In Pandemic’s Isolation, an Alarming Number of Teenage Girls Are Attempting Suicide

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

For 24/7 mental health support in English or Spanish, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s free help line at 800-662-4357. You can also reach a trained crisis counselor through the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by calling 800-273-8255 or texting 741741.

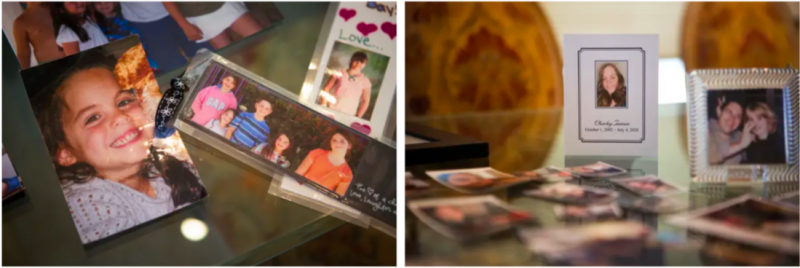

Growing up, Charley Tennen was rarely alone. The youngest of seven kids in a loud, busy house in El Paso, she was always out at a party, shopping with friends or organizing a road trip.

Even after she was diagnosed with a chronic illness and had a feeding tube inserted, she kept her bubbly personality, her mother, Michelle, said.

But when COVID-19 hit Texas in March 2020, all of that suddenly went away. Charley went from attending school with a few thousand students to sitting alone in her bedroom, doing virtual classes. She and other family members were immunocompromised, so they fully isolated themselves, terrified of getting sick.

Then, in April 2020, Charley’s beloved father died unexpectedly from complications of a chronic illness.

“She was so isolated, she had nowhere to turn,” said Michelle. “She told me every single day, ‘I want to die. I want to be with daddy. I don’t know what’s on the other side, but at least I won’t be in pain.’”

Michelle leapt into action. She got Charley a psychologist. They created a safety plan. She found an inpatient treatment facility with open beds. She kept Charley in her sights constantly, even sleeping with her at night. She asked teachers, doctors, family, friends and — after Charley attempted suicide the first time — even the police for help.

“I could barely get through each minute. I was petrified,” said Michelle. “You can’t pin yourself to somebody 24 hours a day, but I really tried.”

Despite her mother’s tireless efforts, on the night of July 4, 2020, Charley Tennen died by suicide. She was 17 years old. Michelle held her second virtual funeral in three months.

“Losing [my husband], I thought would be the hardest thing I’d ever go through,” she said. “But burying my baby girl — there are no words for burying a child. And a child that should still be here. This never should have happened.”

The riptide of despair that caught Charley Tennen and carried her away from her family is only strengthening as the pandemic enters its third year.

Across the country, teenage girls are attempting to end their own lives at staggering rates, driving a 50% increase in girls being admitted to the hospital for suspected suicide attempts between early 2019 and 2021.

Although teenage boys remain more likely to die by suicide, teenage girls are more likely to attempt it.

The surge in extreme mental distress has left parents, schools and health care providers scrambling to get urgently needed help from a broken mental health care system.

And it’s an indicator that there’s a much bigger crisis looming as the pandemic drags on.

“For most kids, you’re not going to see suicidal ideation or suicide attempts,” said Kim Roaten, a psychiatry professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. “Instead, you’re going to see withdrawing from friends or dropping grades or more argumentative at home, things like that. What we want, ideally, is to prevent the escalation.”

Pandemic increased isolation, grief

Michelle Tennen had raised six other children. She knew how to navigate the minefield of adolescence. But nothing prepared her for helping a grieving teen through a pandemic.

“It’s just so hard to be a teen girl at any time,” said Michelle. “But to then be isolated and going through a pandemic, too. It’s the isolation, in my daughter’s case, that was the big problem.”

Charley would sit in her room, looking at the same four walls or mindlessly scrolling through her phone. Michelle would encourage her to call friends.

“She’d say, ‘No, I don’t want to talk to them,’ or ‘They don’t want to talk to me,’” she said. “As the months went on with the pandemic, you could see the change in her and how much more isolated she got.”

Even before the pandemic, researchers were documenting alarming increases in anxiety, depression and other mental health concerns among teenagers. There are some positive trends — young people appear more open to discussing their mental health than previous generations.

But it’s also just hard to be a teenager today, with increased internet access, academic pressure, limited access to mental health services and economic and social stressors.

During the pandemic, teens had to navigate those challenges amid increases in isolation, screen time, grief, caregiving responsibilities, economic insecurity and school interruptions.

Molly Lopez, the director of the Texas Institute for Excellence in Mental Health at the University of Texas at Austin, recently convened a focus group of teenagers to talk about mental health concerns. She said they all shared the difficulty of focusing on school work and normal milestones when they, their families and their communities were experiencing so much stress.

“They were really struggling with feeling like their teachers didn’t understand what they were going through,” she said. “We’re using the same playbook as before the pandemic, with the same expectations.”

Schools are also having to help students navigate grief, as many have lost loved ones to COVID. One in 450 children in the United States had lost a parent or caregiver to COVID, as of November 2021, according to researchers at the University of Pennsylvania.

All of these factors have created a “stressor storm” for teenagers, especially as schools return to in-person learning, Lopez said.

“Some kids may act on those challenges in ways that are hurtful, so you may see more violence or interpersonal problems,” Lopez said. “Then, some students who are at risk for suicidal thoughts, that increases their risk.”

Lopez said, ideally, schools would have a three-tier system for helping students with mental health issues. They’d have resources to help all students talk about and improve their mental health; they’d have systems in place to identify and intervene early if students start showing signs of mental distress; and they’d be prepared to handle students who are actively in crisis.

While school districts have been investing more in building these systems in recent years, the pandemic made all of that much more difficult at a time when the need has only escalated.

Challenges to getting help

Michelle Tennen knew that Charley was struggling with isolation and grief. But it wasn’t until she saw, through a shared iCloud account, that her daughter was looking at photos of coffins online that she realized how serious things had become.

Charley began speaking very openly about her desire to kill herself, shocking her mother. But Michelle was just as shocked by how difficult it was to find help for her daughter.

“I did not stop trying to get help from her until the day she died, and I could not get help,” said Michelle. “It’s unbelievable that in a country like this … the mental health system is in the shape that it is.”

Michelle said she heard time and again from doctors, treatment facilities and even the police that Charley didn’t “seem suicidal.” When she met with doctors, therapists or treatment facilities, Charley would deny being suicidal to avoid being admitted. One psychiatric hospital where Michelle tried to get Charley admitted said they could only keep her for 72 hours without her consent.

“I was very worried that I would take Charley to the psychiatric hospital, they’d release her after 72 hours, and then I’d be in a worse position because she’d want to die and be mad at me,” Michelle said. “I didn’t want to give her any ammunition.”

Michelle thinks a lot about how difficult it was seeking treatment for a teenager actively expressing suicidal ideation — and what that means for teenagers who need help before they even get to that stage.

In Texas, nearly three-quarters of teens experiencing serious depression do not receive any mental health treatment, according to a report from Mental Health America. Texas ranks last among the states in access to mental health services.

Statewide, there is a significant shortage of mental health resources — inpatient beds, outpatient treatment spots and mental health providers. Every county is served by a local behavioral health authority that can help people in immediate crisis, but ideally, teenagers would get help well before that point.

“In a crisis situation, help is available, no matter where you are in the state,” said Greg Hansch, the executive director of the Texas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Health, in a December interview. “But the ongoing, robust services that so many people need and will need in the days to come are spotty across the state. We need ongoing efforts to address that shortfall in capacity.”

Unless the mental health system scales up significantly, teenagers are going to fall through the cracks with tragic consequences. A 2021 advisory from the U.S. Surgeon General warned that it would be “a tragedy if we beat back one public health crisis only to allow another to grow in its place.”

There are some bright spots: The pandemic has helped usher in a new era of telehealth, increasing mental health resources in many underserved communities, and some researchers hope that the increase in emergency room visits for suicide attempts may be driven, in part, by greater awareness among parents.

“Kids are constantly with their parents right now, particularly when we were in the virtual period,” said Roaten. “It may be that there have been more conversations between adolescents and their parents about distress and mental health.”

Having the tough conversations

Experts agree that the best thing parents can do if they are worried about their teen is to have the conversation, early and often.

“I think for parents, it’s really frightening sometimes to wonder if your child might be having thoughts of hurting themselves,” said Lopez. “Parents need to normalize having a discussion with a young person about how they’re feeling, and being able to help them put words to the emotions that they may be feeling, and the stressors that they may be feeling.”

Michelle Tennen is glad she was able to have those conversations with Charley before she died. She feels she did everything she could to try to help her daughter, but, she said, “parents can’t do it alone.”

After attempting suicide just a month earlier, Charley ended her life in July 2020 by crushing up medication and putting it in her feeding tube.

After Charley died, Michelle Tennen remembers seeing that a family friend had posted on social media, saying that it had been a suicide. She asked them to take it down.

“Then an hour later, after I’d had time to digest it, I realized my mistake,” she said. “I tried to squash something that we needed to bring attention to. That was a big lesson I learned from the teenagers.

“We don’t squash it. We talk about it.”

Since then, she’s been sharing Charley’s story in hopes it will help people realize they’re not alone with these struggles. At least once a week, she hears from other parents who are watching their children go down a similar road — anxiety, depression, isolation, suicidal ideation.

They couch it in nicer terms, but Michelle knows what they’re really asking: How can they avoid the nightmare she experienced?

“I tell them … just keep knocking on doors, yell as loud as you can until you get somebody to listen to you,” she said. “But I replay what happened with Charley over in my head every single day, some days more than others. And I don’t know what I could have done differently to change this outcome.”

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Eleanor Klibanoff is the women’s health reporter at The Texas Tribune, the only member-supported, digital-first, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues. This article originally appeared on Feb. 1 at TexasTribune.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)