Detroit Boosts Civics Course by Including People of Color and Community History

The district says it is infusing local history and city government into civics classes, as well as promoting community engagement

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

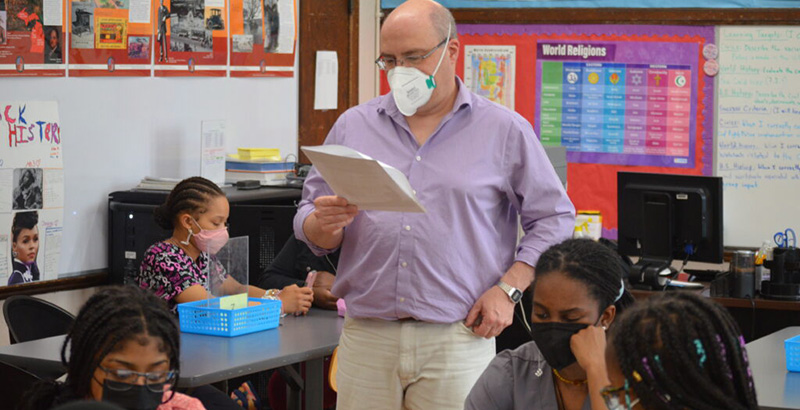

During a social studies class at the all-girls Detroit International Academy, 10th grade students last week learned about a historic student protest that occurred in April 1966 at Detroit Northern High School.

The students took turns reading passages via laptop computer and discussed the incident with their teacher on Wednesday. They learned that the Northern students, who were Black, were protesting what they described as inadequate educational resources at their school that had a white principal.

“The students refused to take that type of treatment,” said teacher Tal Levy. “Who wants to read the next paragraph called ‘student demands’?”

“Some of the demands were to remove the principal,” a student responded. “Remove the campus policeman, provide the information on the academic standards of the school, and create a student-faculty council for the school.”

The lesson is part of a new approach to teaching history at Detroit Public Schools Community District (DPSCD), the state’s largest public school district. For DPSCD, it is using a traditional approach of infusing local history and city government into its high school civics course — but with more cultural inclusion and promoting community engagement.

“The district’s mission focuses not just on education, but student empowerment and civic engagement,” said DPSCD Superintendent Nikolai Vitti.

Citizen Detroit partnered with the school district to revise its “Detroit: A Manual for Citizens,” a textbook that had not been updated in decades. The manual is available in both hard copy and electronic form and can be taught via laptop computers and tablets.

Citizen Detroit is a civic education nonprofit that “focuses on educating Detroiters about issues that are critical to our well-being; seeking to increase civic literacy; and working to establish a standard of public accountability from local and state elected leadership,” according to its website.

The Skillman Foundation, also a partner, helped to fund the effort, which took a little over two years to complete.

The manual and workbook were published in time for the 2021-22 school year and used in every high school civics class. Students spend about six weeks learning about local government.

“The idea is to give people a historical understanding of the function of city government and an understanding of each city department and how the citizens can be engaged, and their voices are heard,” said Sheila Cockrel, Citizen Detroit CEO and a former member of the Detroit City Council.

Civics is a stand-alone 10th-grade semester-long course that is a graduation requirement from the Michigan Department of Education. In Detroit, civics-related material is woven into every grade from kindergarten through high school as required by the Michigan Grade Level and High School Content Expectations.

Students learn about public policy issues and work to form their own opinions on those issues before they get to their civics class in 10th grade, according to Elizabeth Triden of DPSCD’s curriculum and instruction office.

Critical race theory

DPSCD’s bolstered civics effort preceded Republicans in Michigan and nationwide trying to ban critical race theory (CRT) in schools. CRT is a college-level theory that examines the systemic effects of white supremacy in America, but lawmakers have interjected the issue into the K-12 policy debate.

House Bill 5097, introduced by Rep. Andrew Beeler (R-Port Huron), does not explicitly reference CRT, but prohibits schools from teaching any curriculum that includes the “promotion of any form of race or gender stereotyping or anything that could be understood as implicit race or gender stereotyping.”

Senate Bill 460,, introduced by state Sen. Lana Theis (R-Brighton), explicitly bans “critical race theory” from being taught in schools and threatens to cut 5% of the school’s funding if the state determines that it is violating the law. The Senate Education and Career Readiness Committee, which Theis chairs, approved the bill last October.

“Critical race theory threatens Michigan’s K-12 students with a dangerous false narrative about our country and its place in the world,” said Theis at the time. “It is an extreme political agenda that is manipulating academia and now targets private businesses, public institutions and, sadly, our K-12 classrooms. Our schools should be teaching students our country’s real history, including its faults and flaws, but especially this nation’s founding principles of individual freedom, liberty and equality that so many have given their lives to defend. Critical race theory is an affront to everything our country stands for. Our children should be taught to respect each other equally because of their humanity, not to discriminate based on some identity group or race.”

Sen. Erika Geiss (D-Taylor) called it a “shortsighted, inappropriate and corrupt bill.”

“This bill will have a profoundly chilling effect on education, our ability to foster talent development, and career readiness for today’s Michigan youth, which would ultimately — and negatively — impact the state’s economic future,” said Geiss, who is Afro-Latina, a parent of school-aged children and a former public school educator.

The Michigan State Board of Education passed a resolution in January to push back against the CRT bills.

Addressing cultural diversity

For years, DPSCD’s social studies department published a book guiding students through the structure of Detroit’s government and “community civics.”

The book, and corresponding civics course, was taught in Detroit schools as early as 1938 and the final class occurred in the late 1970’s. The school district’s school enrollment has been majority African American since 1963.

The 1968 manual, for example, wrote about Lewis Cass’ tenure as Michigan governor, but does not point out that he was a slave owner.

The document does point out that “every Detroit public school has been open to children of all races since 1869” but doesn’t mention that Fannie Richards, a Black woman operated a private for Black children prior to 1869 and fought the school district all the way to Michigan Supreme Court to racially integrate the school district. Willam Ferguson was among the first Black students to attend the school district. In 1892, he became the first African American elected to the Michigan House of Representatives.

It also does not point out that the Board of Education was all white until Remus Robinson, a Black physician was elected to the body in 1955. It does not mention that the school district did not have a Black principal until Beulah Cain Brewer in 1947.

The new publication, “Citizen Manual Detroit,” is designed to help its users develop a deeper understanding of the history of Detroit, its government, the government’s roles and responsibilities, and how citizens of the city can work within the government systems to bring about change.

It offers the contributions of organizations such as the African-American-led Trade Union Leadership Council, League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Westside Mothers, as well as Latin Americans for Social and Economic Development (also known as LASED), Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (also known as ACCESS) and others.

“These organizations, and many more, were established by individuals and groups that identified needs within their respective communities and used civic engagement and civic action to address them,” the new manual reads.

The new manual also includes passages that highlight African American broadcast legends Martha Jean “The Queen” Steinberg; William V. Banks, the lead force in launching WGPR-FM 107.5 radio and WGPR-TV 62, the nation’s first Black-owned television station as well as Haley Bell and Wendell Cox, who launched WCHB-AM 1440 radio, the nation’s first Black-owned station founded in 1956 after federal license application.

“The Citizen Manual is a concrete example of [student empowerment and civic engagement],” said Vitti. “By recognizing students’ expertise on their neighborhoods’ needs, inspiring them with the rich history of activism in Detroit, and equipping them with concrete tools to get involved, students see themselves as leaders capable of building a stronger Detroit.”

Michigan Advance is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Michigan Advance maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Susan Demas for questions: info@michiganadvance.com. Follow Michigan Advance on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)