Chris Stewart: It’s Been 65 Years. Maybe It’s Time to Stop Expecting the Promise of Brown v. Board to Be Fulfilled

This essay is part of a special series commemorating the 65th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case. Read more essays, view testimonials from the families who changed America’s schools and download the new book Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision at our new site: The74Million.org/Brown65.

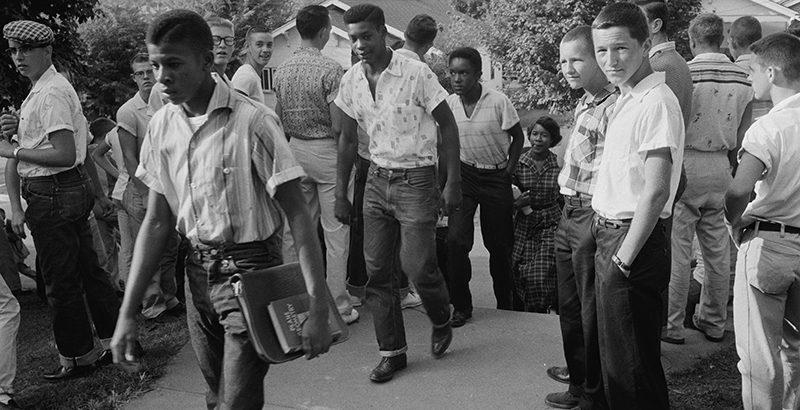

Every few years, there is a predictable tide of articles proclaiming that it’s the anniversary of Brown v. Board and our schools are still just as segregated as they were when the landmark decision was handed down in 1954.

What you won’t find in any of these articles is much sober reckoning with the fact that integration was a colossal failure that in many instances produced more damage than progress. Instead, they will tell us once again — as many integration fundamentalists will always do — that we must once again fight for white-flight-proof school boundaries, a rejoinder that sounds like recalling weary soldiers back to a lost war.

I believe black folks should resist integration proposals as the sole or primary educational interventions necessary for our children to succeed. We lost so much by placing our faith in the social engineering of schools that robbed us of black educational capital and infrastructure. Our teachers fired. Our principals demoted. Our children handed over wholesale to an education establishment that had no reason to love them.

In the process, we learned that a quality education can be had without integrated schools.

If you ask the most visible public school integration advocates why we have “resegregated” schools so many years after massive and expensive attempts to fulfill the promise of Brown, they mostly likely will say some version of “desegregation was working but we lost our will to see it through.” They are dangerously wrong and insufficiently prepared for any room where serious debates about education occur.

I assume most of us start out as fair-natured integrationists. None of us want the curse of backward bigotry on our souls. Maybe because of this fear of being labeled racist, we avoid rational skepticism even when proposed remedies for segregation may actually cause more of it, as wide-scale busing did in the 1970s.

It may comfort us to know there is a long line of individuals — some humble, some famous — who made the move from naive integrationist to experienced realist with their reputations peerless and bigotry-free.

When public school integration efforts hit high gear in the late 1960s, Virginia Williams considered herself “very much an integrationist.” A decade later, when the Washington Post caught up with the black educator at Fort Hunt High School in Fairfax County, Virginia, she wasn’t as positive.

“I have been thinking that from several standpoints, black students were better off in a segregation system,” she told a reporter.

Williams’s journey is a common transition people make from aspiration to reality, from the idea that we must strive to achieve a beloved community in public schools to the post-desegregation weariness that sets in after efforts to strong-arm parents into racially balanced schools fail spectacularly.

Dr. Kenneth Clark, famous for sociological research used to demonstrate the effects of segregation on black psychology, made a journey similar to Williams’s. Twenty-three years after his work was used in the Brown decision, he had developed a different critique of public schools. As schools integrated, he wrote, black students weren’t “held to standards,” and “they’re told they don’t need to know how to read — that any language they speak is acceptable.”

Clark complained that incompetent teachers and their unions were lording over schools that were “brainwashing [students] into a sense of inferiority.” His remedy was no longer integration. “What we need are teachers in the elementary grades who are competent to teach reading, spelling, arithmetic and writing,” he said.

James Coleman, whose 1966 report Equality of Educational Opportunity studied 600,000 students and 60,000 teachers in 4,000 schools, drew the myth-shattering conclusion that the racial composition of classrooms was a stronger driver of black student performance than school resources or classroom instruction. That finding was the basis for widespread desegregation of public schools as a social priority, and as a primary educational intervention.

Yet, by 1978, Coleman had reconsidered. Noting the review of more than 100 studies on the results of desegregation efforts, he said there were “no overall gains” and “…either no achievement effects or else losses.”

Coleman, a civil rights advocate who knew what it meant to be arrested for protesting unjust barriers to equity, then made another unlikely turn: He became a vocal supporter of publicly funded scholarships that opened doors to private and parochial schools for low-income black families.

White flight emptied cities of families who took their social capital and tax bases with them. In just seven years, Prince George’s County in Maryland went from 127,296 white students in 1970 to 78,476. Cities from Detroit to Los Angeles watched segregation intensify as forced busing (the most common instrument used to achieve racial balance in schools) stoked public outrage and fear.

Before Brown, public schools for black children were woefully under-resourced, but often rich with strong black teachers who at times were better credentialed than white ones. After desegregation, black students are trapped in poorly appointed schools, but now with an additional — and even more critical — deficiency in that they are without the institutional knowledge gained in the years when black children were taught by black teachers.

Of all the pernicious results of Brown, the gross characterization of black schools as inherently inferior purely by their blackness was the most irredeemable. Coleman said the idea that all-black schools are inherently bad “has a curiously racist flavor which I can’t accept. There have been, and there are, all-black schools that are excellent schools by any standard.”

W.E.B. Du Bois had made that observation as far back as 1935, saying the “mixed” public schools of Harlem, in New York, didn’t offer an education that is “in any sense comparable in efficiency, discipline and human development with that which Negroes are getting in the separate schools of Washington, D.C.”

Du Bois argued that black schools could be just as strong as white schools, but he mourned that “as long as American Negroes believe that their race is constitutionally and permanently inferior to white people, they necessarily disbelieve in every possible Negro institution.”

Perhaps it’s time we believe in ourselves and reclaim responsibility for educating our children. One leap into that direction begins by admitting that Brown is not the big idea for ending the gap between black student underperformance and black educational excellence; it’s not the key to breaking the cycle of poverty for many black families; it’s not the key to making white people less racist, and it’s not a school reform that will restore the teaching and learning that existed before the illusion of integration wiped away our assets.

We have learned through education reform that it is possible to build schools with black children’s needs in mind, schools that help them reach their potential. Some of these schools are charters, some are magnets, and some are traditional district schools that reject the idea that the brilliance of black children can be ignited only by the torch of white peers.

Yes, it’s been 65 years since the Brown decision promised integrated schools and better education. That’s too long for us to have ignored that the goal is quality schools however they may be composed.

Chris Stewart is the CEO of Education Post, a media project of the Results in Education Foundation. Prior to leading Education Post, he served as CEO of the Wayfinder Foundation. He is a lifelong activist and 20-year supporter of nonprofit and education-related causes. In the past, Stewart has served as the director of outreach and external affairs for Education Post, the executive director of the African American Leadership Forum (AALF), and an elected member of the Minneapolis Public Schools Board of Education, where he was radicalized by witnessing the many systemic inequities that hold children back.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)