ESSA Analysis: Betsy DeVos Set the Rules for States’ New Education Plans, So Why Is She Blaming Local Leaders for Following Them?

Before she took on Lesley Stahl on 60 Minutes, and hostile members of Congress at an appropriations hearing, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos was confronting state education leaders.

In early March, DeVos used her invitation to address the Council of Chief State School Officers to sharply criticize states’ plans to implement the Every Student Succeeds Act for the first time. Her message was just the latest in a yearlong, (mostly) inside-the-Beltway debate about ESSA plans.

Democratic lawmakers publicly accuse DeVos of ignoring the law, while Republican leaders quietly put pressure on her behind the scenes to shape ESSA policy to their liking. Edu-pundits go back and forth in reports and blogs and on Twitter about whether the plans are good, bad, or ugly. Organizations representing states respond with their own public relations campaign, hashtag included, to defend states’ work and ideas.

With such a cacophony of opinions, it’s easy to forget how we got here: with the elimination of regulations to implement the law over a year ago, and a rushed process to replace them with a new set of expectations for state plans. And on this point, DeVos is more culpable for the contents of state ESSA plans than she cares to admit.

What a difference a year makes. Since her confirmation, the secretary has talked up her deference to states, indicating she would only focus on compliance with the law — not her own policy agenda. Last spring — at the same CCSSO meeting — she said, “As chiefs you are often the ones who sit down and figure out exactly how your states can maximize the freedom and flexibility given to you under ESSA…. The purpose of giving you that latitude is to ensure that all students have access to quality options for education.”

One of her first missives to chiefs about ESSA was even plainer: “One of my main priorities as secretary is to ensure that states and local school districts have clarity during the early implementation of the law. Additionally, I want to ensure that regulations … provide the state and local flexibility that Congress intended, and do not impose unnecessary burdens.”

DeVos promised that her department would treat states differently than when Obama education secretaries Arne Duncan and John King were in charge. In this light, DeVos’s “tough love” at the 2018 CCSSO meeting was a 180° — with a laundry list of specific ways in which state plans fell short:

● State accountability systems are too complex, inhibiting states from providing understandable and clear information to parents on annual report cards.

● States’ ideas for school improvement are uncreative — and unlikely to be effective.

● States are focusing too much on improving school systems, and not enough to directly support students in those schools (via school choice, course choice, tutoring, etc.).

● States are still relying too heavily on outdated modes of testing students each year that don’t encourage higher-order thinking and deeper understanding of academic content.

● ESSA requires states to report on per-pupil expenditures at the school level for the first time; states should do more to expose whether funds are spent wisely and equitably.

What DeVos didn’t say was that she determined what states had to include in their plans. As a condition of receiving funds from each large formula program in the law, like Title III for English learners, ESSA stipulates a lengthy set of requirements, descriptions, and assurances that states must submit to the federal department for approval.

However, the law also gives the secretary authority to establish a consolidated process for these plans, enabling states to submit a single document that covers all of the programs rather than drafting them one by one. Because the process is intended to be simpler and streamlined, the consolidated plan doesn’t have to include every detail in the law — the secretary picks and chooses what descriptions, information, and other materials are “absolutely necessary.” But the secretary must also take action to set up the process, estimate how long it will take and the burden it imposes, respond to public comments, and get approval from the Office of Management and Budget to collect the information from states.

When the Obama administration issued final ESSA regulations on accountability in November 2016, the notice-and-comment rulemaking process also established then-Secretary King’s determinations of what was “absolutely necessary” to include in a consolidated state plan under ESSA. This state plan template was published a few days after the regulations, and guidance for peers who would be reviewing them followed in January 2017. The department also published guidance and FAQs explaining the law and the new regulations for accountability, school improvement, and reporting. All of this information — taken together — was intended to give states a clear indication of what the feds would be looking for once they submitted plans in the spring and fall.

What many don’t realize is that when the ESSA regulations were repealed by Congress three months later — with support from the Trump administration — the ESSA plan template became null and void as well, a mere month before the first plans were due. In order for states to submit a consolidated plan at all, DeVos’s team had to scramble to establish a new template and determine what, in their view, was now “absolutely necessary.” The timeline was so condensed that she had to use emergency provisions in administrative law to do it — bypassing the typical public comment process.

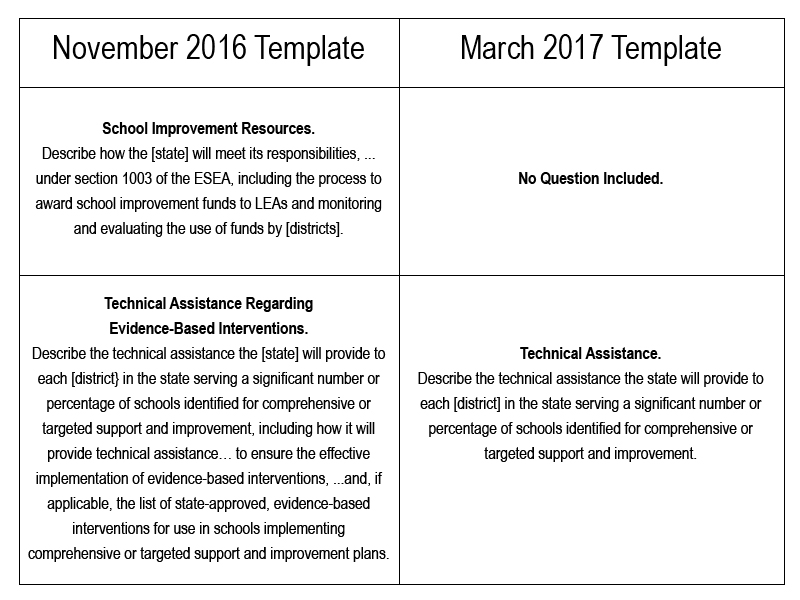

Here’s where DeVos’s criticism of state plans rings hollow: She wasn’t a bystander; she controlled the process. She could have included questions on the very items she finds lacking in state plans, but she chose not to. In some instances, she deliberately removed questions on those topics. Just compare the November 2016 questions to those DeVos asked on school improvement funding and evidence-based interventions, one of the items on her list:

The question on technical assistance in the new template is much more generic, removing any reference to evidence-based interventions. In fact, the word “evidence-based” no longer appears in the template at all, despite being defined explicitly in ESSA and referenced 54 times. It’s such an important provision that Congress just called out the evidence requirements in the bipartisan funding bill. And the question about how states will allocate school improvement resources? The 7 percent Title I set-aside she scolded chiefs about? Completely removed.

Likewise, if the provision of direct student services is such an incredible opportunity, DeVos could have included a question about it on the template — raising the profile of states’ new flexibility to set aside 3 percent of Title I dollars without adding to the overall burden of the plan or adding onerous regulatory requirements. DeVos chose not to. It’s unclear how she’s even certain only two states are pursuing the opportunity when the department didn’t ask them directly.

Why does this matter? Because only the questions DeVos required states to answer were reviewed by the peers and her team. States could go above and beyond the template and submit more to the feds — as some have encouraged — but there were strong disincentives to do so. Drafting a more robust plan could require extra staff time and resources within state agencies, invite scrutiny and political pushback from local stakeholders on items that weren’t even necessary to include, and raise potential red flags for future federal monitoring (if the department ever decides to take a look at what the state was doing in the additional areas). It’s hardly surprising states submitted exactly what was asked of them — and nothing more.

The template is but one example of how, time and again, DeVos has set the bar low for state plans. Not only is her template bare-bones, at best, but also the department has failed to issue any significant policy guidance on what the law requires and how it’s being interpreted as she approves the plans. Believe it or not, guidance is usually published as an official document — not emailed to intrepid reporters trying to figure out whether Democrats’ criticisms of ESSA plans DeVos approved are justified.

Non-regulatory policy guidance could not only provide information to frustrated members of Congress but also answer states’ questions as they struggle to make meaning of new requirements and convoluted language. And guidance can highlight opportunities in ESSA for states to better support students and families. For instance, the Obama administration released guidance on state report cards — another item on the list — including suggestions for how states could ensure school information was understandable and digestible for families despite the number of new reporting requirements. It even included a mock-up of a possible report card. Instead of directing her team to fully update the guidance to reflect the repeal of the regulations, however, it now begins with this giant disclaimer, full of legalese:

“Under the Congressional Review Act, Congress has passed, and the President has signed, a resolution of disapproval of the accountability and State plans final regulations that were published on November 29, 2016 (81 FR 86076). Because the resolution of disapproval invalidates the accountability and State plan final regulations, the portions of this guidance document that rely on those regulations are no longer applicable. To the extent that this document addresses statutory requirements, however, it is unaffected by the resolution of disapproval.”

Translation: Think twice about using this document.

Secretary DeVos has a vastly different view of the federal role in education than her predecessors. It’s unsurprising she’d seek to scale back federal regulations — and the department itself — and streamline requirements. But she’s also refusing to use any of the other, more subtle tools at her disposal to help states implement ESSA and use its new flexibilities, like issuing guidance, seeking additional funding for technical assistance, or simply asking states direct questions about what they are doing. These tools don’t limit what states can do — they support them.

Instead, DeVos turns to the bully pulpit, first to talk up her belief that those closest to students — parents and local policymakers — should be empowered to make policy decisions, and then to chastise them for making the wrong ones.

Secretary DeVos — not states, not the Obama administration, and not Congress — made the rules for what has to be in a consolidated state plan. She shouldn’t cry foul when states follow them.

Anne Hyslop is an independent education consultant and former senior policy adviser at the U.S. Department of Education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)