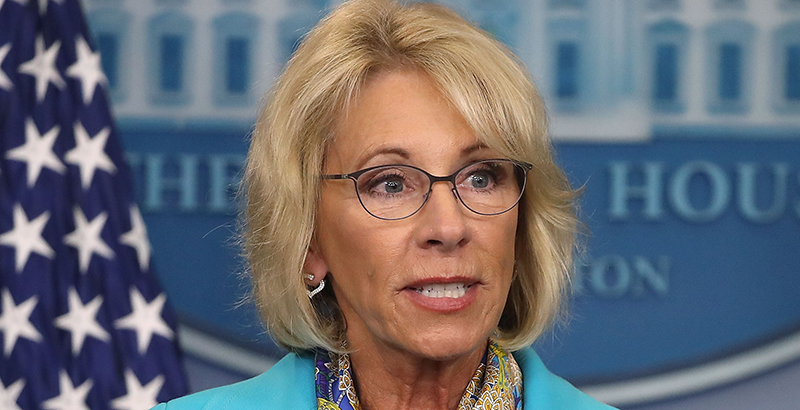

DeVos Rescinds Obama Sex Assault Rules, Allows Schools to Choose Proof Standard Until New One in Place

Updated at 4 p.m.

The Education Department has withdrawn Obama-era rules governing how schools handle allegations of sexual assault on campus, putting in place on Friday an interim Q&A document that advocates say could cause confusion on campuses in the coming months.

Crucially, the new Q&A allows schools to decide whether allegations of sexual assault will still be decided by the lower “preponderance of the evidence” standard the Obama administration required they use to prove accusations, or the “clear and convincing” evidentiary standard that is harder to meet. The rules implement Title IX, which bans discrimination in education based on sex.

“Nothing could be more devastating to survivors of campus sexual assault than to create uncertainty during the heart of the red zone during the school year,” Laura L. Dunn, founder and executive director of SurvJustice, a nonprofit that represents sexual violence victims, told The 74. The first six weeks of the fall semester are known as the “red zone” when freshman women and others new to campus are most likely to be assaulted.

DeVos announced earlier this month that she would overhaul the Obama-era guidelines, stressing the importance of due-process rights for students accused of sexual violence. “The era of ‘rule by letter’ is over,” DeVos said, arguing that the Obama-era guidance documents were “wholly un-American.”

The department’s move Friday withdraws both a 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter and a 2014 Q&A document on how to implement the new standards. The department “intends to” engage in a formal rulemaking process to write new rules, which could take months, department officials said.

By changing the standard as investigations are being conducted and cases are being adjudicated, the department has exposed “hundreds, if not thousands” of schools to potential lawsuits from students accused of sexual assault, Dunn said. “It’s almost like giving a free pass” to perpetrators of assault, she said.

“To say that it is thoughtless, I think, is the best thing that could be said. I think it is deeply harmful,” she added.

The Association of Title IX Administrators, in a lengthy statement to members, also warned of potential lawsuits.

“Schools would be wise to move slowly to make changes, given that anything in the interim guidance issued today could be changed in a year or so when new guidance is issued, making any actions in the interim potentially subject to challenge by those impacted,” Executive Director Brett Sokolow wrote.

Conservatives and advocates for the accused had taken issue with both the substance of the Obama rules and how they were issued — through a letter from the department rather than a formal rulemaking process.

“The campus justice system was and is broken,” Robert Shibley, executive director of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, said in a media release. FIRE, a nonprofit that promotes free speech and due-process rights for college students, sponsored a lawsuit last year that challenges the Obama-era guidance. “Fair outcomes are impossible without fair procedures. When the government sprang its 2011 letter on colleges and students without warning, it made it impossible for campuses to serve the needs of victims while also respecting the rights of the accused. With the end of this destructive policy, we finally have the opportunity to get it right.”

Given concerns with the previous administration’s approach to issuing the guidance, it would be “imprudent” to dictate evidentiary standards schools should use, either by setting a “clear and convincing” standard or keeping the Obama-era rules in place, until new rules are drafted, a senior Education Department official said on a call with reporters Friday.

“The impact over the last six years of the influence of losing sight of the importance of fairness and impartiality in these processes can be traced to the approach and substance of those documents. While rulemaking is pending, we couldn’t leave those documents in place while they were deeply flawed,” a second official said.

The department required reporters to identify three staffers on the press call as senior department officials rather than by their names and titles.

Boston College public policy professor R. Shep Melnick, who has written extensively on the need to reform the way schools are held accountable for sexual violence on campus and is a critic of the Obama-era guidance, said he doesn’t expect Friday’s announcement will prompt big changes from schools. Because the interim guidance could cause confusion for institutions, he said, he expects most will wait to see what is instituted through notice-and-comment rulemaking. Although he expects that process to take a year or longer, he’s optimistic.

“I think that this is long overdue, not just for these regulations but for all of OCR’s regulations,” Melnick said. “They have done this over and over and over on all kinds of really important matters, ranging from school discipline to school finance to athletics to transgender [rights]. If this is the beginning of a much more transparent, participatory process, that’s terrific.”

Uncertainty around the Education Department’s ultimate decision on Title IX mirrors to some extent confusion around the Trump administration’s recent decision to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, leaving questions for some 800,000 recipients about whether they would receive protections or face potential deportation.

The guidance released Friday also made other changes surrounding Title IX, namely removing a standard requiring that “prompt” investigations of assault allegations be completed in 60 days, and that “interim measures” put in place during investigations, like counseling, class schedule changes, or leaves of absence, be made available to all parties in a case.

“It really utterly failed in several areas,” Dunn of SurvJustice said of the DeVos announcement. “It’s using Title IX for the wrong purpose. Title IX protects those who were discriminated against on the basis of sex, not those who are doing that discrimination.”

Women’s rights groups and congressional Democrats also panned the move, as they did the announcement earlier this month, as moving backwards to a time when sexual assaults were “swept under the rug.”

Although the Title IX debate has focused in recent years on sexual assault and abuse on college campuses, the law also applies to K-12 schools. In fact, two U.S. Supreme Court rulings issued in the late 1990s, which set standards for when institutions can be held liable for failing to prevent student-on-student and teacher-on-student sexual violence, began in K-12 schools.

Public Justice Senior Attorney Adele Kimmel, who represents victims of sexual violence, said one part of the interim guidance will have a particular effect on sexual assault victims in K-12 schools. Among her clients with pending complaints is a young Georgia woman who says she was suspended after reporting an attack inside a Gwinnett County high school. A footnote in the DeVos guidance, she said, says K-12 schools are not required to tell victims whether the perpetrator was suspended or expelled from school.

“Anyone would want to know, ‘Am I going to be confronted on a daily basis at school by the person who sexually assaulted me?’ I think any victim would want to know that and should know that,” Kimmel said. “Every day you go, ‘Are they coming back today? Were they suspended for five days? Ten days? Were they expelled? How long do I have to be anxious and stressed about wondering whether I’m going to bump into this person at school?’ ”

The Education Department hosted a series of “listening sessions” in July to hear the perspectives of sexual violence victims, students who said they were wrongly accused, and school officials. The meetings were dubbed an opportunity for DeVos to hear all sides of the heated debate, and while much of the attention centered on colleges, K-12 students and officials also participated. Among them was the National School Boards Association, which hasn’t commented publicly about its role in the conversations. An association spokeswoman didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In August, a spreadsheet the Education Department provided The 74 showed the Office for Civil Rights was investigating 154 Title IX sexual violence complaints in 137 school districts. Those investigations, against public districts, private institutions, and charter school networks, spanned 37 states.

Any resolutions reached with schools under investigation will remain in place, according to the Education Department. Open cases will be “evaluated each on their own merits,” a department official said. If the only issues at stake are now moot after the withdrawal of the 2011 regulations (like a school’s use of the “clear and convincing” standard, for example), officials are likely to rethink that investigation, one of the department officials said.

New investigations also will continue during the interim period, officials said, emphasizing that nothing about the new guidance changes schools’ obligation to investigate complaints of sexual misconduct.

“I think it is going to cause a lot of confusion, more at the K-12 than at the postsecondary level because postsecondary schools have really been more proactive in trying to comply with Title IX’s requirements since the 2011 guidance was issued,” Kimmel said. “They’ve made greater strides than K-12 schools, so it’s just going to make things messier at K-12 schools.”

(More from The 74: Overshadowed by the college sexual assault debate, 154 open Title IX investigations at K-12 schools)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)