Bipartisan Coalition’s New K-12 Climate Action Plan Says Net-Zero Schools, Infrastructure Changes are Key to Mitigating Climate Change

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

A new bipartisan coalition with some high-profile education leaders has released an action plan outlining how the sector can model climate change solutions.

Recommendations include ways schools can reduce carbon emissions, utilize infrastructure as a teaching tool, support communities of color disproportionately affected by weather crises and create pathways for students to pursue green jobs.

“Ultimately, there are a lot of technical fixes that we need in addressing climate change. But we will need people to actually advance a sustainable society,” said Laura Schifter, senior fellow with the Aspen Institute and founder of the new initiative, K12 Climate Action.

Synthesizing a year of listening tours and research, the report connects one of the country’s most sizable public sectors to actionable climate solutions — like mitigating warming effects by replacing the nation’s largest diesel fleet with electric school buses and swapping the common asphalt plots that surround schools with green spaces.

Organized by federal, state and local impact, all recommendations detail what partnerships can and do look like with business, philanthropy, media and advocacy organizations across the country.

In comparison with private homes, public safety offices and businesses, schools lead in the proportion of buildings producing net-zero emissions, according to the New Buildings Institute, a nonprofit that tracks and helps to redesign commercial spaces’ energy performance. Annually, K-12 schools in the U.S. produce emissions equivalent to 18 coal-fired power plants or roughly 15 million cars. Energy is the second most costly expense for school districts on average.

The K12 Climate Action commission of students, teachers, education administrators and environmental leaders includes incoming Chicago Public Schools CEO Pedro Martinez, researcher and president of the Learning Policy Institute Linda-Darling Hammond and the presidents of the country’s two largest teachers unions, representing roughly 4 million educators combined. The group is co-led by Republican Christine Todd Whitman, former New Jersey governor and head of the Environmental Protection Agency under President George W. Bush, and Democrat John King, former U.S. secretary of education under President Obama who is now running for Maryland governor.

With the action plan now live, the commission is coalition building with districts and businesses nationwide. Their focus is educating more leaders about how small and large school infrastructure changes or partnerships can support a cleaner environment, so that they’re able to follow through on recommendations.

“All the things that we’re calling for are achievable. There’s someplace somewhere that is doing each of the things we recommend,” King told The 74.

Some suggested changes, like improving air quality for students, are highly anticipated by parents and already underway in efforts to ameliorate pandemic health concerns. Beginning next year, more than 500 schools across New York state will further improve air quality, reduce emissions and add energy career and tech opportunities under Gov. Kathy Hochul’s just-announced $59 million ‘Clean Green Schools’ Initiative. New York officials are partnering with the New Buildings Institute on the effort.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers who sometimes clashed with King in her role as a labor leader, told The 74 that the union “leaped” at the opportunity to be involved in K12 Climate Action, seeing it as part of the AFT’s broader goal to make schools safe and healthy spaces for learning.

“The way you teach people is by not telling them, but having them see, feel, touch, use whatever senses they have to really envision a future,” she said.

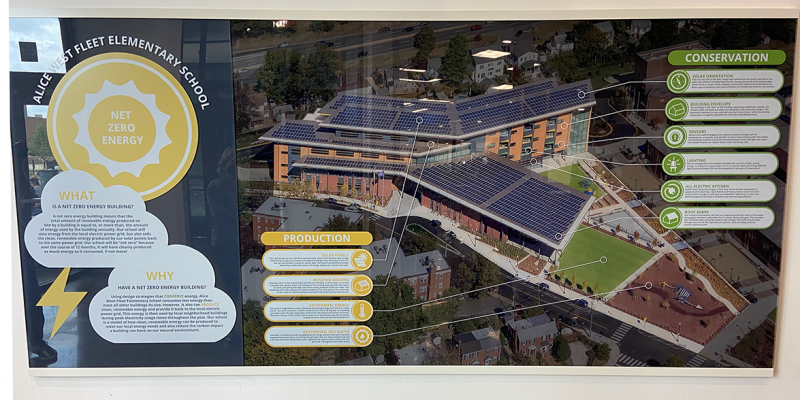

Weingarten and other commission leaders toured Alice West Fleet Elementary School in Arlington, Virginia Sept. 21 to learn how a small school has become a model of sustainability for the affluent, D.C. area county. The school’s geothermal heating system and solar panels save roughly $100,000 in energy costs each year, enough to fund two teachers’ starting salaries, according to the Aspen Institute’s Laura Schifter.

In the center of Alice West Fleet, the red and blue lights of a “solar pole” show students how much energy is being produced and used at any given moment. Any surplus goes to greater Arlington County, and upper grade students use data collected to make comparisons and predictions about how much energy will be produced at different points in the year.

On the first floor is the yet-to-be-named “Power Pole,” showing students the amount of power the school has generated. The blue is from the solar panels, the red is the power being used. Extra power goes back to the county. @AspenInstitute pic.twitter.com/er9XqMMJXk

— AFT (@AFTunion) September 21, 2021

Weingarten, whose enthusiasm was evident during the tour when she slid down a slide that connects Fleet’s third and second floors, added that the AFT recently established a climate task force, including members from states heavily dependent on the fossil fuel industry, like Texas, West Virginia and Alaska. The growing urgency to address climate needs across political parties and geography gives her hope that what unites us is greater than what divides us.

“Just like our responsibility to educate kids, there’s a responsibility to keep a climate that’s going to be there,” Weingarten said.

Commission member Nikki Pitre, executive director for the Center for Native American Youth, told The 74 that there’s also a responsibility to keep Indigenous people and values at the forefront of climate solutions, given that Native peoples have always stewarded the land and acted as environmentalists.

The action plan emphasizes that Indigenous communities’ knowledge systems — their local culture and ecological practices — must be included in climate solutions.

Pitre said she walked away from the tour of Alice Fleet questioning, “What do we need to advocate for in our policies to ensure that these schools are not the exception? That we’re providing equal access across the country — including tribal reservations, including urban spaces?”

School leaders on the commission say that equity considerations play a key part in deciding which sustainable infrastructure improvements are prioritized because solutions cannot be one-size-fit-all. For some districts, climate issues are just as urgent as addressing unfinished learning and mental health concerns related to the pandemic as families face unprecedented flooding in the South and upper Atlantic.

As Los Angeles County’s superintendent of schools, Debra Duardo leads the 80 districts and 1.4 million students that constitute the nation’s largest K-12 consolidated school system. She told The 74 she hesitated when first approached by the commission, given all the urgent challenges facing students during the pandemic.

“I hadn’t really placed as much of an emphasis on my own time and knowledge on understanding the impact that the education sector has on the environment. For me it was like, we’re super busy right now, but one thing this pandemic has taught us is that schools have to be ready to step up — that people look to schools as the hub of support and resources and communities,” Duardo said.

In Los Angeles, where families increasingly face poor air quality from smog and fire smoke, she said, it’s historically been student and environmental activists leading the charge for climate solutions. However busy leaders might be, she said, they cannot ignore the dread young people feel when confronting climate change and the strains it may place on their learning.

“There’s so much evidence and research that tells us that children thrive when they’re in an environment where it’s safe, beautiful and accommodating to meet their needs …Children aren’t going to learn and thrive in an environment if they don’t feel like anybody is listening, or they’re concerned that their futures, their safety are in danger.”

Advocates and teachers say sustainable school infrastructure presents a way to confront some eco-anxiety with positive actions and possibilities for future careers in engineering, green infrastructure and clean energy. K12 Climate Action commissioners contend that infrastructure changes are reducing emissions while preparing the next generation of stewards.

Sustainable changes also open the door for deeper civic and family engagement at a time when the pandemic has strained relationships to schools. As a part of a larger research assignment on the Chesapeake Bay, Ashley Snyder’s fourth-grade students at Alice West Fleet started brainstorming ways to share with the community how best to enhance rain gardens and filtration systems to protect the watershed area.

“I definitely see the students bringing home a lot more of what they’re learning to their families,” she said.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)