How Norway Cut Student Absences By 25% — And Why The Policy Is No Silver Bullet

In 2016, students who missed more than 10% of hours in a course automatically flunked it. But experts say U.S. students need supports, not punishments

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

In 2016, Norway instituted a policy meant to curb student absences in high school. Students who missed more than 10% of instructional hours in any given subject would not receive a final grade in the course, effectively flunking it.

Despite heavy pushback from students, the change had its intended effect. The new rule reduced overall absences by 20-28%, according to a working paper published in July by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“There is a quite substantial impact on absenteeism,” explained co-author Nina Drange, an economist at the Frisch Centre and Statistics Norway. “These students do indeed reduce their absences.”

What’s more, it became much rarer for students to miss school days en masse. Some 29-39% fewer Norway high schoolers were what researchers call “chronically absent,” missing more than 10% of all school days. Chronic absenteeism remains one of the pandemic’s most serious consequences for U.S. schools.

In Norway, the policy change produced a “sharp” drop, Drange observed.

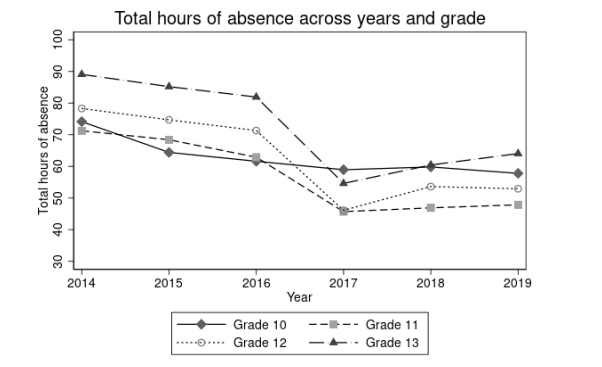

Drange and her colleagues were able to document the policy’s impact by comparing Norway high schools students in 11th-13th grade, who faced the strict consequence of missing multiple classes, with 10th graders who did not. That ruled out the possibility that observed changes between the two groups were caused by other factors. Absences among the older students saw a steep decline while the 10th graders’ rate held mostly steady.

Experts highlight the risk of chronic absenteeism and the 10% absence threshold because it can predict reading difficulties by third grade, failure to earn a diploma in high school and higher risk of juvenile delinquency later in life.

Now, with the American education system still reeling from the pandemic, many school leaders are concerned with the amount of instructional days their students are missing. Rates of chronic absenteeism have skyrocketed nationwide, hitting 40% in the nation’s two largest school systems, New York City and Los Angeles.

“We believe that chronic absences doubled across the country, maybe more” since COVID struck, said Hedy Chang, who closely follows the issue as executive director of Attendance Works.

She estimates the issue affected 16% of students nationwide before the pandemic and now affects over 30%. Missing school has escalated into a “full-scale crisis,” a June report from her organization said.

Those increases came partly because students were forced to miss class for quarantine. But also because of social factors, such as youth needing to pick up jobs to support their families, having spotty internet connections during remote learning or being fearful of catching the virus at school.

Those are underlying conditions the Norway rule can’t solve, Chang points out.

“The policy itself doesn’t address root causes,” she told The 74.

The Norwegian government supports unemployed families to a greater degree than the U.S., added Drange. If students were missing class because they had to pick up jobs to financially support loved ones, “I guess we wouldn’t see these huge effects” from the no-grade policy, she said.

Further, Chang worries that penalizing students who miss a higher share of school would disproportionately affect youth who already face severe disadvantages, putting them even further behind.

“I’m concerned that … the grading approach will exacerbate existing inequalities,” she said.

The Gini index, which measures inequality on a scale of zero to 100, with 100 being most unequal, rates the United States a 41.5 and Norway a 27.7, indicating that students in the Scandinavian state may begin from a more level playing field than American youth. Furthermore, obtaining a doctor’s note to explain an absence due to illness, an exception to the no-grade rule in Norway, could pose a greater challenge in the U.S., where universal health insurance does not exist, the Attendance Works executive director pointed out.

Through much of COVID, Norway suspended its no-grade policy, said Drange. Though the very youngest students in the country went back to in-person learning after less than a two-month shutdown, localities took varying approaches for older students.

Even when the no-grade policy was in effect, Drange’s research indicates that the rule had a modest positive effect on teacher-awarded grades, but little impact on externally graded end-of-year assessments — a disappointment for those who hoped stronger attendance would automatically spell increases in achievement.

In the U.S., with poverty-related issues and mental health posing a key barrier to school attendance, Chang says education leaders should use the 10% absence threshold to identify which students might need extra support — not to punish them as truant.

“If you’re experiencing bullying, if you’re experiencing lack of access to health care, if you’re experiencing unreliable housing situations, those conditions are … affecting your learning, in addition to causing you to not show up to school,” she said.

“Could [schools] create options so kids have another way of making up the time?”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)