Gimbel & Suilebhan: The Banning of ‘Maus’ Is Only the Latest Echo from the Rise of the Nazis. We Cannot Claim to Not See the Warnings

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

Correction appended

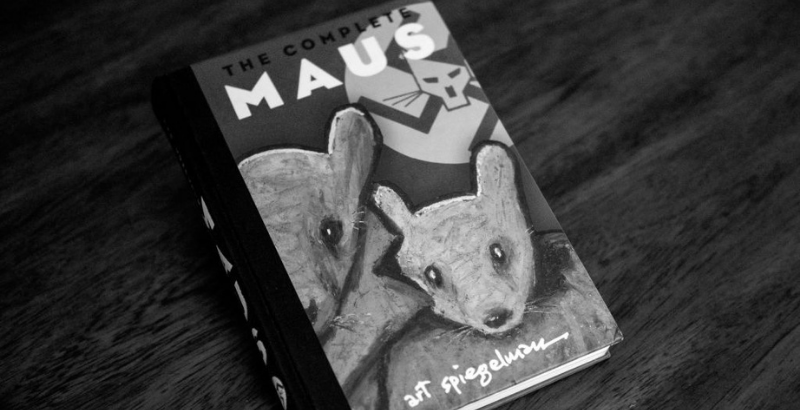

On Jan. 10, the school board in McMinn County, Tennessee, voted 10-0 to remove Maus from the eighth-grade history curriculum. The book, a graphic novel by Jewish American cartoonist Art Spiegelman depicting the grim realities of the Holocaust, expressed the absolute inhumanity of what happened in clear terms that children could understand.

As the child of Polish-born parents who lost much of his own family to the Holocaust, Spiegelman understood the gravity of the subject matter and committed himself to one clear idea: “Never again.”

To its great shame, the school board argued the book contained objectionable language and was unsuitable for use in the classroom. Despite pleas from history teachers concerning the importance and effectiveness of the work, the conservative school board chose to diminish its own school community’s understanding of the horrors of Nazism. Ironically, it did so by taking a tactic directly employed by Nazis themselves.

In 1933, German logician Olaf Helmer was busy writing his doctoral dissertation in the mathematics building at the University of Berlin when he looked through a window and noticed a group of thugs building a bonfire, then hurling library books into the flames. He immediately knew whose books they were, but the thugs confirmed his worst fears. He heard them shouting “I condemn to the flames the work of the Jew.”

Helmer — who one of us interviewed two decades ago, when he was 94 — escaped Germany in 1934, emigrating to America to become the assistant to a logician at the University of Chicago. He worked for the Air Force and became an American citizen, and in 1968 he co-founded the Institute for the Future, a nonprofit think tank. Still, he never shook the memory of losing family in the Holocaust. He drew a straight line from books thrown into bonfires to bodies burned in ovens.

Personal interviews with others who, like Helmer, managed to escape the Nazis, revealed similar haunted memories. Survivors have trouble using words to describe a society being taken over by genocidal hatred. They often rely on understatement, accented with sarcasm, and Helmer was no different. “It was very unpleasant,” he said, “the last year there.”

As scholars who studied the period, we knew the horrors that Helmer and the others were hinting at. As adults, we could read the pain beneath their sarcasm. Children, however, struggle to recognize such cues, and as a result, struggle to understand that such evil is possible. Spiegelman’s answer to that dilemma was Maus.

If the Tennessee school board’s ban had been an isolated incident, perhaps it might be dismissed as a localized example of overzealous language policing. Sadly, it’s merely the latest in a string of concerted censorship efforts targeting the actual history of people who suffered at the hands of white Americans and Europeans. It belongs alongside recent opposition to the 1619 Project, which chronicles the collective sin of American slavery; the attacks on the teaching of critical race theory, which has nothing to do with critical race theory and everything to do with not allowing critical thinking about race in America; and the “don’t say gay” laws recently proposed in Florida.

We all saw the photographs of the January 6 insurrectionist proudly wearing a “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt. We all heard the Charlottesville protesters chanting “Jews will not replace us,” just before being called “very fine people” by the then-president. We’ve all seen the right-wing meme depicting a murdered man of color above the abhorrent caption “Black Lives Splatter.” We‘ve all seen postings by militia members calling for a race war in America, listened to Reps. Marjorie Taylor Green and Lauren Boebert echo the call for “a Second Amendment solution” and watched Rep. Madison Cawthorne take out and clean his handgun during an online House Veterans Affairs Committee hearing.

Worse still, the former president has signaled his approval of the insurrection. Most recently, at a rally in Texas on Saturday, he said, “If I run and if I win, we will treat those people from Jan. 6 fairly,” he noted. “And if it requires pardons, we will give them pardons.” He also decried investigations into his business practices and possible election tampering — all headed by African-American prosecutors — as “racist,” fanning the flames of right-wing racial grievances. The same weekend saw a neo-Nazi rally in Orlando, complete with Hitler salutes and signs reading “Vax the Jews,” vandalism at a Chicago synagogue and swastikas scrawled all over Union Station in Washington, D.C.

This, we fear, is what Olaf Helmer saw coming in Germany. This is the looming horror that Art Spiegelman tried to depict for children, and for us all. We cannot claim to be unable to see the warnings. They are right here.

Helmer noted that he saw right through the Nazi charade at the bonfire. Afterward, you could still find copies of the books they burned — works by Albert Einstein and other Jews — in the university library. “They were very careful,” he said, “not to burn the last copy.” The Nazis may have been evil, but they were not so stupid as to destroy their own access to knowledge. As for our homegrown nationalists here in America, we should be worried that they will.

Correction: The slogan on the January 6 insurrectionist’s sweatshirt said “Camp Auschwitz.”

Steven Gimbel is professor of philosophy and affiliate of the Jewish studies program at Gettysburg College. Gwydion Suilebhan is executive director of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation and project director of the New Play Exchange for the National New Play Network.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)