‘Falling Through the Cracks’: Enrollment Drops in Cleveland Schools as COVID-19 Pushes Kids Online and the District Starts Hunt for Kids

Enrollment in the Cleveland school district is down about 4 percent this fall after COVID-19 forced classes online to start the school year, Cleveland school officials reported this week.

The district is trying to sort out why enrollment fell by 1,500 students. Most of the drop comes from preschool and kindergarten, where students likely never enrolled to start school. That fits a trend that has been showing up in cities across the country.

But the district is just starting to investigate whether other missing students have moved, enrolled in private or charter schools, or just dropped out.

Data shared with city education leaders and the school board this week show that the district’s enrollment has dropped from about 36,900 last school year to about 35,400 today, with online classes now in their third week. Attendance online has been lower than last year, with some schools doing well and others with less than 70 percent of kids participating in class.

“I’d like it to be better,” district CEO Eric Gordon told city education leaders this week. “But that’s where we are.”

School board members and city officials questioned Gordon in a series of meetings this week on how long it would take to determine where the students are and how the district is trying to find them.

“There’s really no way yet to know how many students are possibly falling through the cracks … through this virtual learning environment?” asked board member Kathleen Valdez.

Monyka Price, chief education aide to Mayor Frank Jackson, asked Gordon when the district would start visiting homes or tracking families down.

“We’re working on it,” Gordon told the board. “Here in the next week or so, we should have a much higher level of confidence about who’s actually showing up and regularly engaged and who we have to go find and get them engaged, or families that have actually chosen to go another place.”

He added: “I’m not naive enough to think that no one’s falling through the cracks … We’ve really been stressing with our schools, including the teachers union, the importance of tracking down and finding all these kids. What I am not yet confident in is, what is the number of those kids?”

Board members and city officials are worried that the spring shutdown, summer break and inability for students to return safely to classrooms has led some families to give up on school. It’s a real concern for a city that the U.S. Census just found to be the poorest and the worst-connected to the internet in the nation, and for a district that has one of the worst chronic absenteeism rates in Ohio.

Verifying enrollment takes time even when schools are open, Gordon said, because Ohio does not require families to notify schools when a child withdraws or attends another school.

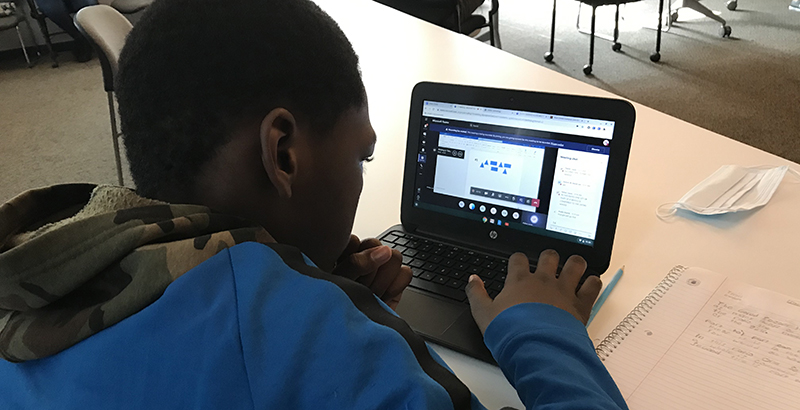

The pandemic also forced classes online this fall, a dramatic shift for a district that has struggled with digital literacy and for a city where 31 percent of households in the city have no internet access at all. The district bought and handed out 30,566 laptops and tablets to students, Gordon reported this week. When more than 6,000 arrived late, classes for many students were delayed a week or more.

The district also passed out 12,000 internet hotspots to connect families.

The district has now given devices and hotspots to almost all students that need them, Gordon said, so it can start tracking missing students.

The enrollment data Gordon shared this week are dominated by drops in the number of preschool and kindergarten students — two grades that Ohio does not require students to attend. Ohio law only requires school for kids 6 and older. Those grades also rely on families enrolling kids for the first time, so families cautious about school during the pandemic would show up in these numbers first. Preschool and kindergarten reductions also show families not ever starting their children in school, rather than students leaving.

Preschool enrollment of 2,000 students last school year has fallen to 773 this year. The kindergarten count of about 2,900 students last year dropped to 2,300 this year.

Combined, those two grades have 1,800 fewer students than last year.

”Many families are simply keeping their preschooler with them and will revisit school at a later time,” Gordon said.

That’s in keeping with what preschools across the city are seeing, said Debbie Fodge, the acting director of Starting Point, an agency that helps connect families to preschool. She said demand for preschool is lower this year, as many parents are keeping kids out of preschool for safety reasons or because they are out of work and at home.

Melissa Adipietro, a regional leader for the Ohio Association for the Education of Young Children, said preschools that are only online, as the Cleveland school district’s are right now, aren’t big draws, while in-person preschool that can solve the child care needs of parents can have waiting lists.

That drop could be a setback for a city that created a joint city, district, county and nonprofit coalition called PRE4CLE in 2014 to boost preschool attendance. The hope is that quality preschool can close kindergarten readiness gaps between affluent families and low-income ones in the city. More kids have been attending preschool since PRE4CLE started, but the drop breaks that pattern.

How much students will be hurt is still in question.

“We may not know for some time what all the outcomes will look like,” Fodge said.

For other grades, the district is looking at log-on data and attendance reports from teachers to see which students are participating in classes. Attendance reports provided to The 74 last week by the district show widely varied rates by school, with some schools showing well over 90 percent of students attending some days, while others show less than 70 percent. The district has averaged about 91 percent attendance the past few years.

The 74 has requested daily student log-on counts to see how many students are not just enrolled but at least connecting to classes, but the district has declined to share them.

Gordon estimated attendance in online classes at about 85 percent, though the district is still weighing how to count synchronous lessons — lessons given live online by a teacher — versus other work students do on their own schedule. Technical issues blocking students from connecting also skew the data.

“This week, we can anticipate sufficient stability, as we’ve got the system going, that we’ll be able to start to look for those kids that are really not connected and find out, is it that they’re there but not participating? Is it that they are enrolled somewhere else and we just don’t know it yet?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)