Brown v. Board at 65: Sherrilyn A. Ifill on Why We All Need to Know More About the Brave Black Students Who Integrated Schools in the 1950s

This is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

A generation of young people were inspired to become civil rights lawyers by images of brilliant and crusading civil rights lawyers like Thurgood Marshall, Constance Baker Motley and Robert Carter who, in their own right, transformed the course of our nation in the 20th century. These lawyers accomplished the goal that Marshall described as “breaking the back of Jim Crow” — that deeply entrenched and violently-maintained system of racial segregation that was the law of the land throughout the south.

But it is only once you become a civil rights lawyer that you learn that it is your clients — the men, women and even children who risk it all to challenge injustice — who are the real heroes of our civil rights legal stories. I learned this early on during my first tour of duty as a Legal Defense Fund (LDF) lawyer beginning in the late 1980s. Even then, meetings about our litigation in the rural south were often held in churches and funeral parlors — locations in which African Americans could feel a measure of security from the scrutiny of whites who might retaliate against African Americans who were seen meeting with civil rights lawyers. Our clients and their families overwhelmed me with their quiet courage and dignity, with their warmth and with their sense of humor in the face of crushing inequality.

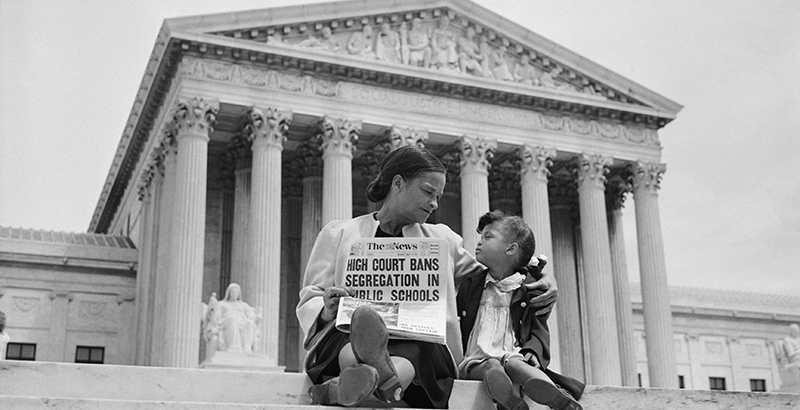

No clients were more courageous and inspiring than those families who formed the sprawling group of plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education. Across four states and the District of Columbia, these African American families stepped out of their ordinary lives into the glare of history. For some, the consequences were devastating. Harry Briggs and his wife Eliza suffered severe reprisals as a result of their participation in the South Carolina Brown case, Briggs v. Elliott. After losing their jobs, they moved to New York, never to return to live in South Carolina. For others, the glare of the spotlight, the iconic photos that froze the “Brown children” in a sepia tableau, was its own pressure and challenge.

It is also critical to remember that the plaintiffs in these cases were not just swept up by history. They created history. It was 16-year-old Barbara Johns, who courageously led a school walkout of her fellow students in protest of the inferior resources provided at her segregated high school, that pushed LDF to file the first Brown case, Davis v. Prince Edward County, Va.

The lonely walk of so many of the children as they took those first steps into the hostile territory of newly integrated white schools has never been adequately explored. These children are veterans of America’s 20th century domestic war — the Civil Rights Movement. That war claimed victims across the south — some were literally killed in its battles. But the children who first integrated southern schools were our soldiers. They braved the front every day, engaged in skirmishes, returned to the front day after day, with their wounded spirits freshly bandaged by the love and support of their families and communities. They should be embraced today as heroes. Their sacrifice and that of their families transformed the meaning of equality and democracy in our nation. They reshaped American identity.

What is most important today is that we take the time to read the accounts of these plaintiffs, the clients, those whose stories are hidden by the dismissive Latin expression “et al.” in the case captions. It is past time that we hear — in their own words — their reflections on what it meant day-to-day to accept the consequences of the decision that they and their families made to join this important litigation.

For those of us who are civil rights lawyers, these essays serve as a reminder that we must always be centered on the voices and needs of our clients. We work for them. They are not a means to an end. Good civil rights litigation is co-created with our clients. When civil rights lawyers do our job well, it means that we have created a platform and space in our legal system where the truth of our clients’ voices can be heard and understood.

I salute the authors in this collection and thank them for their willingness and enthusiasm in sharing, at long last, their stories in their own words.

Sherrilyn A. Ifill is the seventh president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Inc., the organization founded by Thurgood Marshall and which litigated Brown v. Board of Education.

This is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74 and funded The Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research to produce the new book Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)