‘Fulfilling the Mission’: More Than 70 New Mexico National Guard Members Step in as Substitute Teachers to Keep Schools Open

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Sgt. Lee Allingham, 32 and a member of the National Guard, was so upset by the notion of kids staying home from school because of the teacher and substitute shortage gripping his home state of New Mexico that he knew he had to help.

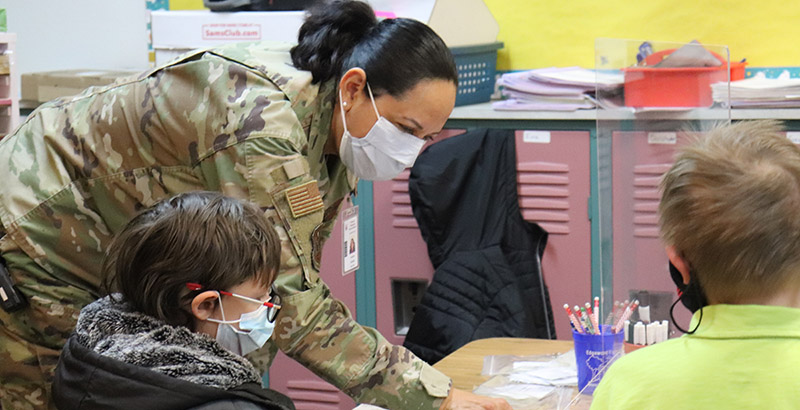

Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham gave him just that chance on Jan. 19 when she called upon both state workers and the Guard to alleviate personnel shortages on school campuses and inside child care facilities. More than 150 volunteers applied to participate and 94 substitute teacher licenses have been issued. On Feb. 1, 73 Guard members were serving in New Mexico classrooms.

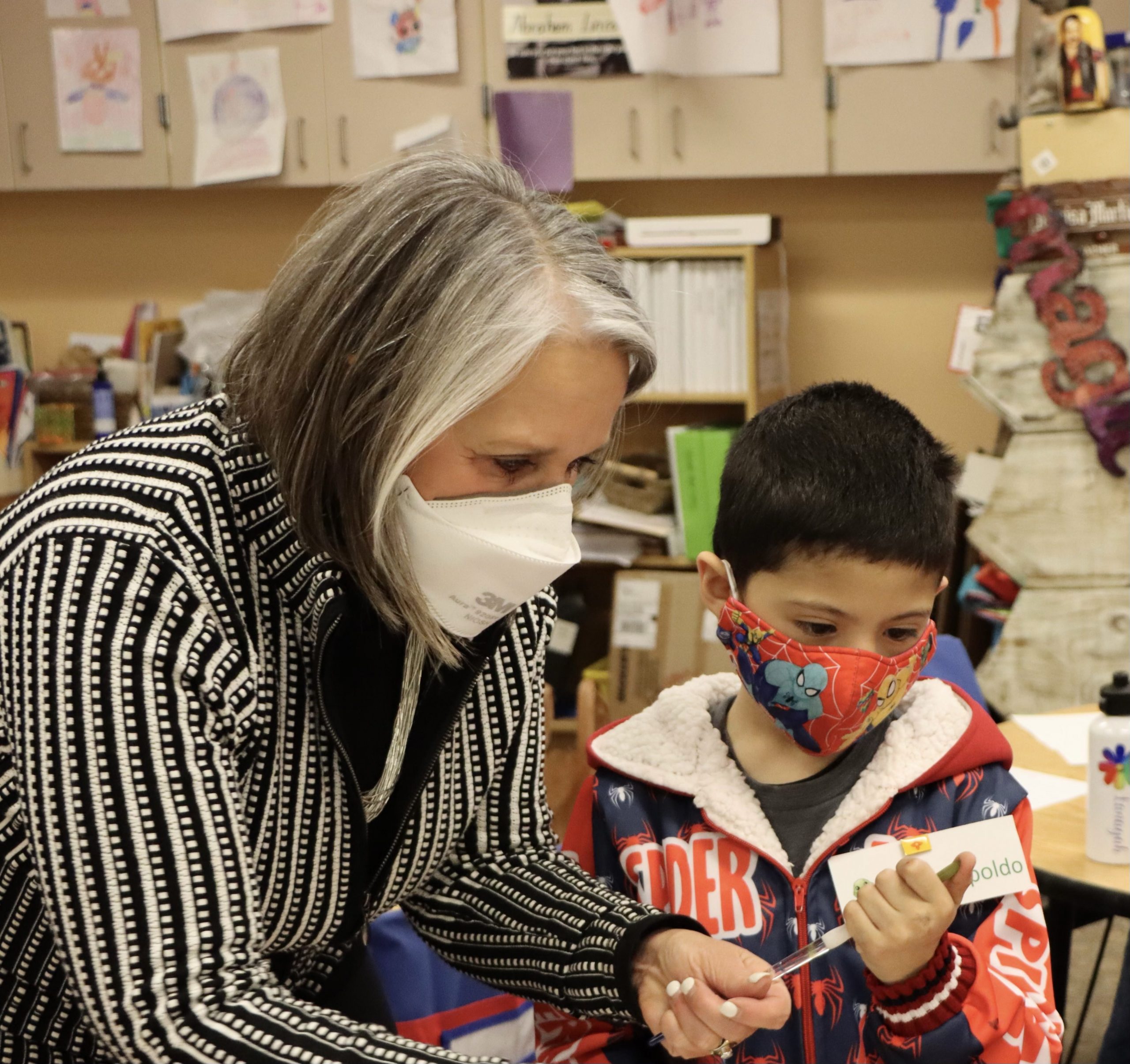

Volunteers began their service the week of Jan. 23 in more than 20 school districts across the state, according to the governor’s office: Grisham is so devoted to the cause that she worked as a substitute for a group of kindergarteners at Salazar Elementary in Santa Fe in late January.

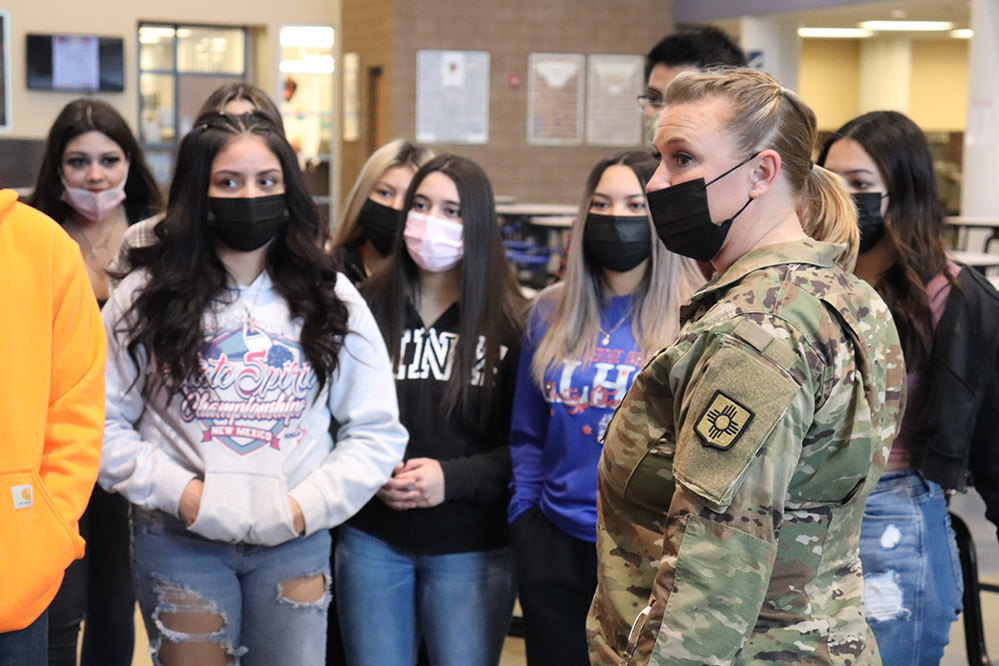

New Mexico was the only state to request Guard education support as of Feb. 1, according to a spokesperson for the organization who added the mission is currently funded until Feb. 18. Guard members have been called upon to drive school buses in at least 11 states, but not to teach. Uniformed police filled open classroom slots in Oklahoma.

While Grisham’s request was unusual — the Guard more typically helps with domestic crises and in support of active-duty personnel abroad — her problem is not unique. Several Ohio and Michigan schools closed last month because of staff absences and at least one district in New Jersey will end early every day in February at the middle and high school level because of substitute shortages.

Burbio, which tracks school closures, reported 7,461 schools actively disrupted — meaning they were not offering in-person learning — on at least one day during the week of Jan. 10. The number went down to 2,103 two weeks later but the issue remains a concern.

Some 60 New Mexico school districts and charter schools moved to remote learning since winter break, the governor’s office announced, and 75 child care centers have partially or completely closed because of staffing shortages since Jan. 1.

Allingham has spent much of the last two weeks working at a school district in Las Vegas, New Mexico, where he grew up. He knew small communities like his were particularly hard hit and asked for the assignment, traveling some 90 minutes from his home in Rio Rancho, just north of Albuquerque, to fulfill the mission. He knows many of his students’ families, having gone to school with them years back.

“It pains me to see kids getting a lack of education, to see them miss out on opportunities because of the pandemic,” he said. “I know it probably frustrates them as well when a favorite teacher has to go out for COVID.”

Allingham knows his knowledge of the classroom doesn’t stack up against former teachers or veteran substitutes, but he’s glad to fill the role, calling upon his own education and work experience whenever needed: His criminal justice degree and years in law enforcement proved helpful for a group of high school students studying Miranda rights.

“Based on my experience I asked, ‘Do you know what happens if you guys were to get arrested?” he said, adding he told students to be cooperative but to remember their own civil rights.

Allingham, like the rest of the state’s volunteers, had to adhere to the same standards as all other substitute teachers, submitting to a background check and completing an online workshop before setting foot in a classroom.

Not everyone around the country was thrilled at the prospect of outsiders entering schools for the first time. Critics from both parties pushed back on what they call a temporary fix, with one Democratic politician from Oklahoma saying they felt the call for volunteers devalued the teaching profession. But, in the face of widespread school closures, other educators have embraced the development.

Adriana Cuen-Flavian, a teacher at Santa Teresa High School in the Gadsden Independent School District and a union representative for her campus, said she’s glad for the Guard’s help. Out sick with COVID in late January, she’s well aware of the absences caused by the pandemic. She said she prefers the Guard to some of the substitutes her district has hired to keep the doors open, including 19- and 20-year-olds.

“They don’t have the life experience or professionalism … to be a responsible teacher in the classroom, where a member of the National Guard probably does,” she said.

Principal Jeff Hartog of Katherine Gallegos Elementary School, part of Los Lunas Public Schools, about a half hour south of Albuquerque, has been struggling for months to keep kids in school. Last week, between 180 and 220 children — of a total 620 students — were absent each day, in part because he reverted the sixth grade to remote learning after several teachers tested positive for COVID.

Hartog is hard pressed to find substitutes: He recently filled in for a music class though his training is in mathematics. He’s already called upon Lt. Col Aysha Armijo to assist when staff was too thin. Armijo, the task force commander for the substitute teacher initiative, had worked as a sub for several years and also as a cheer coach for the high school.

“Having her in the building was no issue at all,” he said. “My teachers do a good job with sub plans and I know our personnel department vets people pretty well.”

Staff Sgt. Armando Heras, 39 and who works at a juvenile detention center, was compelled to volunteer in the state’s public schools because he was worried about those children who might get into trouble if left home alone. At 6 feet 3 inches tall and 250 pounds, this Guard member is a commanding figure inside the classroom.

“The kids see me and think I’m a giant,” said Heras, who is working at Koogler Middle School in Aztec, New Mexico, nearly three hours northwest of Albuquerque. “Last week, they attempted to run all over me, but this week they know who I am. They feel my presence … and they are on their best behavior.”

Heras subbed for a physical education teacher last week and is overseeing art classes this week: one class is sketching the human eye. Their new substitute isn’t a trained artist but helps wherever he can. Mostly, he’s just glad to keep kids in school and to prevent overcrowding when students are added to other teachers’ classrooms.

“If I can be here to relieve that pressure, I’m doing my part,” he said. “We are supporting our state, our teachers, our communities. We were called upon by the governor to volunteer. If we can support the teachers and help keep the school doors open, we are fulfilling the mission.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)