Districts Are Receiving Billions for Academic Recovery, But Some Parents Struggle to Find Tutoring for Their Children

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Aida Vega’s daughter ended middle school last year with two D’s — grades that left her feeling discouraged and self-conscious about being an English learner.

When her daughter entered Huntington Park High School in Los Angeles this fall, Vega asked if tutoring was available, but was told only students with F’s or a teacher’s referral were eligible.

Vega picked up extra shifts cleaning offices on nights and weekends to pay the $470 a month to get a private tutor. She wonders, however, why that was necessary: The Los Angeles Unified School District is receiving $2.6 billion in federal relief funds through the American Rescue Plan — 20 percent of which has to be spent to address learning loss, according to the law.

“The district is really …concentrating on people getting their vaccines,” Vega said in Spanish through an interpreter. “Let’s let doctors and pediatricians do their job and focus on that. The district needs to focus on learning loss and getting to a good academic level.”

Under the law, tutoring is just one way districts can address learning disruption caused by the pandemic. But with research showing that so-called “high-dosage tutoring” can provide struggling students the academic boost they need, both parents and policymakers expected to see districts use relief funds on such programs.

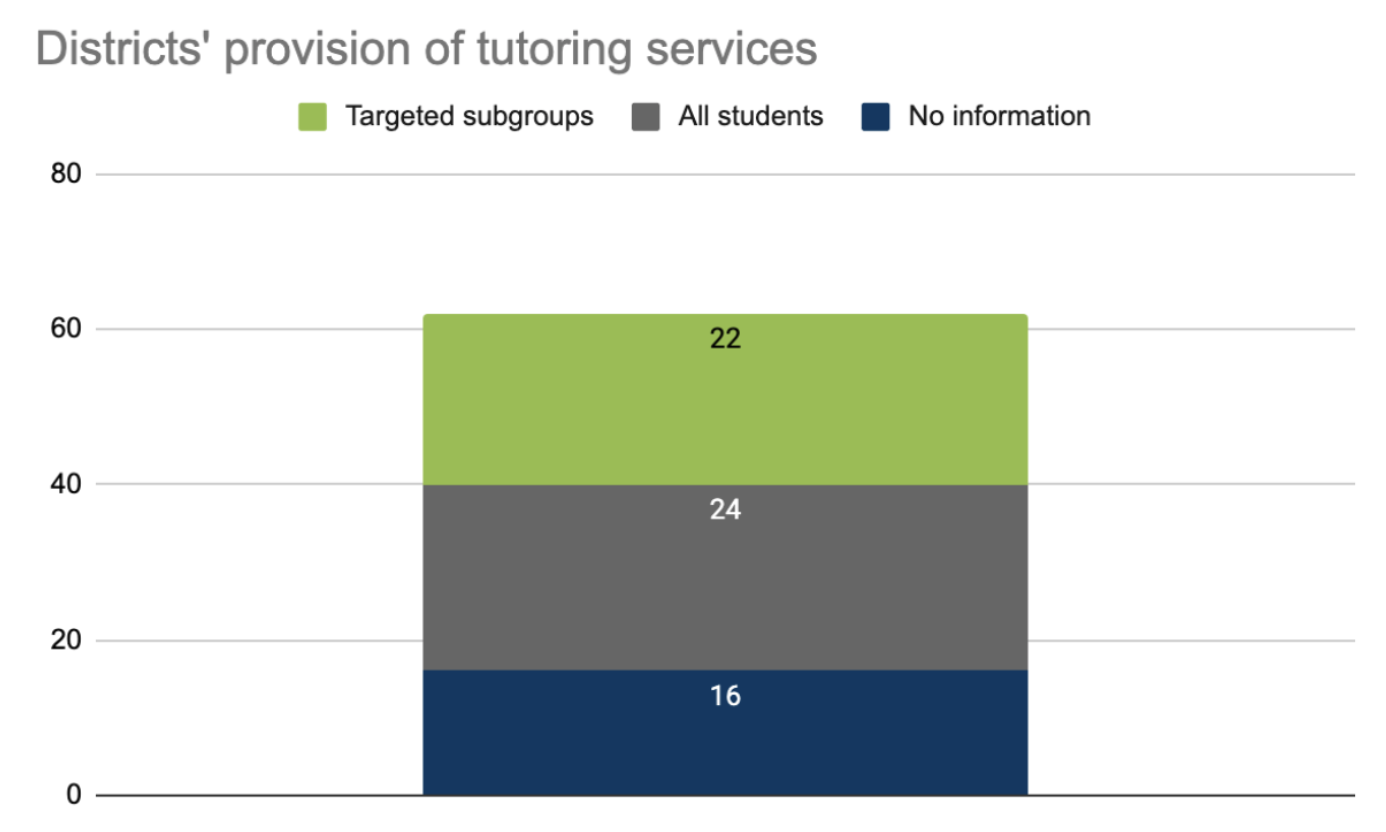

Thus far, however, the enthusiasm over tutoring has not translated into widespread adoption. A recent analysis from Burbio, which tracks schools’ responses to the pandemic, shows that out of 1,037 districts nationally, only about a third are spending federal relief funds on tutoring. The Center on Reinventing Public Education’s ongoing review shows that while 62 out of 100 large districts offer tutoring, most don’t provide details on their programs and how many students they serve.

Some districts have addressed learning loss by lengthening the school day or providing small group instruction. Others that have launched tutoring programs either restrict services to specific students or limit the number of sessions available. A shortage of available tutors has only exacerbated the problem.

“There is good research that high-dosage tutoring has really transformative potential and it’s also true that school systems are struggling mightily to meet the demand,” said Mike Magee, CEO of Chiefs for Change.

In October, another Los Angeles Unified parent, Ada Mendoza, was offered tutoring for her two youngest children twice-a-week at Manchester Avenue Elementary School. One hitch: It only lasted a month.

She signed them up, but had doubts that a month would be enough to make up for a year of distance learning. Eight-year-old Juan Jose was beginning to read when schools shifted to remote instruction, but now struggles with words of three or more syllables, reading comprehension and writing complete sentences.

Her children got the flu in October and missed some sessions. She said Juan Jose’s teacher told her he is still reading far below grade-level. “They lost a lot of learning, and they need a lot of help,” she said in Spanish through an interpreter.

According to the district, tutoring is available for children with disabilities, long-term English learners in grades three through eight, and foster, homeless and low-income students “based on performance indicators as identified by school sites.”

Mendoza said she can’t afford a private tutor, but some parents have gone that route. October data from the U.S. Census Bureau showed that 3 in 10 families with at least one school-age child had spent their first three monthly child tax credit payments on school-related expenses, including tutoring and afterschool programs.

“Guess we’re not all spending it on getting our nails done and filet mignon,” quipped Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union, an advocacy organization. The group’s recent polling showed that more than a third of parents consider not having enough tutoring or academic support to be a major or moderate problem.

The union has launched Everyday Parents Impacting Change — or EPIC — a “watchdog campaign” to follow the $122 billion K-12 schools are receiving through the relief bill. And in Los Angeles, Vega has joined other Los Angeles parents taking part in the nonprofit Innovate Public Schools, which monitors how the district is using relief money to help students get back on grade level.

Parent Revolution, another Los Angeles advocacy group, wants the district to create an “individualized recovery plan” for every student. Even if students can get free tutoring, it’s often a “blanket approach” that might not target their needs, said Jay Artis-Wright, executive director of the organization.

“We work with populations of families who have academic challenges that preceded COVID and now have a wider gap,” she said. “There is a surplus of funds that can support them, but only if we can agree that each child’s academic recovery is unique and should be treated as such.”

‘This giant puzzle’

Districts that have launched tutoring programs say they can’t serve everyone — especially as a tight labor market and quarantine requirements continue to fuel personnel shortages.

The Metro Nashville Public Schools, for example, has been able to sign up 500 tutors — a mix of teachers, paraprofessionals and community volunteers, said Keri Randolph, the district’s chief strategy officer. But that’s half the number they had planned to recruit, which means less than 1,000 students are receiving tutoring instead of the 2,000 the district expected to enroll through its $19 million Accelerating Scholars program.

The Delta variant, Randolph said, affected the size of the volunteer pool and she wasn’t as successful hiring retired teachers as she’d hoped.

The program — 30-minute sessions, three times a week for 10 weeks — currently targets low-performing first- through third-graders in literacy and eighth- and ninth-graders in math.

“It’s this giant puzzle,” Randolph said, adding that tutoring is “hot right now, but people have no idea how hard it is.”

Staff members at the 46 schools now offering tutoring manage the schedule so teachers aren’t “overburdened,” she said. The district tries to schedule the tutoring sessions during the regular school day to avoid the need for extra transportation.

But there are exceptions. Kindall Maupin, who has a daughter in eighth grade at DuPont Hadley Middle School in the district, was only offered a 7:30 a.m. slot for math tutoring — a time that doesn’t work because her daughter has ADHD and can’t focus that early in the morning.

“I feel like if they can have football practice and cheerleading practice at the end of the day, why can’t we do this then,” Maupin said. She added that she’s even considered refinancing her house to afford private tutoring. “I have been there, literally sitting down to crunch the numbers to see how I could do this.”

Maybe next semester

Experts said the current pressures on local districts affect whether they can pull off a new program on a large scale.

“Many educators are understandably exhausted from these past 18 months of school disruptions,” said Susanna Loeb, director of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University. “Implementing a new program — no matter how much funding is available for it or how much research supports its effectiveness — takes effort.”

Jonathan Travers, a partner with Education Resource Strategies, a nonprofit that helps districts address budgeting and staffing challenges, said many districts have contracted with vendors to give students 24-hour access to online homework help.

“We are trying to be clear that that is not the same thing” as high-dosage tutoring, he said, but added that with districts focusing on filling vacancies and managing quarantines, some are only now shifting to “actually putting canoes out in the pond around accelerating learning.”

That doesn’t stop districts from adding tutoring programs next semester, he said. And he added that some who are frustrated with the pace of implementation may push for districts to reimburse parents spending their own money on tutoring.

Marguerite Roza, director of Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, alluded to Travers’s idea in an op-ed this week, suggesting that districts share some of those federal funds with parents who are spending their own time and money helping students catch up.

“Given all the labor shortages, and the willingness to pay parents for driving kids to school, it is interesting that districts haven’t done more to go the route of paying parents to tutor their kids,” she said in an interview. “We thought we’d see some by now.”

Randolph, in Nashville, said she thinks her district needs to do a better job of communicating the other ways the district is spending relief money to address learning loss, such as funding $18 million for summer school and $6 million for computer-based literacy and math programs.

“It’s not just tutoring or nothing,” she said.

Still, she said leaders plan to continue tutoring beyond this period of recovery. That’s one reason why the district decided to build the program in-house, instead of contracting with a private provider, which can cost up to $4,000 per student for a year. That’s not a sustainable solution, Randolph said. The district is spending $400 per student for the 10-week period.

“We don’t think tutoring is just for a COVID response,” she said. “If it’s the right thing to do now, it’s the right thing to do later.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)