Bernie’s Billion-Dollar Education Plan: Sanders’s Proposal Would Dramatically Expand Magnet Funding to Integrate America’s Racially Isolated Schools. But Will It Work?

By the time two police officers dragged a young Bernie Sanders away from a 1963 protest in Chicago, America’s civil rights movement was in full swing.

Sanders, then a 21-year-old student at the University of Chicago, was arrested and fined $25 for resisting officers at a demonstration challenging racial segregation in one of America’s largest public school districts. Nearly a decade before, the Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in America’s schools was unconstitutional. In the more than 65 years since the Brown decision, integration has been hamstrung by public resistance and several subsequent Court rulings.

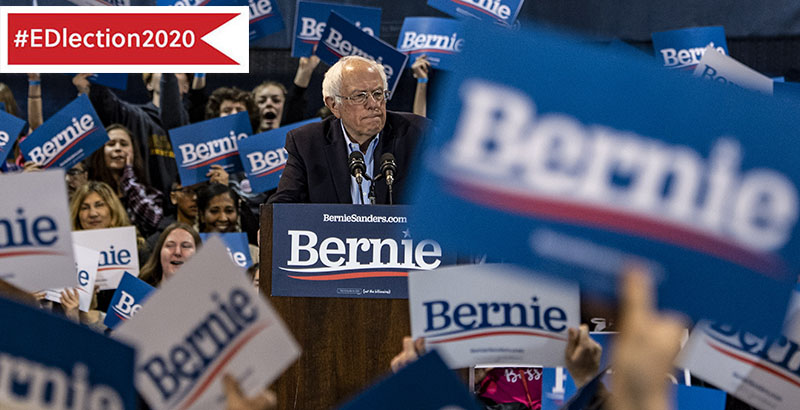

But the issue is re-emerging as a top concern for policymakers. And Sanders, now a 78-year-old senator from Vermont, has made school desegregation the top K-12 issue in his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination.

His education platform, released a day after Brown’s 65th anniversary and dubbed the Thurgood Marshall Plan for a Quality Public Education for All, seeks to pump $1 billion in federal money to magnet schools as a way to promote racial integration. The schools, which came to prominence in the 1970s, often offer specialized programs such as arts education to entice white families to enroll their children in integrated settings. The Sanders plan would provide nearly 10 times the current level of federal investment in magnet schools.

Though Sanders’s call to curtail the growth of charter schools has won him both applause and harsh criticism, his plan to significantly bolster federal investment in magnet schools, another form of school choice, has largely gone under the radar. The magnet schools plan is thin on details, and his campaign didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Richard Kahlenberg, director of K-12 equity at The Century Foundation, said he was encouraged to see school integration re-emerge as a leading education topic among Democratic presidential contenders following “decades of dormancy.” The Sanders plan “stuck in my mind as dramatic,” he said, after years in which many policymakers viewed the campuses as an antiquated “1980s concept.”

Yet roughly 4,300 magnet schools educate about 3.5 million students nationally, making them a leading form of public school choice and a primary lever to promote integration. They have been viewed as more politically palatable than court-enforced mandates like busing.

Kahlenberg is a leading proponent of magnet schools and has called on lawmakers to double federal spending on them to roughly $210 million.

“Sanders would take that even further,” he said. “I think it’s a healthy development.”

Support for magnet school programs, however, is far from universal, with some arguing they don’t adequately combat segregation and others challenging the value of integration outright. Others have questioned whether the schools are truly open to all children. Earlier this year, for example, a magnet school program in Hartford, Connecticut — lauded by Kahlenberg and other researchers as a national model — survived a lawsuit alleging that it relies on an unconstitutional “racial quota” to the detriment of the city’s black students.

Segregation ‘hasn’t happened by accident’

Though Sanders’s resistance to racial segregation dates back decades, his presidential bid has so far struggled to win the support of black voters. That includes those in South Carolina, where he unveiled his education plan last May. On Super Tuesday, Sanders got just 17 percent support from black voters in the state. Meanwhile, former vice president Joe Biden, who faced criticism early in the campaign because of his onetime opposition to busing, has emerged as a leading Democratic contender with strong support among black voters. Biden and Sanders are fighting it out for the top spot in a narrowing Democratic field as voters in six more states go to the polls Tuesday.

During the South Carolina rally, Sanders characterized school integration — by both race and socioeconomics — as an urgent problem, noting that America’s predominantly white school districts get roughly $23 billion more in funding than those in which students of color make up the majority.

Persistent school segregation “hasn’t happened by accident” but rather is the “direct result of policy decisions made in the courts and state legislatures and in Washington, D.C.,” Sanders said. “We cannot tolerate separate and unequal schools.”

The Sanders desegregation plan is ambitious and calls for federal lawmakers to triple funding for Title I, the primary federal investment in high-poverty schools. It also gives a position of renewed importance to federal courts, pledging to “execute and enforce desegregation orders and appoint federal judges who will enforce the 1964 Civil Rights Act in school systems.” In the decades since Brown, the Supreme Court has significantly curtailed desegregation plans, including those that require integration across school district borders. Most recently, in 2007, the court struck down school assignment plans in Seattle and Louisville that considered the race of individual students when creating integrated campuses.

However, the court found that efforts to avoid racial isolation are a compelling government interest and permitted policies that promote diversity that don’t explicitly weigh the race of individual students.

Magnet schools that promote diversity were designed as one weapon in the fight against school segregation, though research on their efficacy is mixed. A 2015 American Institutes for Research study on districts that received federal magnet school grants found that converting low-performing campuses with large shares of minority children to magnet schools reduced racial segregation but didn’t affect the concentration of low-income students. But at high-performing, predominantly white campuses, converting to magnet schools didn’t affect the concentration of students of color.

Meanwhile, a peer-reviewed study published last year in the Journal of School Choice found little evidence that magnet schools boost academic achievement.

Given the variation in magnet schools nationally, Kahlenberg of The Century Foundation said he supports the Sanders plan with one caveat: “so long as the program includes some tough accountability provisions to ensure that magnet schools will in fact produce economic and racial integration.”

Todd Mann, executive director of Magnet Schools of America, a trade group, shared a similar view. Though the “devil is always in the details” and Sanders has offered few details on his magnet schools proposal, Mann said, large cities across the country have relied on such schools to promote integration.

Rebecca Sibilia, founder and CEO of EdBuild, a think tank focused on school funding equity, is skeptical. Because school segregation often exists between school districts, she said, the Sanders plan fails to address the root cause of the problem. Rather than using magnet schools to encourage white students to attend classrooms in predominantly black schools, she urged a more politically divisive solution: Redraw school district boundaries in a way that creates equity.

“Sure, we should have more magnet schools,” she said. “But it’s not the systematic fix that our education system precisely needs right now.”

In Hartford, a model

Though magnet schools exist in most states, advocates often point to the program in Hartford, Connecticut, one of America’s poorest cities, as a success story. The Hartford region built a network of 41 high-performing magnet schools to promote integration after the state Supreme Court ruled in 1996 that racial segregation between Hartford schools and those in the more affluent suburbs violated the state constitution. The remedy includes the magnet schools and a program that allows Hartford children to attend suburban schools. Hartford’s magnet schools stand out from those in other cities because they draw students from multiple school systems, promoting integration across district borders.

Today, about half of Hartford students attend integrated schools, said Martha Stone, founder and executive director of the Center for Children’s Advocacy and an attorney who represented parents in the state desegregation suit. In January, plaintiffs and the state reached a settlement that expands the program and reforms how enrollment spots are awarded to students. Most significantly, Stone said, state officials agreed to devise a plan by 2022 to provide integrated schools to all students who want to attend them. In years past, demand has far exceeded supply.

That settlement also satisfied plaintiffs in a separate lawsuit, which argued that the program relied on an unconstitutional “racial quota” to enroll students. A newspaper investigation found that some black and Latino students were denied seats in order to maintain racial diversity on the campuses while a state-run lottery system gave a leg up to white and Asian applicants at campuses that struggled to attract them. The new plan adopts a lottery system based on students’ socioeconomic status. Oftentimes, people “get hung up” on race, but it’s important to recognize that magnet schools help alleviate the concentration of low-income students in schools because race and poverty are often correlated, Stone said.

But magnet schools in Connecticut have faced harsh criticism, including from parents who argue that they create a “two-tiered” system in which some students have access to the high-performing campuses while others remain trapped in struggling traditional public schools. Others have argued against integration altogether.

Among the critics is Gwen Samuel, founder and president of the Connecticut Parents Union, which filed a lawsuit against the state’s magnet school scheme. Rather than encouraging integration, she said, education leaders should focus their energy on improving educational outcomes within Connecticut’s traditional public schools.

“I’m concerned they’re using our magnet schools as a way to force integration, and I don’t think you should be forcing integration,” Samuel said. “It can happen organically with quality structures, period.”

Chris Stewart, a charter school proponent and CEO of brightbeam, a “nonprofit network of education activists,” questioned whether magnet school enrollment is truly open to all students. Pointing to Hartford, he argued that the schools are allowed to “discriminate on the basis of race, test scores and perceived ability, talent and capacity.” For example, he said, auditions to attend a magnet school that is centered on music education could be subjective.

But he also questioned whether integration can be achieved.

“History has told us time and time again that if white people wanted to integrate, they would have done it already,” Stewart said. “They don’t need inducements to make it happen. The problem with integration is not that Bernie Sanders hasn’t spent a billion dollars trying to make it happen yet.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)