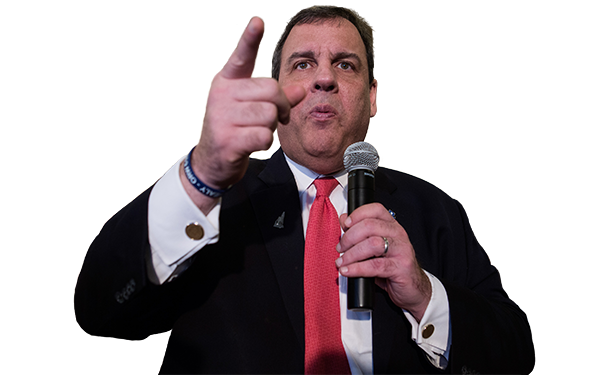

Christie Plan for Funding NJ Schools Widely Criticized; Cami Anderson Warns of ‘Devastating Impact’

“Spending does not equal achievement — never has and it never will,” said Christie, the presidential candidate turned Donald Trump booster. Instead of distributing state aid progressively based on a variety of factors, the governor’s plan would fund every student in the state at the same rate, $6,599 per pupil (except for those with special needs).1

But in interviews with The 74, experts on school funding, advocates of charter schools, and the former superintendent of Newark schools say the proposal if enacted, will likely harm low-income students.

Christie asserts that dramatic funding cuts won’t hurt kids in urban schools. But Cami Anderson, the controversial Christie-appointed, former chief of Newark Public Schools said otherwise.

“Any proposal that cuts in half what urban districts spend will clearly have a devastating impact on students especially in the absence of other reforms. Students in poor communities deserve big investments in things like more time in school, top-notch technology, books, and services for english language learners, to level the educational playing field and help end inter-generational poverty,” she told The 74.

Eric Hanushek — a Stanford professor and influential proponent of the idea that spending more doesn’t necessarily translate into better outcomes — said in an email, “Even if the large increases in funds have not led to much in the way of achievement gains, it is not clear that dramatic cuts will not hurt.”

Hanushek agrees with Christie that schools are inefficient, but argues that employment contracts prioritizing seniority in layoffs and other personnel decisions limit the ability of districts and schools to reduce spending. In other words, the very inefficiencies that Christie says plague the system would make funding cuts all the more harmful.

Nor is it even clear how inefficient the current system is. A significant body of recent research suggests that simply giving districts more money does improve student outcomes, contra Christie’s charge that resources and achievement are completely disconnected.

The governor noted that many districts receiving large sums of state aid have low graduation rates; he doesn’t mention that they serve a much more disadvantaged population than the state as a whole. Performance may grow even worse in the absence of significant resources. A recent analysis found that, accounting for demographics, New Jersey students scored second best in the country among all fifty states on national tests.

“If this policy will lead to large permanent reductions in per-pupil spending in those urban districts serving low-income students, it will very likely have deleterious effects on the short- and long-run outcomes of these students,” said Kirabo Jackson, a Northwestern University economist and coauthor of a widely-cited study showing that school funding increases have long-term benefits for students.

Christie praised the state’s charter sector, but while charter schools in Newark seem to outperform the city’s traditional public schools, that’s not the case, on average, in other cities in the state.

Meanwhile, some charter advocates are unhappy with the proposal. Nina Rees, president of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, criticized Christie’s plan in an interview. “We need to look at rewarding high-performing schools with additional funds rather than simply an across-the-board cut that stands to harm high-achieving public and charter schools,” she said. Charter may be hit particularly hard because they are disproportionately based in urban areas.

The New Jersey Charter Schools Association reacted tepidly to the plan.

Anderson argued that strong charters could be hurt by steep spending reductions.

“It is important to remember that there are good charter schools and terrible charters schools and that growing the charter sector rapidly can have a devastating impact on students in a shrinking district in the absence of a city-wide plan,” she said. “The high-performing charters who are committed to equity (not all are) serve a similar student population to district schools and get way better results for about the same amount of money (if you include all of what they spend including philanthropic dollars and facilities money) — which is why I enthusiastically supported their growth in Newark. They could not survive if their all-in per pupil was cut in half.”

Christie said that “we will insist that this new funding formula reward our successful charter schools with funding that comports with their success,” but he has not explained how a separate funding stream would work.

A spokesperson for Christie said in an email, “No one in New Jersey has a more supportive record on charter schools, and he acknowledged that there needs to be changes in the charter law to be certain the charter schools are not adversely impacted by the change in the state funding formula for public schools.”

Even some conservatives say the new plan, an effort by Christie to lower property taxes, goes too far. Mike Petrilli, of the right-of-center Fordham Institute, told The 74 in an email, "Governor Christie may be right that property taxes are out of control, as is government spending in some municipalities. But taking it out on kids from poor families is like punishing a gambling addict by taking away his kids' lunch money.”

Christie’s argument that every student should get the exact same state resources may seem like common sense, but in fact it would strongly favor students from wealthier, mostly white communities. More affluent areas are better able to raise money for schools because their high income and property values creates a much larger local tax base. Equal state funding on top of unequal local funding leads to inequity overall.

“Virtually every state in the union recognizes that state funding must compensate for low property tax bases when local property taxes are a significant proportion of total funding,” said Hanushek. “Particularly given the large number and highly variable districts in [New Jersey], not recognizing differences in tax bases would introduce some very destabilizing impacts across districts.”

Moreover, disadvantaged students — for example, those in poverty and those learning English as a second language — cost more to educate.

Dan Weisberg, president of the reform group TNTP wrote in a blog post, “Newark serves far more students who are English learners, have learning disabilities, and are dealing with housing instability and the traumatic effects of poverty. Those children are morally (and legally) entitled to more services that will give them an opportunity to succeed.”

Jackson echoed this point. “It is well-documented that it is more difficult to attract and retain high-quality teachers in low-income urban school districts than in more affluent areas. As such, it costs more money to provide the same quality of instruction in these difficult to staff schools. This point highlights the fact that equal spending across districts does not mean equal instructional quality.”

1. Some argue that Christie’s plan would lead to an even lower per-pupil rate due to the cost of long-running programs that the governor is unlikely to cut. According to one estimate, the rate might actually be around $4,800 state-wide. (return to story)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)