Greene: For Students to Get Back to Normal, They Need Support, Not Punishment

Concerning behaviors are caused by academic and social demands students are having trouble meeting, especially when schools double down on discipline

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As a clinical psychologist who has consulted for districts across the country for the past 30 years, I’ve seen a lot. What I was seeing during the last three months of school, as America’s students and educators wrapped up their first sustained stretch of in-person instruction in years, were more kids than ever whose behavior was out of control — and school staff who were running on fumes.

In many states and districts, the approach to school discipline is archaic: punitive, exclusionary strategies such as detention, suspension, expulsion, restraint, seclusion and corporal punishment. These interventions never helped students, but they are especially damaging now. Not only are they ineffective tools for improving behavior, they push students away from the people who should be helping them.

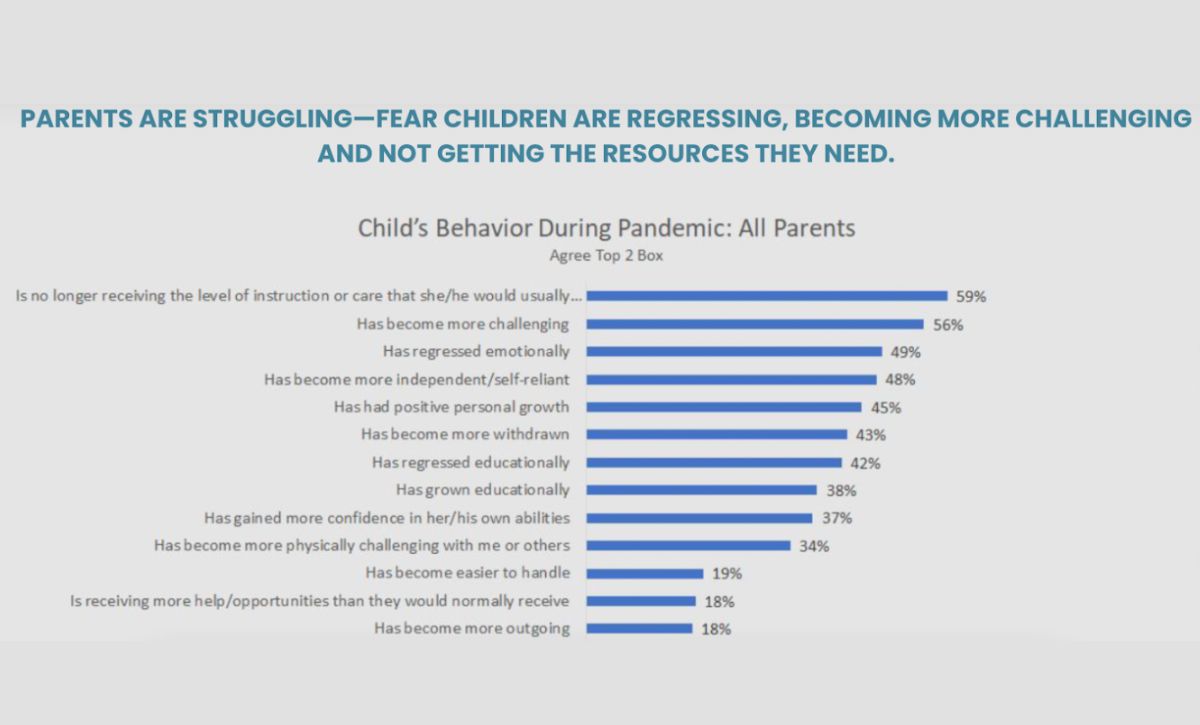

According to research by the nonprofit I lead, Lives in the Balance, 56% of parents say their child’s behavior became more challenging during the pandemic, and 49% say their child has regressed emotionally. That’s what educators are dealing with as the pandemic recedes.

Many of these students are not able to get back to normal just yet. During the spring, they communicated this by screaming and destroying property or being physically aggressive and running out of class. In Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin, Rachel Polacek, a school psychologist and colleague, told me that nothing compared to the sheer volume of students filling her office. “They come to school anxious,” she says, “and it’s increasingly hard for them to regulate their behavior.”

These concerning behaviors are precipitated by academic and social expectations students are having difficulty meeting, especially in schools that are doubling down on business-as-usual discipline.

In Collierville, Tennessee, for example, a teacher taped a student’s mouth shut to curb “excessive talking.” In Lawrence County, Alabama, a school principal was placed on leave after repeatedly paddling a third grader.

These obsolete, counterproductive tactics remain surprisingly common, even when they don’t make headlines. Corporal punishment is still legal is 19 states, where it is used on students over 90,000 times every year even though it is conclusively linked to negative outcomes for children across countries and cultures. These include worse physical and mental health, impaired cognitive and socio-emotional development, poor educational outcomes, increased aggression and perpetration of violence.

Other punitive and exclusionary discipline practices can have equally harmful effects. Nationwide, 98,000 students are physically restrained or placed in seclusion at school annually. U.S. schools expel more than 100,000 students each year, adversely affecting outcomes such as graduation, earnings and mental health as adults. Over 500,000 kids are suspended in or out of school every year, and another 230,000 are referred to law enforcement, fueling the school-to-prison pipeline. And these are probably underestimates.

Study after study has confirmed these practices do nothing to improve student behavior; to the contrary, they push out the most vulnerable kids. But many educators already know the right place to start.

In August 2021, I asked 200 special education administrators at a conference in Albany, New York, about their worst fear as the pandemic receded. It was that there would be pressure to get back to normal too quickly. I also asked about the best thing about education during the pandemic, and they said it was being given permission to meet every kid where they were at, no matter what it took. As we navigate these uncharted waters, that commitment — not a rush to return to normalcy — should be our lodestar.

For the past 30 years, I’ve helped schools implement Collaborative and Proactive Solutions to help students with concerning behaviors. It starts with gathering information from students to understand what is making it difficult for them to meet certain expectations and engages kids in the process of solving the problems that affect their lives.

After generations of a punishment-based status quo, this approach may sound unrealistic. But this evidence-based model has been shown to dramatically reduce the use of restraint and seclusion and to reduce or eliminate discipline referrals, detentions and suspensions. And the three stimulus bills Congress passed to provide $190 billion in new school funding in 2020 and 2021 could help educators with the resources and training to break the chains of the punitive, exclusionary disciplinary strategies that have been the mainstay of behavior management for generations.

Many schools no longer use detentions, suspensions, restraints, seclusions and corporal punishment. They’re still safe. Their students are not out of control. All kids — especially the ones struggling the most — deserve an approach grounded in empathy and evidence. Getting there will have far more to do with collaboration than consequences. All those problems that didn’t get solved before school let out will still be there when they return.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)