Coronavirus Separates Student Teachers From Their K-12 and College Classrooms, Forcing Them to Scramble and States to Change License Rules

By Laura Fay | April 29, 2020

On a Friday afternoon in early April, a group of student teachers joined a Zoom call hosted by Joy Ross, who coordinates student teacher programming in the Cherry Creek School District outside of Denver. After a body scan meditation exercise, the teachers-in-training entered how they were feeling on a scale from 1 to 5 in the chat section of the app. A few share that they’re worried about their students and family members amid the spreading coronavirus pandemic, which has shut down schools and turned routines upside down.

The Zoom meeting, called “Being Well in the New Normal,” is part of the Growth Squad, an effort by Ross and her colleagues to support student teachers and help them feel connected to the district. The last day of in-person class in Colorado was March 12, but students teachers there are meeting regularly — virtually — with their students and the other teachers from their placement schools. Colorado schools will not reopen before the end of this academic year and might even remain closed into the fall.

Ashley Cosgrove, a student teacher in a seventh-grade English classroom in the district’s Falcon Creek Middle School, said she talks with her cooperating teacher — the full-time teacher who works with her — multiple times a day, helps plan lessons and communicates with their students daily.

Still, not seeing the kids in person has been hard on her.

“Being a student teacher, you’re in a weird spot where you try and build relationships as quickly as you can because you want to connect with the students and kind of dive in, and I think you don’t realize how much these kids will matter,” she said. “They’re really special to you because they’re really your first students, and there’s just no closure to that.”

Around the country, student teachers face a uniquely challenging situation, physically disconnected from both their colleges and the schools where they expected to be student teaching this semester. Many are unable to finish up final tests for teacher licensure and, like most children, teachers and parents, experienced an abrupt transition to remote learning at both institutions. Meanwhile, fewer students have been enrolling in university teacher training programs in recent years, and many school leaders struggle to fill teaching positions every year. With that backdrop, COVID-19 has forced states to make a patchwork of decisions about waiving or postponing licensure requirements, and those adjustments have prompted concerns from some teacher quality advocates.

Cosgrove, who is 30 and will graduate this spring from the Metropolitan State University of Denver, said the only hiccup for her so far has been the cancellation of a standardized test she needs for certification. She’ll have to take it later than expected, possibly getting a provisional license in the meantime that she can convert to a full one when testing centers reopen.

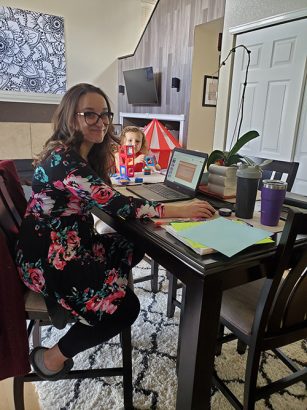

Kayla Townsend, Cosgrove’s cooperating teacher, said investing in student teachers — even as Townsend is adjusting to online teaching herself and overseeing her own child’s education at home — matters.

“We want our kids to have good teachers going forward, and I want to do what I can to help make that happen,” Townsend said. Cherry Creek schools enroll more than 55,000 students who speak 150 languages, and 29 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, according to the district’s website.

On the other side of the country, student teacher Danielle Dover helps her cooperating teacher with virtual learning plans and records video read-alouds for a class she’s never met.

Dover, who is in her fifth year at The College of New Jersey and will graduate with a master’s degree this spring, spent the first part of the spring semester student teaching in Austria as part of an international program for future educators. When she returned in early March, she had to self-quarantine for 14 days. By the time she was able to return to TCNJ and Sunnybrae Elementary, the school in Hamilton, New Jersey, where she was placed in a fifth-grade classroom for student teaching, both were shuttered.

While her mentor teacher has included Dover in planning meetings and in the Google Classroom, it’s been “tricky” to participate without having met the kids in person, she said.

“I feel like I’m still getting something out of it because my cooperating teacher is being very nice and helpful, and she’s trying her best to help me with everything that I need to do, but since it’s not in person, I’m not getting out of it what I could have,” Dover told The 74.

Student teachers as ‘first line of future employees’

In schools across the U.S., student teachers are experiencing various levels of involvement in K-12 classrooms, as educators and administrators adjust to new ways of teaching. Although the semester looks different than they imagined, student teachers who spoke to The 74 said their districts and universities were helping them make it work and said they expect to be ready to teach on their own in the fall, even if where and how they will teach — in a classroom or virtually from home — is still uncertain.

The education system “can’t absorb” a year without any new teachers graduating, said Talia Milgrom-Elcott, president of 100Kin10, a network of organizations that support STEM teacher recruitment and training.

“I think it’s really important even to just assume that candidates may not have had the experiences that they would have traditionally had, and that they need [extra] support” —Eric Duncan, senior data and policy analyst for educator diversity at The Education Trust

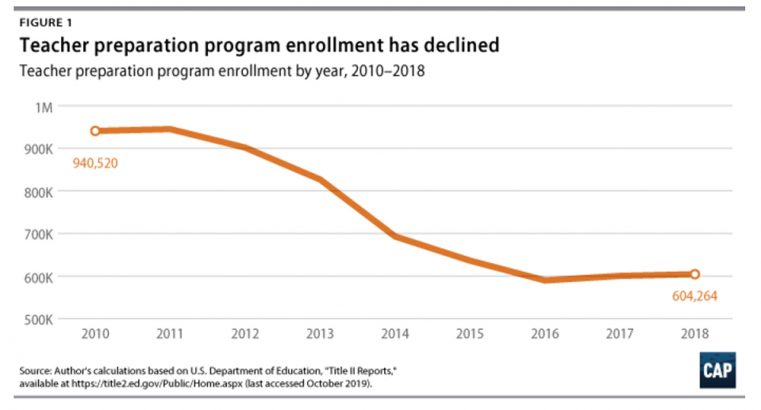

Over the past decade, enrollment in teacher training programs has declined by about a third, according to a report by the Center for American Progress released last year. Additionally, nearly 80 percent of schools reported having empty teacher positions in the 2015-16 academic year, with about a third saying it was “very difficult” to fill vacancies in at least one field, National Center for Education Statistics data show. Teacher shortages vary from region to region, and some subjects, such as science and special education, are more difficult to staff than others.

Students from already vulnerable groups, such as those from low-income families and students of color, are more likely than others to have teachers who are less qualified or less experienced, and disrupted teacher training could exacerbate that, said Eric Duncan, senior data and policy analyst for educator diversity at The Education Trust, an advocacy organization.

“I think it’s really important even to just assume that candidates may not have had the experiences that they would have traditionally had, and that they need support” and extra mentoring when school resumes, Duncan said.

In Cherry Creek School District, the Growth Squad leaders are also talking to student teachers about practical things they might not get to observe this semester, such as how to open and close out a school year, and offering them mock job interviews. Cherry Creek Schools was unusually supportive of student teachers even before the pandemic hit, said Ross, a human resources director who oversees recruitment, retention and partnerships with universities. She said that’s in part because the district wants to invest in future teachers — and then hire some of them.

“We have been intentional in designing a very comprehensive approach, looking at student teachers as an opportunity for us to invest in them, looking at them as, truthfully, our first line of future employees,” Ross said.

The programming for student teachers is part of a wider “grow your own” effort to recruit and train teachers for the district, said Brenda Smith, Cherry Creek’s chief human resource officer. In recent years, there’s been a “pretty dramatic dropoff” in the number of people entering the education profession, Smith said, and making sure new teachers and student teachers have access to quality professional development is one way to help good teachers grow and stay in the district.

Cosgrove, the student teacher, said the extra support from the district — which has adapted to meet issues arising from the pandemic and also has responded to what student teachers want to learn — might be a benefit to come out of the coronavirus.

“It doesn’t replace what we can’t learn in person,” she said, “but I can’t help but think that there’s going to be so much insight from this that we would have never had the opportunity to get had we not been in this situation.”

At least 43 states “have ordered or recommended school building closures for the rest of the academic year,” Education Week reports. But some leaders are starting to warn that it might not be safe to reopen in August or September either.

In an April 21 call with district superintendents, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis said to “prepare for the possibility” that traditional in-person classes will not resume until January 2021, The Colorado Springs Gazette reported. Polis also said districts should develop some other unusual plans for reopening, perhaps with staggered start times and other social distancing measures in place.

Sandra O’Dowd, a student teacher at Antelope Ridge Elementary in the Cherry Creek School District, said learning to teach online could also prepare student teachers in case schools remain virtual for part of next year, though she hopes that’s not the reality.

“I want to get back to the classroom, but if that ends up happening, the skill set to be an online teacher is not really stuff that we planned for in university — because who saw this coming?” she said. “So in that way, for sure, if we need to learn how to do this for a little while, definitely it would help me in August” if classes are still happening remotely.

Finding a ‘pathway into the classroom’

State governments oversee teacher licensure, and the requirements vary from state to state.

For instance, in New Jersey, would-be teachers are required to submit and receive a passing score on the edTPA, an intense portfolio assessment administered by the testing company Pearson that requires in-depth lesson plans, videos from the classroom and a student assessment. This year, the state has said teachers can graduate with a provisional certification and complete the portfolio next year when they are working full time as teachers. Tabitha Dell’Angelo, a professor of urban education at TCNJ who oversees student teachers, wants the state to waive the edTPA altogether for this year.

Dover, the student teacher from New Jersey, said she’s not going to complete her edTPA this year because she won’t be able to record herself teaching. She’s already had some interviews about jobs for next year, and she said school leaders so far have been understanding that she’ll have to complete the portfolio during her first year of teaching.

The student teachers “have such good attitudes about it, but they’re definitely feeling discouraged, I think, that they’ve done everything they could and then at the end of this they still might not get what they worked for,” meaning a full teaching license upon graduation, Dell’Angelo said.

But state officials should balance the need for new teachers with a strong vetting process, said Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, an advocacy group that pushes for higher teacher preparation standards. Lacking the regular measures used to evaluate teachers also “puts a greater burden on districts to make sure that the folks they’re hiring are going to be competent,” such as by collecting writing samples or asking candidates to grade student work and interpret standardized test results, she said.

“You’re going to have to find a pathway into the classroom for these folks, that holds them harmless, but on the other hand, you don’t want kids to be the victims … of the ceiling falling in, and the kids will be the ones who pay for it,” Walsh told The 74 in an interview. “So I think that this puts a greater burden on districts to make sure that the folks they’re hiring are going to be competent.”

States are taking two approaches to teacher licensure this year, according to an analysis by the National Council on Teacher Quality. Some states including California, Georgia, Kentucky, New Jersey and New York, are allowing online teaching to count toward student teaching requirements. Others, including Alabama, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, South Carolina, Texas and Vermont, are waiving or reducing the minimum amount of time required for student teaching and assessing candidates based on the teaching they’ve already done. To give student teachers more flexibility, California is allowing student teachers to work with any “experienced educator” and get feedback, even if that person is not the originally assigned cooperating teacher.

The Colorado Department of Education is telling students it will work with them through the licensure process and “will hold your application open for a reasonable amount of time so you may complete the license requirements.”

As far as other licensing requirements such as standardized tests go, states are taking similar approaches. Some are waiving tests and allowing teachers to get a full certification at the end of the academic year. Others have said they will grant candidates provisional certifications that will allow them to start teaching in the fall and complete tests and other requirements within a certain amount of time.

Walsh said her recommendation would be for states to grant emergency licenses that allow teacher candidates to start teaching full time in the fall and give them a year to complete any remaining requirements and receive their full license.

“This whole situation has really pushed to make you realize how much you care about the kids. That sounds dumb because you go into teaching because you care about kids, but if anything … it’s been a huge affirmation that this is where I need to be.” —Ashley Cosgrove, student teacher

While maintaining high expectations for teachers, states also need to make sure application fees and other costs aren’t excluding teachers of color from entering the profession, said Tanji Reed Marshall, director of p-12 practice at The Education Trust. That might mean delaying the cost until people start teaching, waiving fees or making them proportional to a candidate’s current income, she said. Nonwhite teachers benefit students of color and are underrepresented in the field, research shows.

“We need states to be thinking about barrier removal as opposed to removal of requirement,” she said. “We want the rigor, we want the demand, we want the excellence … and we want any barrier to be removed for those access points that would do anything to further diminish a diverse teaching force for kids.”

To receive certification, Colorado requires teachers to submit a performance portfolio that includes lesson plans and student assessment data. Cosgrove had planned and taught her lessons before school shut down, and she sent the assessment to her students online, but she had to make it optional for the 28 students in her class; 22 completed it. Though the results aren’t perfectly valid, it was enough for her to submit to the state.

Despite the disorder and added stress of this pandemic semester, Cosgrove said the experience has cemented her dream to be an educator.

“This whole situation has really pushed to make you realize how much you care about the kids,” she told The 74. “That sounds dumb because you go into teaching because you care about kids, but if anything … it’s been a huge affirmation that this is where I need to be. This is where my heart work is at.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to the National Council on Teacher Quality and The 74. The Carnegie Corporation of New York and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provide financial support to 100Kin10 and The 74. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bloomberg Philanthropies, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Foundation and Walton Family Foundation provide financial support to The Education Trust and The 74.

Lead image: Cherry Creek School District student teachers and staff during a virtual meeting. (Joy Ross)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter