Drool-Worthy: As Biden Urges More COVID Tests, Quick and Inexpensive Saliva Screening is Raising Hopes for a Less Disruptive School Year

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

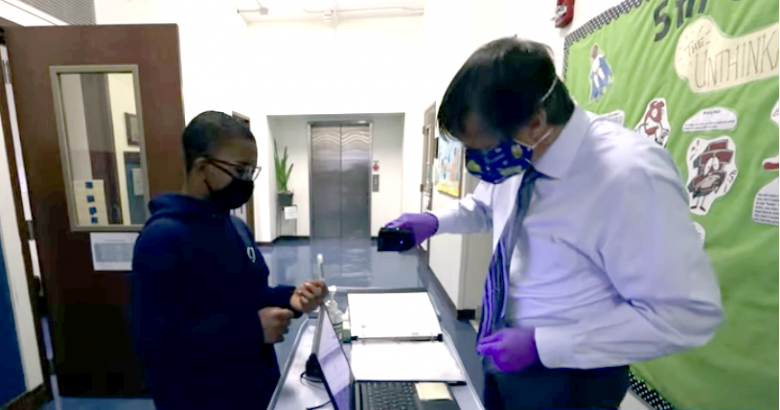

A new breed of fast, cheap, and, in most cases, accurate new COVID-19 tests could remake the fraught debate over virus outbreaks at school this fall. Using subjects’ saliva instead of invasive nasal probes, they promise to help schools test more people, quickly find and isolate positive cases, and return students to the classroom once they test negative.

Whether schools can roll tests out effectively — and get cooperation from those who screen positive for the virus — remains to be seen.

The promise of quicker, more accurate results could bring a welcome reprieve for school districts across the country that are sending large groups of students home with suspected COVID exposure. Last month, six days into the school year in Florida’s Palm Beach County, one in 50 students was forced to quarantine. In California, state guidelines call for unvaccinated students who are “close contacts” of a person with a positive COVID test to stay home for 10 days, forcing thousands of students too young to get a vaccine to miss critical days of in-person instruction.

While the tests’ use in schools has only recently begun to rise, the technology has been in development, in many cases, for more than a year. One of the new tests, developed by Yale University, is available through a network of about 85 labs nationwide and counts the National Basketball Association among its users. Another test, developed at Rutgers University, has been championed by New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy, who last year called it a potential “game-changer.”

In the K-12 world, the saliva test with arguably the most traction is one developed by the University of Illinois — it is in use by about 45 percent of the state’s 3,859 K-12 schools, covering more than 877,000 students, the university said. School health officials elsewhere, including Baltimore and Washington, D.C., are also piloting it, with more districts likely to follow.

The field will likely get a huge boost after President Biden last week committed to offering nearly $2 billion for schools, community health centers, and food banks to buy about 300 million rapid tests. Biden said he’d use the Defense Production Act to increase the manufacturing of rapid tests, including those that families can use at home.

‘A very promising platform’

Researchers developed the Illinois test in June 2020, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorization for the so-called covidSHIELD test in February. One reason researchers say saliva tests work better is that virus found in the saliva is more likely to have passed into patients’ lungs, where it can do serious damage. Viral load in saliva, they say, is also significantly higher in patients with known COVID-19 risk factors, such as obesity or diabetes.

Because the new saliva tests are polymerase chain reaction or PCR tests, they can detect both the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19, as well as fragments of the virus after a test subject is no longer infected.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Smith, a University of Illinois infectious disease epidemiologist, developed the studies that earned their test its emergency authorization. She said PCR tests are not only reliable, but very sensitive. And they’re better early-warning indicators of infection.

“Our data show that saliva is one of the best ways to find people early because the virus replicates in saliva before it moves to the nasal tissues,” she said.

But saliva tests aren’t without controversy. In one case earlier this year, the FDA warned that a saliva swab test developed by the California startup Curative risked missing some later-stage infections. It said Curative’s tests should only be used on people who showed COVID symptoms within the prior two weeks.

In January, health agencies in Colorado, citing concerns over false negatives, said they planned to phase out the Curative tests. Other purveyors have tried to distance themselves from these results.

Dr. Tim Lahey, an infectious diseases physician and head of ethics at the University of Vermont Medical Center, said he’d reviewed research with a small sample of patients on the Yale test, as well as a meta-analysis for other saliva tests. Research on the Yale test, he said, found that saliva in the samples was as accurate as nasal swabs. And the meta-analysis, he said, “showed basically the same thing for various saliva testing approaches including the one developed at Yale.”

But he cautioned that he hadn’t seen detailed analyses of “how well the saliva technology performs in people with mild symptoms, or no symptoms at all.”

And the Yale sample was small — just nine patients. How well the test performs in larger groups “is still an open question.” But he said it’s “a very promising platform” and he’s looking forward to seeing more data.

Lower cost, faster turnaround

Pinpointing exactly how many K-12 schools regularly test students for COVID-19 is difficult, but a few indicators suggest that testing isn’t widespread. A recent RAND study found that the largest group of schools implementing testing last fall were using rapid tests mostly for symptomatic students and staff, “since they often lacked enough tests to conduct screening testing.” Private schools were more likely to be conducting routine screenings, they found. One survey noted that about 20 percent of private K-12 schools conducted regular screenings at school.

The Illinois test costs just $20 to $30 per dose, a fraction of the typical $100 cost for a standard nasal swab test, according to SHIELD Illinois, the nonprofit that manages testing in the state. The organization is making it available for free to districts across the state, mostly thanks to $10 billion in federal COVID test funding for schools.

Beth Heller, a spokesperson for SHIELD Illinois, said the organization operates seven labs statewide, which cuts test turnaround time from as much as three days to less than one, on average.

A shorter turnaround time matters, especially now: With the earlier COVID-19 variants, Smith said, about 30 percent of infections happened before subjects showed symptoms. “With Delta, it’s more like 75 percent.”

In Baltimore, where school health officials have been using the Illinois-developed test since March, weekly saliva testing has “made parents feel comfortable sending their children back” to school, said James Dendinger, interim director of COVID testing.

In most of the district’s middle and high schools, students now submit to weekly saliva tests. In most elementary schools, health officials test classroom groups with nasal swabs. If any group of swabs delivers a positive result, they test each student again. Only those who test positive or who had close contact with those who test positive must quarantine.

These protocols kept Baltimore’s positivity rate extremely low last spring: from March 1 to June 15, it was 0.6 percent in middle schools and high schools, and less than 0.3 percent in pre-K-8 schools.

The new tests also bring a certain comfort factor, Illinois’ Smith said. “It’s a lot easier to drool into a tube than to have a swab stuck up your nose, especially if you’re going to be testing regularly.”

Laura Wand, an advisor for SHIELD T3, the for-profit that administers the tests outside of Illinois, said that ease allows users to make testing part of their routine. “The key to containing the virus is to be able to test often, isolate, and track,” she said. “And the gold standard for testing often is everybody, twice a week. Now, people are not going to do a nasal swab twice a week.”

For the SHIELD test, subjects let saliva pool in their mouth and simply raise a small funnel to their lips, then “let the saliva fall out, push it out with your tongue,” Smith said. “Once people get the hang of it, most people can complete the process in one to two minutes.”

One drawback: Test subjects can’t have anything in their mouth for at least an hour before the test, “which requires planning and logistics,” especially in K-12 schools. Students can’t eat or drink, chew gum, use mouthwash, or brush their teeth for at least an hour prior to the test. For adults, that means no smoking or chewing tobacco either.

Smith said the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, the system’s flagship campus, relied on the test for the entire academic year, at least for the more than 35,000 students attending class in person. “We did have some outbreaks, but they came in back under control,” she said.

The biggest one came early, between Aug. 15 and Sept. 15, 2020, as students returned to campus. In early September, the university even imposed a brief lockdown, The New York Times reported, after an unexpectedly high number of students with positive results continued to socialize and attend parties. One official called the phenomenon “willful noncompliance by a small group of people,” and top officials circulated a stern warning, saying the irresponsible students “have created the very real possibility of ending an in-person semester for all of us.”

The letter concluded, “We stay together. Or we go home.”

Behind the scenes, though, the university was testing so often, Smith said, that “we didn’t have to have a long-term lockdown” like other universities.

Willful noncompliance notwithstanding, the university’s seven-day average positivity rate never rose above 1.21 percent, according to data on its COVID testing website.

Once the twice-weekly testing got underway, Smith said, this “just brought everything back under control. We saw outbreaks within dorms or within apartment buildings, and we would increase the frequency of testing to every other day. And within a week we would bring the case numbers in that location down to zero.”

SHIELD Illinois’ Heller said the testing regimen has allowed Champaign County, where the flagship campus is located, to keep its COVID positivity rate under 1 percent since September 2020. Elsewhere in Illinois, she said, positivity rates jumped as high as 12 percent last fall. Nationwide, positivity rates climbed to about 13 percent last winter.

The state health department in August said it would offer the test for free to any school district outside of Chicago that wanted it (The city receives a separate federal funding stream that other districts don’t.) The department also said schools could use it to take advantage of a so-called “Test-to-Stay” protocol, rather than quarantine.

Under the protocol, students and teachers who have close contact with someone who tests positive can stay in school if they agree to be tested four times: one, three, five, and seven days after exposure. If their tests remain negative, they don’t have to quarantine.

Quick results bring ‘an extra layer of comfort’

One of the first public school systems to take up the SHIELD tests was the tiny Hillside District 93, a pre-K-through-8 district in Cook County, about 20 minutes west of Chicago.

Superintendent Kevin Suchinski said the quick test “allowed us to make sure that we kept our doors open” and avoid shutting down, even as other districts took drastic steps to control outbreaks.

And as in many areas, COVID cases there are rising — last week, the average daily new case count hovered around 1,000 per 100,000 people, but the county’s infection rate remains among the lowest statewide.

The ease of testing students’ saliva, he said, meant “we were testing early-childhood kids all the way up to 8th grade,” ages 3 to 13. The quick results, even with asymptomatic students, “gave us an extra layer of comfort to say, ‘Is it spreading within our community? Is it spreading within our school?’ And we could then react.”

Suchinski made the tests voluntary for students and staff, but the ease of testing and the district’s 0.5 percent positivity rate encouraged more people, including students’ family members, to submit to it. In August, the district was testing 55 to 60 percent of families.

“Nothing’s 100 percent,” he said. “We cannot guarantee that we’re going to stop [COVID]. We’re not going to stop cases. What we’re going to do is prevent the spread.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)