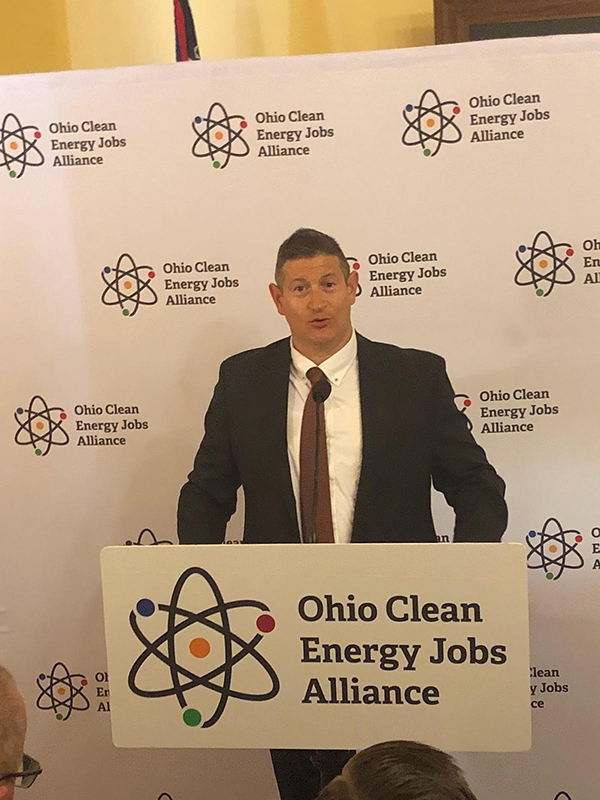

Guy Parmigian, the superintendent of Benton-Carroll-Salem Schools in Ohio, never intended to become an expert on nuclear energy.

A lifelong educator more used to touting his district’s high test scores and low taxes, he is now conversant on the strength of the energy grid and the link between electricity security and economic development.

“I’ve become immersed in it because I have to. I used to take turning on the lights for granted. I don’t anymore,” he said.

Parmigian expanded his expertise after the owners of the district’s largest employer and taxpayer, the Davis-Besse nuclear plant, announced plans to close the plant next year. It’s one of nine plants across the country scheduled to close by 2025, on top of seven that have closed since 2013.

The district is already feeling the pain of an industry in decline: Since 2018, when the plant’s operators received a new tax evaluation that cut 25 percent from the district’s budget, the school system has eliminated several teaching and staff jobs. Just this month, Parmigian announced that a position on his already bare-bones administrative team will go unfilled, adding maintenance supervisor to his list of duties.

More cuts are on the horizon if voters don’t agree Aug. 6 to shoulder a larger share of the cost of school services via higher property taxes.

A failure at the polls would have real consequences for students, officials announced. The district would stop bus service for high school students and for those living within two miles of school. Third-grade swimming lessons would be eliminated, as would an afterschool childcare program. Fees for participating in sports would go up. The band might not go to away football games.

Small school districts always suffer when large employers leave town, but for those home to the country’s 59 nuclear plants, the stakes are higher. Largely owing to competition from cheap natural gas obtained by fracking, up to half the country’s plants could close by 2030, experts warn. And once plants are shuttered, it’s impossible to immediately replace them with new facilities, as the elaborate environmental cleanups required can take between eight and 60 years.

“It’s kind of now like, I don’t want to say the party’s over, but the party’s not what it used to be, and that plant isn’t generating that same revenue that it used to for us,” Parmigian said. “If [residents] want to continue to have a strong school system, they have to pay a little bit more.”

But residents have already rejected three proposed income tax hikes. If passed, the Aug. 6 proposal is expected to raise $1.5 million.

The worst-case scenario, shuttering the plant, would be disastrous for the district, Parmigian said.

“We know that it would be catastrophic for our community. We would lose students. The tax base would be further eroded,” he added.

After months of negotiations, the Ohio House on Tuesday passed a contentious bill to rescue Davis-Besse and Perry, another plant slated for imminent closure, for the next few years. It now heads to Gov. Mike DeWine, who has said he’ll sign it. Under the bill, funds from a new electricity tax will help shore up the company that owns the plants, FirstEnergy Solutions, which is currently in bankruptcy proceedings.

Though the bill staves off disaster for now, Ohio school leaders have been grappling with the industry’s decline for years, a fact of life the bailout won’t change.

Jack Thompson, Perry’s superintendent, went to Columbus to lobby for the bailout. His district has already lost $3 million of its $21 million total budget to tax devaluations. However, unlike taxpayers in Benton-Carroll-Salem, residents in his district have so far been shielded from a tax hike by additional state aid and a declining student population that has necessitated a thinning of the ranks of teachers.

Closing the plant would mean a loss of “a good third of our budget at minimum,” he said. “We’d be boarding up buildings. It would not be pretty.”

Closure would also mean the exodus of roughly 750 employees and their families.

“It just becomes like a ghost town,” Thompson said.

An industry in decline

Closing nuclear plants is nothing new, but the sheer number of sites set to be shuttered in coming years has left a record number of school leaders facing the same worrying fiscal fate as Parmigian and Thompson.

After the heyday of new construction in the 1950s and ’60s, nuclear power plants closed at a pretty steady pace, about seven per decade from the 1960s through the 1990s, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Then came a lull, and no plants closed for over 15 years.

The current wave of closures kicked off with Florida’s Crystal River plant in 2013. The state of the nuclear energy industry is “dire,” Charles Mason, a professor of petroleum and natural gas economics at the University of Wyoming, told The 74.

A report Mason helped prepare for the Obama administration in 2016 predicted that as many as half of the plants in the country could close by 2030 if economic conditions don’t change.

The industry traces its problems back to 2008, said Matthew Wald, a spokesman for the Nuclear Energy Institute, an industry lobbying association. The recession that year dampened some industrial demand for power overall, but the bigger challenge was the development of fracking and the availability of cheaper, more plentiful natural gas.

Industry advocates say shutting the plants risks a key source of stable, high-paying jobs, as well as substantial tax revenue for the typically rural towns where they reside. The average power plant has a $40 million payroll and pays $16 million in state and local taxes, Wald said.

In advocating for bailouts such as the one that just passed in Ohio, industry representatives argue that nuclear power doesn’t produce carbon emissions and so should be subsidized in the same way wind and solar energy are in many places. (Environmental advocates, however, point to the substantial harm to the environment that comes with building nuclear plants and from mining the uranium that powers them.)

But bailout measures don’t change the inherent economic conditions that created the problem, Mason said.

“The plants are struggling to be economically competitive given the current energy market climate, and I don’t know why that changes. I don’t know how there’s going to be a happy ending there,” he said.

When plants close, the impact to local schools varies widely. Districts can cushion the blow when state regulators intercede, as they did in New York when the state opted in 2016 to provide up to $500 million in subsidies, or when plant owners announce closure plans well ahead of time, which gave a district in Southern California time to set up a charitable foundation to shore up finances long before a 2025 closure.

Above all, a broader, more diverse tax base has helped districts stay afloat.

Three Mile Island, the central Pennsylvania nuclear plant that experienced the worst nuclear accident in the country in 1979, is scheduled to close in September. Though a state bailout effort failed, the Lower Dauphin school district has not experienced the same catastrophic effects as Benton-Carroll-Salem.

A $300,000 payment the plant has provided annually to the district after a tax reassessment in the early 2000s will cease in the 2020-21 school year. But even if the district lost its share of the plant’s entire $1 million annual tax haul, that’s a relatively small portion of its overall $63 million budget, said district spokesman Jim Hazen.

Lower Dauphin and other school districts around the country face fiscal impacts beyond lost tax revenue: Energy companies often provide charitable contributions to schools. Three Mile Island’s owner funds a mobile library, for instance. And district leaders fear losing students, and their accompanying per-pupil aid, when well-paid and highly skilled parents employed by the plant move away.

The cautionary tales

As a new wave of superintendents contemplates a future without nuclear power plants, two towns that have already faced closures offer examples of what can happen if a worst-case scenario plays out.

When the Maine Yankee plant in Wiscasset closed in the mid-1990s, tax revenue fell by half. Expensive city assets, like vehicles, haven’t been replaced as often as they were before the closure, the police force has been cut in half and building maintenance has been delayed, longtime resident Bob Blagden, a former selectman, said.

Additionally, taxes went up. Selectman Katherine Martin-Savage, who has lived in the town for 40 years, said that before the plant closed, she paid only about $600 on an extensive property, but “You add a couple zeros to that, that’s about what I’m paying now.”

Student enrollment, declining across Maine, has fallen dramatically in Wiscasset: Graduating classes have shrunk from about 135 in the mid-1980s to about 35 last year, Martin-Savage said.

The story is similar 220 miles to the southeast, where another rural New England town, Vernon, faced the closure of the Vermont Yankee plant in 2014.

The plant brought in about a quarter of the small town’s revenue, said Josh Unruh, chairman of the Vernon select board. Owners agreed to gradually reduce tax payments rather than just abruptly end them. That helped town leaders plan, but it only dulled the impact from a 20 percent cut to the town’s budget. That meant no more town police department or full-time maintenance workers, despite a 20 percent hike in property taxes.

In Vermont, school funding is pooled at the state level and then reallocated to local districts, so schools weren’t dramatically affected, said Kerry Amidon, chair of the town’s school board.

Though there wasn’t a big financial hit to schools, passing the budget every year became more of a challenge, she said. Voters, who must approve the plan, were skeptical of higher expenditures, knowing how the drop in tax revenue from Vermont Yankee was affecting the separate town budget.

Despite the relatively small impact to the schools, “It’s been a tough couple years,” she said.

“I think the upside of everything is the community has really come together … When something like this happens, you regroup, you figure out what’s important and you figure out how to make it happen,” she said.

Ultimately, the impacts to towns and schools are more than financial, officials say. Employees at the plants, working in highly paid, specialized jobs, have to move to find comparable work, sparking an exodus of neighbors, friends and key school supporters.

“A lot of families and friends got pulled apart,” Unruh said.

At Vernon Elementary, said Amidon, Vermont Yankee engineers served as a kind of on-call tech support at the local elementary school, helping to set up computer systems and fix the gym’s wonky retractable wall.

In Ohio, the threat of closure has altered the way Parmigian, the newly inaugurated nuclear expert, sees things, too. The towers of Davis-Besse plant are no longer empty monoliths, he said. They represent the people who work inside: spouses of teachers and coaches of the high school’s volleyball and soccer teams.

“We’re closely ingrained with them. To us, it’s not a nameless, faceless entity,” he said. “It’s very personal for us.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)