How Catholic Nuns Brought Education & Female Empowerment to Millions of Children, Women & Immigrants by Teaching Students on the Fringes

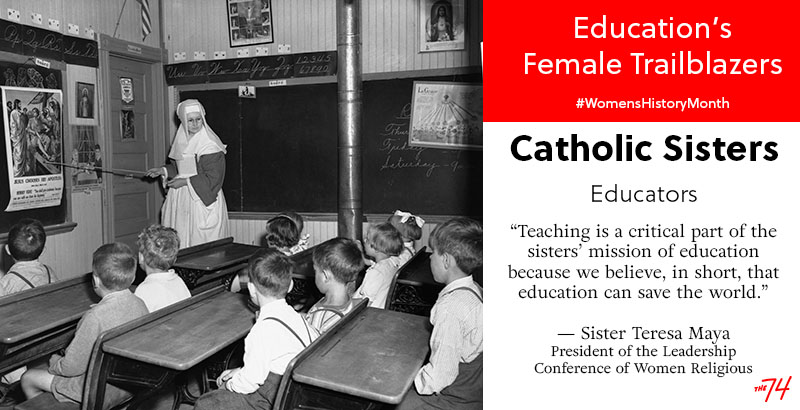

March is National Women’s History Month. In recognition, The 74 is sharing stories of remarkable women who transformed U.S. education.

A self-described young, stuttering child, Joe Biden credits a group of women for building his confidence and giving him 12 years of education that would lead him to become vice president of the United States. “You have no idea of the impact that you have on others,” Biden told a group of Catholic nuns on a social justice tour of the United States in 2014.

Biden is just one of millions of Americans, many of them underprivileged, educated in Catholic schools, a system that would have been impossible if not for the generations of dedicated religious female educators. Working for very low wages, these women changed lives, moving large immigrant communities into the middle class and — though too often given short shrift by the male-dominated Catholic Church — opened doors to higher education for women.

“Teaching is a critical part of the sisters’ mission of education because we believe, in short, that education can save the world,” said Sister Teresa Maya, president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. “It empowers people, it broadens horizons, it deepens values, it engages conversation between faith and culture.”

Catholic schooling in the U.S. dates back as far as the early 1600s, as priests and nuns arrived in the colonies and established schools, orphanages, and hospitals. John Carroll — elected the first U.S. bishop in 1789 — pushed for religious schools to educate American Catholic children living in a predominantly Protestant country. As priests and brothers began creating schools for boys, it was left to the nuns to teach girls.

Elizabeth Ann Seton, recognized in the Catholic Church as the first native-born U.S. saint, started the Sisters of Charity, an order that opened separate parochial schools for families of poor and wealthy girls, in the early 1800s. Some consider these the first Catholic parochial schools in the U.S.

By the middle of the century, Catholics from Ireland, Italy, and Poland began immigrating to the United States and swelling the ranks of local churches, and in the early 1900s, bishops called for every parish to educate its children — a response to widespread anti-Catholic sentiment, a need to help Americanize the new arrivals, and a desire for an alternative to public schools where children prayed the Protestant version of the Lord’s Prayer and read the King James version of the Bible.

Most of this work was carried out by the nuns, who took vows of poverty and could teach children for very low wages.

“Without the nuns, you could not have had the parochial school system that this country has had,” said Maggie McGuinness, professor of religion at La Salle University.

Catholic schools were also invaluable in alleviating overcrowded public schools as populations surged in major cities, and giving immigrants a boost up the economic ladder, said Ann Marie Ryan, associate professor of education at Loyola University Chicago.

“(The nuns) moved entire groups of people into the middle class, which is a substantial feat in and of itself,” she said.

Still, anti-Catholic sentiment proved pervasive. As Catholic groups tried to obtain public funding for their schools in the late 1800s, states began passing Blaine amendments, which restricted state legislatures from using funds for religious schools. Today, 37 states have these laws.

Oregon even instituted a law, backed by the Ku Klux Klan, that prohibited students from attending Catholic school. The U.S. Supreme Court struck this down in Pierce vs. The Society of Sisters in 1925.

As the sisters fought for their students’ rights to be educated in Catholic schools, they also found themselves fighting against the church patriarchy for their own pursuit of higher education. As Ryan wrote, “The Catholic Church’s hierarchy in the USA was worried about the movement toward increased independence for women in this era.” To fill a need for higher education among Catholic-educated girls, more nuns began seeking Ph.D.s so they could lead Catholic colleges for women. But this pursuit of independence didn’t sit well with their governing bishops, and they pushed back.

For example, in the 1930s and ’40s, the archdiocesan board of Chicago mandated that nuns could not travel outside a convent or school without being accompanied by another woman, and even went so far as to tell the president of a neighboring college that nuns should not show up to their classes without a female companion. They were also not to go outside after sunset.

Mission statements of all-girls Catholic schools reflected the sisters’ challenge of balancing what the church considered the natural role of women with many young women’s desires for independence, Ryan wrote. When the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary established Mundelein College in 1930 in Chicago, they crafted goals that showed these dual perspectives: “(Mundelein education is) practical, preparing the student for successful achievement in the economic world,” but also “conservative, holding fast to the time-honored traditions that go to the fashioning of charming and gracious womanhood.”

“(The nuns) highlighted and equally lauded their graduates’ choices to marry, seek employment, enter a religious community, or attend college,” Ryan wrote.

In her research, Ryan found Catholic high school yearbooks that revealed what this opportunity meant to young women. At Chicago’s Catholic Mercy High School in 1927, the students published quotes from Tennyson’s poem The Princess: “Here might we learn whatever men are taught…knowledge is now no more a fountain sealed.” Sixty percent of Mercy’s graduates around this time attended college (nationally, female enrollment in higher education was 44 percent).

At a time when women were barred from many universities, nuns became their advocates. Catholic sisters established 150 religious colleges for women in the United States, starting in the late 1800s. Before coeducation of men and women became the norm, more women were earning degrees from Catholic colleges than those run by other religious groups, according to The Boston Globe. And the nuns’ own pursuit of higher education broke glass ceilings: The first woman to obtain a Ph.D. in computer science was a nun: Sister Mary Kenneth Keller, in 1965.

“They were role models,” McGuinness said. “If you went to Trinity University in D.C. in 1897 and had teachers who had doctorates, maybe you think, ‘I could do that, too.’”

Maya certainly experienced that when an older nun, Sister Rosa Maria Icaza, told her what she had to go through to earn her doctorate from Catholic University. Because enrollment was limited to men, the nun had to sit outside the classroom, near the door, rather than inside with her male classmates. “I thought, ‘Thanks to a woman like this, I could get a Ph.D.,’” Maya said.

Today, however, the number of religious leaders in the Catholic Church is declining, including nuns. From 1965 to 2017, the number of sisters decreased from 179,000 to 45,000, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate. And even in the face of this decline, the women who join the religious life are still finding themselves under fire from within their own church. As recently as 2012, American nuns were accused by the Vatican for being radical feminists.

The loss of nuns as a teaching force is one reason running Catholic schools is more financially challenging than ever before, Maya said. Catholic school enrollment peaked in the 1960s and has dropped significantly since then. In 1965, about 5 million children attended Catholic elementary and secondary schools. In 2017, enrollment was just under 2 million. The number of Catholic schools was cut in half, from 11,000 to 6,000, during that same time period.

Catholic schools today have been experimenting with different business models to survive, from the Cristo Rey schools that utilize student work study to help pay for tuition to Philadelphia Catholic schools that have been using tax-credit scholarships and voucher programs to pay tuition for poor families.

And their students no longer come primarily from their local church — many see Catholic schools as a better alternative to poor-performing urban schools. “In many major cities, Catholic schools are a parent’s best hope for both Catholic and non-Catholic kids,” McGuinness said.

Maya said she is proud of the work Catholic schools are continuing to do to reach the children who need it most.

“The sisters were always teaching the populations in the margins,” Maya said. Without these women, “I don’t think the U.S. Catholic education system would exist the way we know it.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)