In the Shadow of New Jersey’s State Capital, Trenton’s Forgotten Schools Struggle to Get Better on Their Own

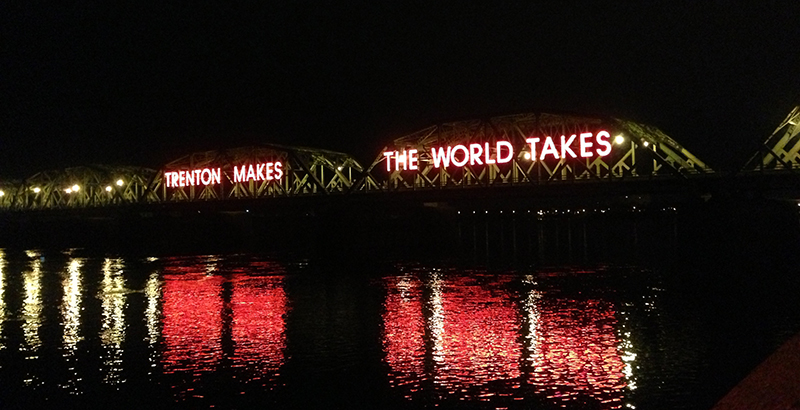

Trenton, New Jersey

Trenton rarely appears in high-flown fiction — or even in a song by its neighbor Bruce Springsteen — but it does show up in the novel Americanah, a recent favorite among the literary set.

The book opens with its Nigerian-American protagonist on her way to the train station in Princeton, unhappy to break the spell of the “tranquil greenness of the many trees, the clean streets and stately homes,” by having to travel to nearby Trenton to get her hair braided.

A taxi drops her off at a run-down salon, the air conditioner broken on a hot summer day, paint peeling, three West African women working in T-shirts and knee-length shorts — the kind of place where “often, there was a baby tied to someone’s back with a piece of cloth.”

In a moment of snobbery, she mentions her academic fellowship to Aisha, a rough and uneducated stylist from Senegal. She feels “a perverse pleasure. Yes, Princeton. Yes, the sort of place that Aisha could only imagine …”

Trenton hasn’t fared well in comparisons with most of New Jersey, let alone hallowed Princeton, for a very long time, and the squalid salon rings true as a metaphor for the city and its public schools.

New Jersey has only a handful of poorer cities, and even fewer lower-achieving school systems. But as political and education leaders touted New Jersey’s advances in education during the past decade, the poor outcomes of students in its state capital received little attention, overshadowed by Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million donation to Newark and a governor-led turnaround effort in Camden.

The issue isn’t so much intentional neglect as it is the fact that poverty-related challenges have swamped traditional solutions. Chris Cerf, the departing Newark schools superintendent who served as New Jersey’s education commissioner from 2011 to 2014, suggested the state didn’t have capacity to take over Trenton when it was already working to do that in Camden, “one of the lowest-performing districts in the country and certainly the lowest-performing district in New Jersey,” he pointed out.

“Everybody was aware that Trenton was struggling, but the opportunities for intervention were limited to the relatively conventional playbook that is available to any state,” Cerf said. “The extraordinary intervention of state takeover was simply not politically available.”

Still, it’s at least ironic that four minutes from the monumental government buildings where deals were formalized, 48 percent of students at Trenton Central High School–West were chronically absent. Several of the schools that scored among the lowest 5 percent in the state are within walking distance.

Ten Trenton schools within close proximity of the New Jersey statehouse are among the lowest ranked of the state’s 2,105 schools. (Source: New Jersey Department of Education data, 2016–17)

Trenton’s distress is unmistakable. Roughly 28 percent of the city’s 85,000 residents are poor, almost twice the state average, and 16 percent of households live on less than $10,000 annually. Nearly one-quarter of residents lack health care, and violent crime is close to the highest in the state. Math proficiency among city students, 98 percent of whom are black or Hispanic, lingers in the single digits, and six of its 20 schools scored 10 or less on the state’s new 100-point evaluation system.

“I think basically Trenton has a reputation that we’ve given up on education. Even though we know that, for one thing, it saves inner-city children, there’s no major investment in education.”

—L.A. Parker, columnist, The Trentonian

Few parents or advocates express high expectations for city or state leaders. The district has shuffled through six superintendents since 2010, some followed by scandal. Repeated attempts to convince former governor Chris Christie to visit the decaying, vermin-infested high school were unsuccessful, even though it was less than two miles from his office. School board members have moved through “like changes in the weather,” one longtime observer says. A recent mayor sits in federal prison, and his successor, the current mayor, Eric Jackson, has not made education a priority, many say.

Few will speak on the record about the Trenton Education Association, the aggressive union local, though some say it controls teaching assignments and obstructs change.

“I think basically Trenton has a reputation that we’ve given up on education,” says L.A. Parker, a local activist and columnist for The Trentonian. “Even though we know that, for one thing, it saves inner-city children, there’s no major investment in education.”

Stopping a vicious cycle

As in every system, there are sparks of hope. Superintendent Fred McDowell arrived last July after working with marquee district leaders Tom Boasberg in Denver and Bill Hite in Philadelphia and — notwithstanding de rigueur union protests — has made a mostly positive impression.

“My sole area of focus was, ‘How do we stop the bleeding?’ ” McDowell said of his first months. “The vicious cycle of the start and stop [in leadership] had been pretty pervasive for about the last 10 years.”

McDowell says he will focus on improving teaching, with principals trained to manage instruction more effectively in their schools — creating a culture of learning supported, but not dictated, by the central office.

Some Trenton principals have been able to manage the distractions, though not easily.

Dewar Wood sits casually at a meeting table in her office, amid boxes of binders and unemptied cartons of books. She looks small for the room, but her voice is principal-loud, with a warm but amazed tone, at least when talking about the status quo.

“A lot of the practices that go on here, you wouldn’t believe,” the Columbus Elementary School leader says. Teachers have the right to choose positions based on seniority in Trenton, but, she says, union officials, working out of district headquarters, direct those assignments.

Trenton, Wood says, “is a different beast. It’s so dysfunctional they think it’s functional. But I won’t accept the dysfunction. I haven’t drank the juice.”

McDowell describes Wood as a model principal, in part perhaps because of her openness, even about him. Among the staff at Trenton’s 20 schools — educating roughly 11,000 students, roughly 90 percent of whom are low-income — few will say openly, as Wood does, that “the teachers union runs the district, they will tell you what to do and when.” Or: “there’s no support from central [administrators].” Or, of some early resistance to McDowell, “I’ve seen him fizzle.”

Naomi Johnson-Lafleur, president of the teachers union, did not respond to several requests for comment.

It’s not as if Wood’s school, Columbus Elementary, is clearly a world-beater. Just 18 percent of students met expectations in math in 2017. More than 22 percent were chronically absent. Yet Columbus is a good place to learn, by most indications.

Wood has helped lift it from the bottom 5 percent in the state; it now rates higher than roughly one-quarter of New Jersey schools. Its instructional plan uses data to differentiate student needs. Classrooms are engaged, groups of classmates walk by holding glockenspiels (everyone learns to read music), and student art unfurls everywhere.

The vibe is no excuses on antidepressants: students wait in lines, but their body language is loose and warm. They step out to be hugged by Wood, and, like every good principal, she has a unique rapport with each one. The discipline problem of the day among the 95 percent–poor student population involves a boy, cowering some distance down the hallway, who “accidentally” squirted ketchup on a girl’s sweater.

Cracking the code

Trenton poses a question to philanthropists, advocates, charter operators, and elected officials who support urban reform: Is this enough to make a bet on? To build a brand on? To use as a beta test?

Columbus’s performance runs ahead of the city’s: 9 percent of its elementary school students meet expectations in math, compared with 44 percent statewide. Ten miles away, among those “adorned with certainty” in Princeton, to quote Americanah’s narrator, 64 percent meet expectations. The average SAT score in Trenton is 848; in Princeton, it’s 1302. Statewide, the average is 1075. Among the state’s 2,105 schools, three of the five worst-rated are in Trenton.

One ostensibly positive indicator — if not necessarily convincing, given poor test results and erratic attendance — is a rise in the graduation rate at Trenton Central, the main high school, from 67 percent in 2014 to 83 percent in 2016.

Teacher absenteeism is also said to be a problem, though reliable evidence is hard to find. Teacher attendance rates range between 87 and 94 percent, according to state figures, but there are anomalies and inconsistencies among that data. In the kind of anecdote one hears often from Trenton parents, Yasmeen Douglas said her daughter’s second-grade teacher at Parker Elementary went on sick leave two weeks into September and never returned. Douglas eventually pulled her child from the school.

“She didn’t have a teacher the rest of the year until she went into the charter school in November. She didn’t have homework the whole year, she didn’t even get a progress report before she left,” said Morgan, whose older son had a similar experience at Parker the year before.

Few of the big, self-styled change makers in education have a stake in Trenton, with the exception of the reform-side NewSchools Venture Fund, which has invested $215,000 in a charter school set to open next year. Smaller cities typically don’t have the cachet of big ones, although some have argued their schools are particularly worth trying to fix. Veteran schools chief Paul Vallas observed that if he could “crack the code” to the problems in Bridgeport, Connecticut, whose district he led briefly in 2013, it could be cracked in 100 other neglected mid-size cities.

He didn’t, and no one else has.

The big bets placed on Newark and Camden, by contrast, seem to be paying off. Several reports have shown the change-making power of Zuckerberg’s seemingly apocalyptic $100 million gift to Newark in 2010 was actually rather small. But it spurred a series of reforms, notably closing struggling schools, which led to gains in reading between 2011 and 2015, according to a recent Harvard University study, while math held steady.

Camden is still in the baby-steps phase. Since Christie took control of the district, installing as superintendent a talented Newark executive named Paymon Rouhanifard, who was recently floated (if fancifully) as a contender for New York City schools chancellor, graduation rates have risen to 64 percent from 49 percent. Student proficiency in ELA has gone up between 5 and 24 points in the city’s new Renaissance schools. Run in Camden by some of the country’s most successful charter groups, including KIPP and Uncommon Schools, Renaissance schools have the operating freedom of charters but draw from their local enrollment zones.

Some in Trenton point out that Harvard hasn’t conducted education research there and, while at least one local charter — Foundation Academy — is well regarded, none of the nationally successful charters operate in their city.

Not enough people who cared

Nearly every stricken city of the East was once a success story. Trenton factories built the steel rope that suspends the Brooklyn Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge. Immigrants in its iron mills produced iconic American anvils; others built tires, made cigars, produced 12,000 dolls a day, and crafted pottery — notably the lifeboat-size White House bathtub that made 350-pound President William Taft look like a jockey.

On a late December afternoon, wind off the Delaware River cut through empty streets, weedy lots and boarded-up storefronts, giving the area around downtown a Leftovers-like emptiness.

The city that invented the oyster cracker has more energy and anxiety in its neighborhoods. Kendra Knox lives in Chambersburg, once the heart of Italian Trenton, on a street of small, closely situated homes in various states of dishevelment. At 31, she’s a single mother of six and works full time as a bank teller. She dropped out of Trenton Central as a 17-year-old freshman; years later she earned a GED and credits at nearby Mercer Community College.

“It sucked,” she says of going to school in Trenton. Growing up in a North Trenton project, she attended five schools around the city. “I didn’t feel like I had enough people who cared. I’m not saying a lot of it wasn’t my own fault, but what I am saying is, even though I was the one causing my own downfall, nobody stepped in and said, ‘Hey! Why? What are you doing? Can I help you?’

“I never got that.”

On this day, she’s worried about how her 13-year-old daughter, an honor roll student who has aged out of the Boys and Girls Club, will spend her afternoons for the next five years. And she recounts with rising anger how the middle school wouldn’t let the girl into a Halloween party, apparently because she hadn’t been diligent in wearing her school uniform.

“Why would you do that to a kid?” Knox asks. She’s concerned as well that her son’s school isn’t giving him the help he needs for his learning disabilities. She believes in the importance of education but seems to take for granted that if you really need help you won’t get it — a failure she talks about as if it were an existential condition.

“I feel this city is like crabs in a bucket — everybody’s trying get to the top,” she says. “So what am I supposed to do? Yes, these are my children, and yes, I’m taking care of them. I’m not sitting home on welfare, I have a job, I have at least 30 credits of a college education. So you can see that I’m trying, but how is there no resource?”

“And this is the capital,” she adds. “You’re going to hear me say that a lot because I really don’t understand.”

‘It’s the school district’

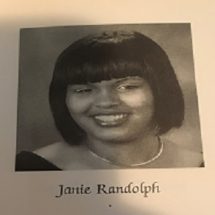

Janie Randolph, 33, attended Trenton schools but moved five years ago with her two boys to Browns Mills, about 25 miles away.

“I got them out before they were school age,” she says, as if they were hostages.

Randolph is focused and a hard worker, raised by a mother confined to a wheelchair for reasons related to heroin use. Working full time from the age of 17, she earned an associate’s degree in secretarial science at night and then later a bachelor’s degree as well.

Since high school, her career goal had been to become an executive assistant.

“Many of my peers laughed at me,” she said, but she had a plan: she could be near her mother and earn money right away as a secretary while working her way up to executive assistant. And she’d still have time to add college credentials.

Trenton Central High School, where 11th-grade social studies included learning the names of states and their capitals, had failed to prepare her for community college, however. She was assigned two remedial math classes and a remedial English class — “and mind you, I’m an A/B student all throughout Trenton High,” she said.

“Had I gone to another school district, oh my God. Like, Ph.D. … Had my schooling from K-12 had more pressure applied and been a little bit more challenging and exposed me to other things, absolutely. I made it this far just on basic math and knowing how to read.”

—Janie Randolph, Trenton graduate

Randolph ultimately parlayed a low-level gig in the mail room into a full-time position at a large company as a contract administrator. She has worked there for more than a decade.

She recalls recently watching Angela Rye, a lawyer who appears on CNN, and another black female commentator: “And I’m just like, ‘What was the difference between them [and me]’ — because it wasn’t that I didn’t apply myself. I went to school, I did the work.”

She remember being woken up one morning by a thought: “It was the school district! Had I gone to another school district, oh my God. Like, Ph.D. No doubt. No doubt,” she says with pride. “I mean, I can still do that and I probably still will do that, but had my schooling from K-12 had more pressure applied and been a little bit more challenging and exposed me to other things, absolutely. I made it this far just on basic math and knowing how to read.”

She’s withering in her own assessment of just how far that is.

“And my peers think I’m doing great things because I work from home,” she says. “They’re like, ‘Oh my God, like, you’re doing, like, great things.’ I’m really not. You know, like, in terms of where I stand in the company, I’m just a support person. But to peers, it’s like, ‘Oh, wow, you’re successful.’ And to me, I’m not successful at all.”

Christie looks for good press

Knox and Randolph came of age in Trenton while the city’s mayor was Doug Palmer, who served five terms between 1990 and 2010. Palmer’s departure would become a problem for Trenton students some years later, after his successor, Democratic Party regular Tony Mack, became embroiled in bribery and extortion charges, ending with Mack’s 2014 conviction and a five-year federal prison sentence.

Parker, the Trentonian columnist, said Mack’s legal entanglement killed local efforts to convince Christie to visit the 82-year-old Trenton Central High School building, which had become dangerously decrepit.

“When the investigation became known, Christie didn’t want to have anything to do with Tony Mack,” Parker said. “It’s understandable why he would not engage the requests at that point.”

In January 2014, a month before Mack’s conviction, NBC Nightly News broadcast a report on conditions at the high school, saying, “Right there, in the shadow of the New Jersey statehouse. A high school in such disrepair would make any parent in the country wonder about sending their child there.”

Earlier in the day, a Christie spokesman said the state would rebuild the school, according to NBC, which suggested its report was responsible for the governor’s change of course. Parker believes Christie was more concerned with generating positive press amid the accelerating Bridgegate scandal — his staff’s closure of lanes on the George Washington Bridge to create traffic jams in a city whose mayor had criticized their boss.

“With his favorable numbers tanking and subpoenas for investigations flying around like confetti, Christie needed some good press, anything to stop his slide,” Parker wrote at the time. “Remember, Christie had never set foot in the high school.”

Christie, who stepped down January 15, ended his second term as one of the state’s most unpopular governors. He did not return calls for comment. Democrat Phil Murphy, who has promised increased school funding and discontinuing the current and controversial state test, was sworn in as New Jersey’s 56th governor the next day at a ceremony in Trenton.

While Christie and Trenton’s education leaders squabbled, systemic problems in the schools evaded remedy. In the 1980s, Trenton was designated one of 28 poor cities (including Camden and Newark) the state was required to provide with increased funding to ensure equity. In Trenton, as elsewhere, much of the money was spent on salaries and benefits for a veteran teacher workforce or squandered through poor fiscal management, and triaged on an aging physical plant. A disputed 2012 state study found that score gains in these districts were no higher than in high-poverty districts that hadn’t received the extra funding.

Recent budget shortfalls forced hundreds of layoffs in Trenton schools and kept the cost of funding charters an open wound. (Several charters have been closed by the state; last week, the state’s education commissioner announced she would close low-performing International Academy, which had just completed a $17 million renovation.)

Authorization of the NewSchools Venture Fund–backed Achievers Early College Prep charter, which will open in the fall with 90 sixth-grade seats, reflected the angry politics of school choice. Efe Odeneye and Osen Osagie, sisters who grew up a few miles downriver in Willingboro, say their desire to open a school in Trenton was partly inspired by teaching in other hard-hit cities and most recently working in Newark and Camden.

“You see all of these great things happen and two cities are rewriting their stories,” said Odeneye. “Here in Trenton, our capital, which is much closer to home for Osen and I, you had a couple of shining lights like Foundation Academies [charter school], but there was just no attention to Trenton.”

Because of the financial hardship imposed by funding charters, Trenton asked the state a few years ago to freeze new applications; Achievers was approved anyway. The teachers union was livid, but McDowell, the superintendent, not yet on the scene when Achievers applied, took a more pragmatic position.

“We continue to believe this isn’t the time for charter expansion,” said Alexandrea Robinson-Rodgers, his chief of staff. “But until we improve the level of learning in the district, we’re not going to criticize other people who are trying do that.”

A fascinating place

Trenton’s school leaders have repeatedly been tied to improper or unlawful schemes. A 2007 state investigation found that the former superintendent, who left the previous year, had been aware that Trenton Central administrators falsified students records. His successor was criticized for fiscal mismanagement before leaving for hernia surgery and never returning.

Last September, McDowell’s interim predecessor was fired for selling knockoff T-shirts for personal gain before a football game.

The mayor-appointed school board has been even more of a carousel. In 2014, four of the nine members resigned, and the board was unable to have a quorum until Mayor Eric Jackson appointed member Jason Redd to an additional term. Three years later, Redd resigned from the board a month after being named chair. Both he and his predecessor, who said he left because of union “bullying,” were opposed by union leaders.

The bullying complaint may be less effete than it appears. A senior official who asked not to be named in order not to damage city-labor relations said the lack of decorum by union leaders at private meetings — including screaming and insults —“has blown my mind.”

The union’s website suggests it may face more serious issues with some frequency. It includes pages dedicated to “what to do if arrested” and instructions “if you are accused of child abuse.”

Parker doesn’t believe Mayor Jackson will deliver on education and sees little interest coming out of the legislature. But he believes city residents can begin making improvements that will pull the government with them.

“We’re a fascinating place, man. If we could ever get this education piece down pat, you’d see Trenton take off.”

Jackson, who announced Friday he would not seek a second term, did not respond to requests for comment.

Much of the enthusiasm in Trenton originates outside of government. Palmer, the long-serving former mayor, runs an ambitious effort to teach early reading called Trenton Literacy Movement. He is working to enlist the entire city in the cause.

“I’ve very hopeful about Trenton,” he says. “I actually look at it through the eyes, not of a politician, who may have been characterized as looking at things through rose-colored glasses, which I didn’t, but I’m looking through the eyes of a citizen, a volunteer, someone who’s working in the community and is seeing firsthand the real work of people that you don’t ever hear about.”

George Sowa, the optimistic CEO of Greater Trenton, a nonprofit launched in 2016 to attract industry and economic development to the city, has also become one of the capital city’s most effective cheerleaders.

“Twenty thousand state workers come into the city every day,” said Sowa, a Trenton native who led a similar, successful effort in Camden. “There are so many opportunities, but we haven’t done a good job in talking about them.”

Most Trentonians will need convincing. The prevailing strategy for success in this troubled city seems to be Principal Dewar Wood’s. She spent years in hearings and mediations fending off union attacks, sometimes originated by her own staff.

To continue building on success, “you almost have to be on a little island blocking everyone out,” she says. “And that’s sad.”

Cerf, the former education commissioner, has seen similar challenges in several big districts seriously in need of turnaround.

“Here’s the dirty truth about this business,” he begins. “We’ve got this playbook, right? It’s like, data-driven decision-making, and personalized learning, and empowering parental choice, and high standards and high expectations and Common Core this and educator efficacy that. But the truth is that most incredibly poor urban districts don’t have the ability to implement the playbook, and even those who do, only put a dent in the problem.”

After a pause, he adds: “If you don’t have political will and leadership to at least implement the playbook, then you’re basically investing in a broken system and saying, ‘Well, we’re going to keep doing what we’re doing and we’re hoping it’s going to get better.’ And it doesn’t work.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)