Child Welfare Calls From Oregon Schools Dropped 30% During Distance Learning

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

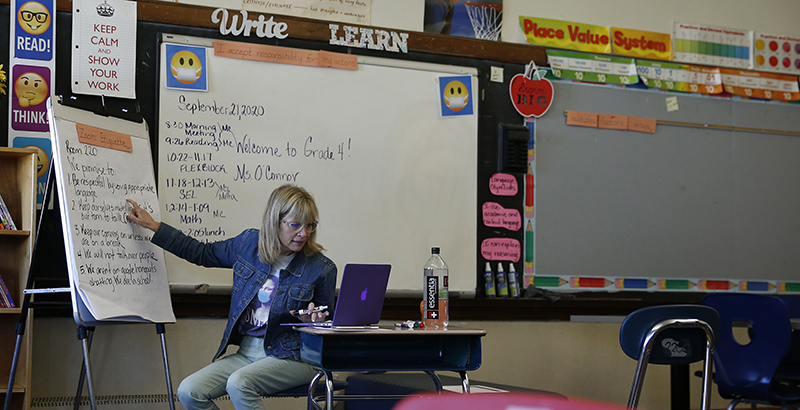

Superintendent Tom Rogozinski, superintendent, was taking stock of the months his students spent under distance learning, and noticed a steep decline in calls from staff to the state Department of Human Services over concerns about student welfare.

From the fall 2019 to spring 2020, before the coronavirus forced schools to move online, the district’s mandatory reporters – everyone from teachers to bus drivers – had called the state agency 84 times to report their concerns.

While schools were operating with distance learning the following fall, just 11 calls were made.

Rogozinski felt the decline in calls wasn’t because kids suddenly weren’t struggling with the same issues they were before the pandemic, but that their teachers were mostly blind to them.

“We learned that unless we’re physically interacting with a lot of these kids, we just don’t know,” he said about students’ home lives. “It speaks to those relationships that educators form with kids,” Rogozinski said. Outside of schools, “these students, when they have situations and they don’t know where to turn, there’s not a lot of places for them to turn to.”

Schools in counties across the state reported lower calls to the Human Services Department and the Oregon Child Abuse Hotline during distance learning. In 2019, more than 20,000 reports came in from schools. In 2020, there were 14,076.

Abuse and neglect aren’t always at the center of a caller’s concern. It’s inadequate food or housing.

Jake Sunderland, press secretary at the department’s child welfare division, said that’s about half the calls that come in.

“They’re actually people calling because they know a family needs some extra support but they don’t know where to turn,” he said.

Warrenton-Hammond is routinely on the state Department of Education’s list of Oregon districts with the highest percentage of homeless students. Rogozinski said anywhere between 15 and 20 percent of the students in his district each year fit the federal definition of homelessness.

“We have a very unstable, very transient population,” Rogozinski said. “When we talk about competing values around the return to schools and safety we also need to talk about this.”

Sunderland said that despite the drop in calls to the Human Services Department, there was not a proportional drop in the number of calls that ended up resulting in an assessment for neglect or child abuse. Each year, only about a quarter of all the calls that come into the state end up warranting a full assessment and investigation, and that was the case during the school year under distance learning as well.

“I do want to dispel the myth that kids were almost inherently unsafe at home because they didn’t have the watchful eyes of other teachers on them,” he said. “The truth regarding that statement is – we do not know yet how the pandemic affected actual rates of abuse and neglect,”

It’s further complicated by a change made in 2019 to streamline calls to the department over child welfare. The Department of Human Services went from 18 regional phone numbers to a single, statewide hotline.

“We don’t really know what a typical number of calls of abuse and neglect should look like in Oregon right now,” Sunderland said. “When you make one hotline, you increase awareness and make it easier to report, so you can expect calls to be higher. We’re kind of in this area where we don’t know what normal would be,” he said.

What has remained consistent over the years is the disproportionate number of calls that come through about students and families of color.

“We know structural and systemic racism play a role when it comes to reporting suspected abuse and neglect,” Sunderland said.

For that reason, the department has been working on revamping training for mandatory reporters so they can recognize biases, and to consider other options for connecting kids with resources instead of calling the hotline. .

Sue Rieke-Smith, superintendent in Tigard-Tualatin, has created a “basic needs team” to connect students and families with resources so the state isn’t getting called.

“It’s culturally driven,” she said.

The team works with community organizations like the Immigrant & Refugee Community Organization, the youth empowerment group REAP and the non-profit Latino Network to help get students and families the resources they need.

“We’ve been able to get at food insecurity, health care, vaccines. Even with all that, we know there was a great deal of underreporting,” Rieke-Smith said about the period students undertook distance learning.

Sunderland said that when people call the Child Abuse Hotline and the issues are around food and housing, the Human Services Department ultimately ends up referring people to resources that a mandatory reporter could have done directly.

“When you see a family in need, in crisis, that’s struggling but you don’t think there’s abuse and neglect, the best thing you could do is to help them get plugged into resources. That being said, when you do suspect it, definitely call,” he said.

Trying to help a family dealing with housing or food insecurity? Consider accessing the following resources:

- Dial 2-1-1, or text your zip code to 898-211 to get connected to local food, housing, child care and other supports in your community.

- Find a food local pantry by visiting foodfinder.oregonfoodbank.org.

- Learn about government programs and community resources for older adults and people with disabilities by contacting the Aging and Disability Resource Connection of Oregon at 1-855-673-2372 or www.adrcoforegon.org.

- Apply for government food, cash, child care assistance and the Oregon Health Plan online at ONE.Oregon.gov or by calling 1-800-699-9075.

Of course, when an educator or other caring adult suspects a child is experiencing abuse or neglect that person should, and may be required by law, to report that concern to the Oregon Child Abuse Hotline by calling 1-855-503-SAFE (7233).

This article originally appeared in Oregon Capital Chronicle

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)