How New Orleans Schools Are Making Up Special Education Losses From the Spring Pandemic Shutdown — and Why the Process Could Improve Distance Learning This Fall

By law, U.S. students who are wrongly denied special education are entitled to something called compensatory services. Typically, getting them follows a long and bitterly contentious process that starts when a parent or advocate complains that a needed service was withheld. If a student’s rights are found to have been violated, a plan is drawn up to make up for what was lost.

Even under normal circumstances, getting special education services can be a challenge. But as schools struggled to shift to distance learning in March, very few students with disabilities received much, if any, of the special education they were supposed to be getting. And now, weeks into the new school year, special education students throughout the country still aren’t receiving the most basic services — let alone extra help making up for last spring’s lost learning.

But in New Orleans, even as classes remained remote, a number of schools started catching their special education students up over the summer, evaluating whether they have regressed and strategizing about the best ways to help them bounce back. Now, as students are starting to come back to schools in person, educators are refining those plans and assessing whether their special-needs students need more individual support.

Schools credit a push from the state, which prioritized providing assistance aimed at boosting the quality of distance learning, for their swift move to address special education losses. Over the summer, state officials urged schools not to wait for complaints to roll in to begin providing compensatory education.

Under the Louisiana Department of Education’s Strong Start Compensatory Service plan, school reopening blueprints for the fall had to include plans for addressing services special education students missed. Once schools reopened, they had a month to assess individual students and decide how to start helping them catch up.

Staff at Crescent City Schools in New Orleans jumped right in. In July, they gathered data on students with disabilities in the three schools in their network. Because of COVID-19, there were no end-of-year exams, but staff compiled records outlining special education services delivered or postponed in the 2019-20 school year, reports of progress on students’ Individualized Education Programs — the documents that spell out their goals and the services necessary to meet them — and academic assessments delivered periodically throughout the past school year.

The data was imperfect, but it was enough to get started, says Kevin Lapinski, the charter school network’s director of special education. “We waited long enough,” he says. “Kids need to be getting the services they deserve.”

Almost immediately after the state issued its instructions, Crescent City Schools started bringing back, in very small numbers, students needing in-person services such as physical, occupational or mental health therapy, or physical education adapted for children with gross motor challenges. Almost all families with children who needed the assistance chose to participate.

Meanwhile, special education case managers gathered information from the last school year, as well as whatever fresh data was practical. “We looked for places where a student was progressing last year and then that stopped,” says Lapinski. “We administered diagnostic [assessments] in person when possible, and when not, over Zoom.”

Using students’ existing IEPs, teachers drew up contingency plans. Since school resumed online in August, every class has had at least two teachers. One delivers instruction while the other tends to students who need individual support.

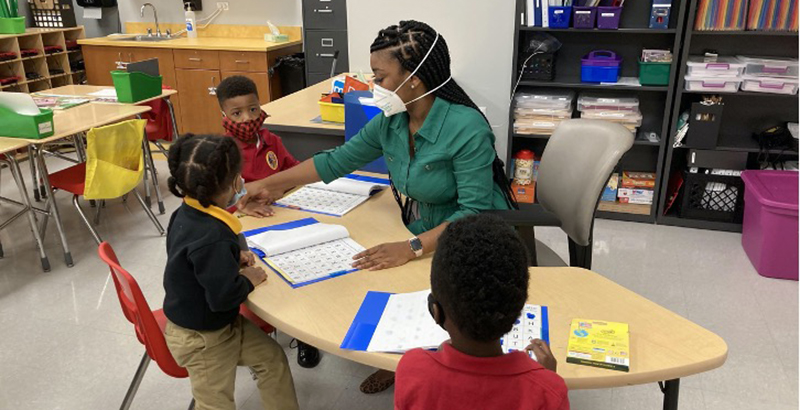

In mid-September, students in fourth grade and younger were allowed to return to class. This has enabled Crescent City Schools to complete in-person assessments that will provide more current and precise data.

‘There are still a lot of unhappy families out there’

In terms of special education, New Orleans is an improbable place to call a bright spot. Ten years ago, a group of students sued the district, then known as the Orleans Parish School Board, and the state, demanding dramatic improvements in special education in the city’s schools. The 2014 landmark settlement of that class-action lawsuit focused attention on longstanding deficits.

As the 2020-21 academic year opened, some individual schools in the nearly all-charter district were making headlines or facing official scrutiny for ongoing failures to serve students with disabilities. But many others put together strong plans to provide compensatory education, advocates say.

The existence of those plans puts New Orleans at the forefront nationally, researchers say. Analysts at the Center on Reinventing Public Education recently reviewed school reopening plans for 106 districts and found that just two, California’s Fresno Unified School District and Boulder Valley School District in Colorado, mention compensatory services. More than 10 percent don’t include special education at all.

While hard data is elusive, it’s clear the need is great. Recent research from Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes suggests students may have lost the equivalent of up to a year’s growth in reading and up to 232 days in math, with the most vulnerable students likely to have experienced the sharpest losses.

Adding to this is the likelihood that special education students got even less meaningful instruction than usual in the spring. Results of a survey released in May by the advocacy group Parents Together showed four in 10 parents of children with disabilities said they were not receiving any services and only one in five was getting everything the IEP called for. More than a third were receiving little or no remote learning.

As schools reopened in August and September, parents in many places complained they still had no idea what special education would look like in the new academic year. Some, who in the spring had struggled to replace the battery of specialists who supported their kids in school, were dismayed to learn the fall would be no different.

“There are still a lot of unhappy families out there,” says Lanya McKittrick, a research analyst at CRPE. “I was really hoping districts would learn from the spring.”

Lauren Morando Rhim, executive director and co-founder of the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools, notes that when schools first shut down in March, the U.S. Education Department warned that the pandemic did not change their obligation to provide special education.

“They said do what you can do and defer what you can’t,” she says. “In the short term, this is a workable strategy — if, say, this had been over in July.”

The department was clear at the start of the pandemic that however long schools are disrupted, compensatory services will be required if students with disabilities lose ground or can’t get some services at a distance. But it’s not clear most schools know whether or how much their special education students have regressed.

“One of the things I’ve observed is they’re not doing assessments,” Morando Rhim says. “Then how do you know where kids are?”

Aqua Stovall is executive director of the Special Education Leader Fellowship, a New Orleans nonprofit that trains teachers and principals to provide high-quality services for students with disabilities. Since March, the organization has used funding from New Schools for New Orleans, an organization working to increase the quality of the city’s public charter schools, to consult with schools on providing effective special education during the pandemic.

The state’s mandate that schools plan for compensatory services in addition to the interventions spelled out in students’ IEPs pushed educators, says Stovall. “It made schools really think through their re-entry,” she says. “The thing we as a community are trying to do is say, ‘What does this mean and how do we use this to drive students’ results?’”

In addition to providing training and coaching, Stovall’s program has offered virtual school walk-throughs to review how special education services are being provided and reviewed individual school reopening plans. The nonprofit also assembled a reopening toolkit for principals and teachers featuring resources on staffing, planning, monitoring progress and ensuring academic materials and settings are accessible to all students.

Crescent City’s approach — to gather baseline data on students — shows up in lots of New Orleans school reopening plans, Stovall says. Systems needed to measure learning losses among students with IEPs also reveal whether services, compensatory or not, are leading to progress.

As schools redesign what classes will look like for an indeterminate period of time, this focus on student outcomes is especially important, she says. “I’m telling you, it’s not what we can’t do, it’s what we can do,” says Stovall. “We have to reimagine instruction, because when we didn’t do it before, we saw what happened.”

Advocates say that besides making services available as quickly as possible, the process of assessing where each child is now and brainstorming new ways to help them meet their goals could make special education — pandemic or not — stronger.

“We have taught the same way for 1,000 years,” says Cade Brumley, who took over as state superintendent in June. “And now in a few months we’ve flipped the switch.

“It’s really a time for partnership between the educational institutions and their teachers and leaders and advocates.”

Meeting the moment with creativity

On the first weekend of October, New Orleans schools got permission to begin bringing back fifth- through eighth-graders in person, either full time or on a hybrid schedule. Crescent City’s older students will resume classes in person two days per week, starting the week of Oct. 26.

With students with disabilities back in their classrooms, it will be easier to monitor whether compensatory services are in fact working, or whether more or different services are needed, says Lapinski.

The Louisiana Department of Education in September surveyed schools to find out how many had completed compensatory services reviews, says Brumley. Some 90 percent of districts reported having assessed students and created plans. The department is following up with the remainder to learn what hurdles might exist.

Once his department has an idea what barriers schools are facing and what’s going well, Brumley says, Louisiana expects to direct some of its federal CARES Act stimulus dollars to help schools pay for compensatory services. In the meantime, he has urged schools to involve families and special education advocates when it comes to these and similar issues.

“We have to have our ears open, our minds open to hearing what people have to say about delivering education to the kids they care about,” he says. “How do we meet the moment with creativity and flexibility to get each child the services they need?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)