Newark, N.J.

It’s the start of a September school day and Chris Cerf is busy roaming the halls of Mount Vernon School in Newark’s West Ward. He’s welcomed by a handful of elementary school students who perform a practiced dance in colorful garments representing the diverse countries — from Russia to Nigeria — where they are from.

He pops into a pre-K class where a teacher is quizzing students on the differences between words that begin with the letter M and the letter S.

Then he gets to a room, where a handful of parents are learning about the contentious Common Core standards and PARCC, the state’s new computerized standardized test. He applauds them for getting involved in their child’s education and offers some advice.

“The top thing on my list is making sure your children read every day,” he tells them. “The more that happens, the more they blossom.” Cerf turns to his left and asks for input from Newark Mayor Ras Baraka’s chief education officer Lauren Wells, who further extols the value of reading.

That the two education leaders are together, touring this school — or any school in Newark for that matter — is something of a turning point. While the visit is one of dozens Cerf made to schools during his first weeks as Newark’s new superintendent, he and Baraka have represented two warring factions who have fought bitterly over the direction of the school system and who will get to guide it.

The conflict took on a new tenor this year when New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie named Cerf to replace his former state-appointed superintendent Cami Anderson, who resigned in June after ugly, unrelenting confrontations with City Hall and some community members over efforts to reform Newark’s long-struggling public schools.

The governor also agreed to ramp up the process of returning control of the 35,000-student school district to the city’s elected school officials, who have not had power over the local schools in two decades and have clamored mightily to get it back

Cerf is far from a fresh face, however. He was Christie’s state education commissioner and Anderson’s boss during the controversial era of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million gift to Newark schools recently depicted in veteran reporter Dale Russakoff’s book “The Prize.”

Now, Cerf, a 60-year-old Montclair resident who worked as an associate counsel under President Bill Clinton in his early policy days, is tasked with not only shepherding the district’s return to local control but also making sure the sometimes-hated reforms begun by Anderson don’t die on the vine.

With some of the political divisiveness cooled and relationship-building skills that set him apart from Anderson, Cerf just might be able to bring education reform in for a smoother landing and sidestep some of the political turbulence that has marked the last four years.

The mayor is willing to concede changes in style if not substance.

“I didn’t really have a relationship with Cami. The only difference I really see is that right now at least he’s willing to deal with critics. We disagree on almost everything. When we talk, we disagree,” Baraka said in a recent interview. “The only difference is he’s willing to sit there while I disagree with him.”

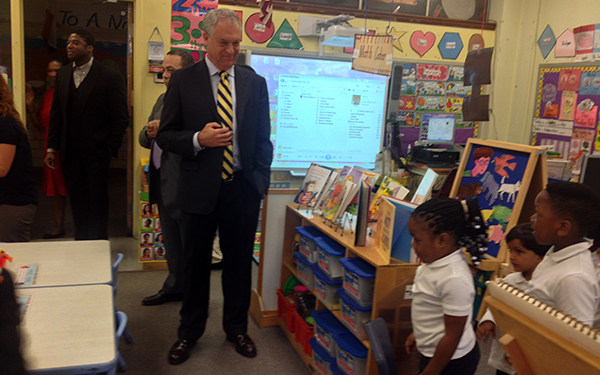

Chris Cerf tours a classroom at Mount Vernon School. (Photo by Naomi Nix)

Animated and intense, Cerf smiles big, waving his hands as he talks with conviction about school equity and expanding opportunities for kids. He grew up in Washington, D.C., and Boston, graduating from Amherst College in Massachusetts and Columbia University Law School in New York City. After law school and before the White House, he clerked for former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

In 2004, Cerf took on his first major role in public education when he served as deputy under New York City schools Chancellor Joel Klein. During that time, Klein’s team launched its own multi-pronged reform attack on a urban district whose 1.1 million students dwarf the rest of America’s public school systems.

Cerf left that role in 2009 and transitioned into the private sector, where he became the CEO of Sangari Education, a math and science technology company. The next year, Christie tapped Cerf, a Democrat, to be the state’s education commissioner. Under his leadership, the state legislature reformed teacher tenure to make it easier for school districts to fire teachers who are rated ineffective for two years in a row. The education department also oversaw the expansion of charter schools and other reforms in Newark and Camden.

Pushing through political battles on both sides of the Hudson River has given him a new perspective on dealing with critics, Cerf said.

“There is a wonderful saying that is often said about marriage. That you can either be right or in a relationship and I’ve been married 35 years,” Cerf said.

“I think in my younger days, I had such conviction about what was right for kids that I was a little bit (blinded) to the need and appropriateness of bringing people along with you, of hearing people tell you where you are actually wrong despite your convictions,” he said.

“I think I have a greater appreciation now than I did 20 years ago for the incredible urgency of engaging people, even people who sort of disagree.” he added. “I don’t think you compromise your principles, but you need to be open to the fact that your principles sometimes need more careful thinking.”

Many of the ideas Cerf has about education have already been implemented into the fabric of Newark’s school system. During Anderson’s four-year tenure, the school system negotiated a teachers contract that awarded merit-based bonuses to teachers and allowed many schools to expand their school day. The school district also created an open enrollment system, permitting parents to enter a lottery to attend their preferred district or charter school anywhere in the city. Some failing schools were closed as families in the city flocked to better options. (Check out The Seventy Four’s exclusive Q&A with Cami Anderson about her time in Newark)

The district also created a turnaround strategy for schools with low-performing test scores by replacing the principals and staff. Data would later show the program produced mixed results.

As she sought reform, Anderson faced intense political opposition from the city’s teachers union but also from local elected officials, community nonprofits, a slew of Newark clergy members and an outspoken student group. Newark Public Schools Advisory Board meetings became more unruly and aggressive; protests became a constant and garnered a stream of negative media attention.

Even state Sen. Teresa Ruiz, one of the lawmakers who led the charge for teacher reform, became an outspoken critic. While Christie told those outside the city that he was the “decider” of the state-run school district, Anderson took the brunt of the criticism from those living in Newark.

“My sense is that his biggest advantage is that he’s not her,” said Montclair State University political science professor Brigid Harrison. “There was just really a personal dislike for her…I don’t think that you are hearing the same kind of vitriol (about Cerf). That’s not to say he is well loved but I think the personality issue has dissipated since Anderson departed.”

In public appearances, Cerf works a room like someone used to retail politics, Newark-style. He shakes residents’ hands and takes time to chat. He thanks everyone from the security guard to the teacher’s aide for their hard work. He remembers to publicly acknowledge politicians, civic and union leaders in their presence.

Beyond deftness, the governor and the mayor’s joint announcement that the city may get control of the school system after 20 years gave critics who would otherwise be blaming Cerf for a lack of improvement in that area their own prize on which to focus.

Since taking the top schools job, Cerf has been meeting with various nonprofit organizations, involved activists and elected officials. He has pledged to help the city start a community school, a model embraced by New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, in which local philanthropic organizations partner with schools to offer students social services beyond what a traditional school might typically provide.

“I think he sees the sense in it. I also think he knows he’s not going to be here for a very long time. This is a transitional position for him,” said Baraka, who has advocated for the community school approach.

“We are trying to establish something in the long term. If it makes sense, I don’t see why he’s not going to be involved.”

The political dynamic has shifted, for now. During his first appearance before the Newark Public Schools Advisory Board in August, Cerf offered a lengthy presentation defending One Newark, the term Anderson used to label the district’s reform strategy that became anathema to community opponents.

He told them that when given the chance, only a quarter of families with incoming kindergarteners named their neighborhood school as their first choice. Close to half of parents picked a charter school as their first choice. Those numbers, he said, mean One Newark was delivering more educational options to families hungry for choice. (Read how high-performing charters brought real education gains to Newark students)

In the end, the board approved a resolution calling for an end to the enrollment process. The vote packed little punch because Cerf, as a state-appointed superintendent, has full veto power over the board. Critics on the board contend that kids have been forced to go across town to get to school because of the universal enrollment plan. Furthermore, the expansion of charter schools under the district’s reform strategy, they maintain, hurts the traditional public school system.

Wells, the mayor’s chief education officer, recently recently wrote an editorial for the online news site NewarkInc calling for a moratorium on charter schools to allow the public school system time to rebuild. On Monday, Baraka reportedly called a proposal to expand charter schools “irresponsible” because it hurts neighborhood schools.

How can you say you want all children to be successful when you knowingly will expand at the demise of some of them without even a pause!

— rasjbaraka (@rasjbaraka) October 18, 2015

Cerf doesn’t think there should be a moratorium on charter schools but believes that traditional public schools will continue to educate the lion’s share of city students.

The meeting was a defeat for Cerf but he is trying to take the longer view while knowing the clock is ticking. Christie’s term ends in 2017 and it’s not likely he will stay on beyond that.

“I am really optimistic and confident, but I also have bad days. Sometimes the voices of unreason dominate,” Cerf said. “It’s a tough gig. It’s a very tough gig.”

But anyone who has watched Newark politics closely knows the school board meeting could have been much more combative. Cerf did not prevail but he wasn’t eviscerated, either.

In February 2014, Anderson announced she would no longer attend public board meetings because they were not productive. The month prior, she and her staff walked out of a public meeting where hundreds of Newarkers protested a plan for school closures and teacher layoffs. Anderson did not attend another public meeting. Once Baraka was elected, relations between City Hall and the school district got so bad the two entities could not even coordinate a unified response to a suspected meningitis outbreak.

Last month, on the first day of school, Cerf held a press conference at the Barringer Academies, two high schools that made headlines last year because so many students started with mixed-up schedules and substitute teachers. Newark City Council President Mildred Crump stood next to him, as he announced that the district was prepared to serve students at Barringer and all city schools.

“The last superintendent disengaged with the community and refused to attend meetings,” Crump, a vocal critic of Anderson, said afterwards.

In addition to meeting with Newark constituents, Cerf must deal with a range of practical issues. The district had a $60 million budget deficit earlier this year which has been whittled down to $15 million. How it will eliminate the remaining shortfall is unclear. The contract with the union representing the district’s 64 principals has also expired.

Cerf faces an uphill battle if he wants to go beyond a political honeymoon and truly win the hearts and minds of Newark residents. He runs up against a perception that he is part of an administration that steamrolls the community’s wishes in top-down style to accomplish a reform strategy. He remains a white outsider with ties to some of the wealthy private industry interests that anti-reformers disdain.

Newark Public Schools Advisory board member Antoinette Baskerville-Richardson said she has her doubts that Cerf will be able provide the transparency and policy course correction necessary to rebuild the community’s trust. “Smiling” at public appearances will not be enough, she said.

“It’s quiet now,” she said. “Sometimes the quiet is the quiet before the storm.”

In Russakoff’s “The Prize,” Cerf appears to give the impression at times that bypassing local politics was a necessary evil to getting reform done.

“I wish I had fully appreciated the need for deeper and greater engagement,” he acknowledges while also arguing that Russakoff’s telling did not fully hold accountable the powerful forces that aligned to protect a failed bureaucracy.

“I wish that the people who rolled this out had laid the groundwork in the community more deeply than announcing (the $100 million) on Oprah.”

Being there on the ground, in the schools, listening was evident in Cerf’s recent tour of Mount Vernon School. He asked the school’s principal, Bertha Dyer, how the central office could better support her efforts. They talked about the possibility of English language classes for parents and installing a science lab.

Cerf then applauded her for the school’s academic success — a bright spot whose students perform better on state tests than their peers in other New Jersey districts.

The question is “How do we make it go viral,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)