As Trump Turns His Back on DACA Students, School in a Small Iowa Town Opens Its Doors to Immigrants

Postville, Iowa

Maynor Henriquez was only 5 years old when he moved to this small town in the American heartland, where the rolling cornfields and aging red barns offer a sense of security. Now an 18-year-old senior at the local high school, he still has a few memories of his home country: the coconut trees, the little creek that trickled by his grandmother’s house — and the time his uncle got shot.

Henriquez’s family had sent him to the U.S. to escape gang violence in El Salvador, and like hundreds of immigrants before him — some documented, some not — he found refuge in this unlikely corner of rural northeast Iowa. Others had arrived here fleeing war, stark poverty, and refugee camps, finding relative safety and stable jobs amid Iowa’s tranquil farmlands.

But President Trump’s decision Tuesday to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, has thrown Henriquez’s future — and that of thousands of students and teachers — into chaos.

Henriquez is a “dreamer,” one of some 800,000 immigrants who came to the U.S. when they were young and were granted temporary legal status as long as they were working or in school. Nearly half of them are students, and an estimated 20,000 are teachers, many of them too young to remember the countries where they were born. Now, they face the very real threat of being sent back to places they barely know. Henriquez, his classmates, and even their teachers may be arrested and deported, or they may simply flee, vanishing into the shadows.

For Henriquez, the thought of being forced back to El Salvador is disturbing. “It’s probably the last place I want to go,” he said. “There’s a lot of gang violence over there. That’s the reason I came here in the first place, to get a better life.”

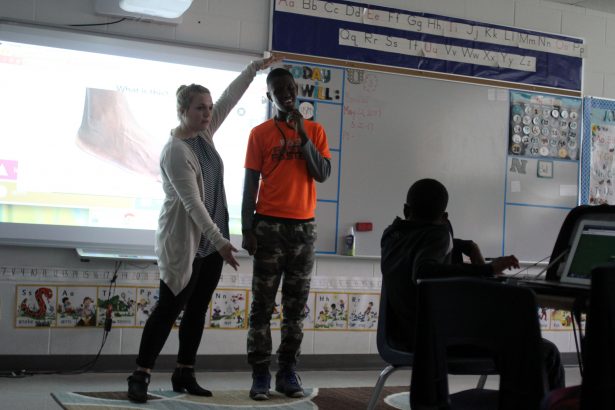

“These kids didn’t have a choice in coming here — it was their parents’ choice in coming here — and these kids are actually making something of their lives,” Joy Minikwu, an English as a Second Language instructional coach for the Postville school district, said of DACA. “Taking that away from them is almost inhumane.”

In the weeks and months leading up to Trump’s decision on DACA, educators from across the country were outspoken in calling for him to leave the Obama-era program in place. A petition signed by more than 3,000 public education leaders asked that he not rescind the program, particularly because many DACA recipients are bilingual and become teachers, filling “a tremendous need in a shortage area for many school systems.”

For Hanseul Kang, state superintendent of education in Washington, D.C., the issue is deeply personal. Born in South Korea, Kang came to the U.S. when she was 7 months old and didn’t learn until she was 16 that she was undocumented. She has since become a U.S. citizen, “But I still carry with me the fear and uncertainty of the years when there was no path forward,” she said. “Whatever you think about immigration policy, it’s not in our national interest to push our students into the shadows or to have them deported.”

The DACA decision was only the latest Trump policy to strike at the heart of Postville’s immigrant community. After the new president stepped up enforcement, rumors of arrests in a neighboring town sent waves of panic through Postville’s Spanish-speaking population, which in 2008 was devastated by a raid that at the time was the largest in U.S. history. And the town’s growing numbers of Somali refugees have been deeply affected by Trump’s ban on travel from six majority-Muslim countries, including Somalia.

The raid, which swept up about one-quarter of Postville’s 2,000 residents, caused lasting economic damage to the town and created a climate of fear that persists to this day. But rather than reduce the immigrant population, it has spurred even greater diversity, as immigrants from Somalia, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and Uganda have moved in.

Today, racial and ethnic minorities are a majority of the student population in Postville, making the town far more representative of the United States as a whole than the state where it is located. While more than 90 percent of Iowans are white and U.S.-born, there are an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the U.S., roughly 1 million of them under the age of 18. Additionally, about 4.5 million young people born in the U.S. have at least one undocumented parent.

The Postville district doesn’t ask students about their immigration status; 64 percent of its approximately 700 students are of color, and more than a third are learning to speak English as a second language.

In a political environment where undocumented children across the country feel victimized, protecting and improving the educational outcomes for Postville’s immigrant students — who often face language barriers, educational deficits, and trauma — is at the forefront of teachers’ minds.

Building supports

For a classroom filled with teenagers, Shelsea Baker’s question seemed remarkably rudimentary, but she knew at least a few students would be stumped.

“Ear, eyes, eyelashes, eyebrow?” she asked, pointing to an illustration projected onto her classroom’s SMART Board as she tried to teach 10 students, in grades 7 to 12, the English names for the parts of the body. “Uh oh, this one’s a hard one,” she said.

Students gasped, blurting out guesses in a flurry of foreign languages. On individual laptops, each student raced to pick the answer in English. The results were mixed, just as Baker predicted. The correct answer — eyebrow — flashed across the computer monitors, spawning another burst of commotion.

“Oh, only three people got this right,” Baker said.

“How do you say it in Somali?”

“How do you say it in Spanish?”

“Rolando, how do you say it in Mam?”

“K’iche’?”

Baker teaches English as a second language in the district’s newcomer program, providing the newest immigrant students with foundational language skills. Some of the teenagers in Baker’s class had stopped going to school in their native countries by third grade; others had never been to school at all. Many didn’t know a word of English before they immigrated to the United States, arriving at school with a range of native tongues, including the indigenous Guatemalan languages Mam and K’iche’.

“In my position I look like a rock star, because no matter what, my kids are growing,” Baker said. “I tell them all the time, ‘Let’s focus this first year just on, Can you have a conversation with me? Can I understand you and what you’re trying to tell me, and vice versa? All the academic stuff we can worry about on year two or when you’re in your homeroom.’ ”

Building on that program is a top priority for the district this year, Minikwu said, as the population of immigrant students continues to climb. The district hired two new ESL teachers this year, bringing the total to 10 and making it the district’s largest department.

The new immigrant students who fill the classrooms come with a range of challenges. Somali refugees, for example, often struggle to learn and retain phonics, Minikwu said — essential skills for sounding out words and learning to read — while Spanish-speaking students are reluctant to venture outside their clique.

“We have so many Spanish speakers here that they have a hard time challenging themselves to speak English,” Minikwu said. “That slows down their learning because they’re always relying back on their Spanish because that’s what feels most comfortable.”

For that reason, and because the district’s immigrant students often lag behind academically, Minikwu and other ESL teachers are working to further integrate them into mainstream classrooms. While the newcomer program caters to those with the most basic English skills, teachers in general classrooms are paired with ESL co-teachers to offer students grade-level content and language supports simultaneously.

“When they’re at a low level of language acquisition, they need to be pulled out because there are very specific skills we need to home in on,” Minikwu said. “As they progress in their language acquisition, it’s very important they get that grade-level content with those added language supports.”

But despite all the challenges Postville’s immigrant students face — like language barriers and fears of deportation — Baker said the hardest part of her job is becoming attached. The town’s immigrant students are often transient, leaving with their families beyond Postville for other communities across Iowa and the U.S.

“Because our kids are revolving all the time, it’s almost getting attached to the kids and seeing how much progress they’re making and not knowing where they’re going,” she said. “Or feeling like they’re going to a place that might not be as well equipped to help them.”

The Raid

Before Henriquez and other immigrants called Postville home, the town resembled most other places in Iowa. But when a group of Orthodox Jews from New York City opened a kosher meatpacking plant on the edge of town in the 1980s, everything began to change. The plant helped shape Postville into an enclave of multiculturalism — a sign on the edge of town greets visitors to the “hometown to the world” — where a kippah or a hijab are about as commonplace as Wrangler blue jeans.

That very plant, which brought economic opportunity, also brought Postville to its knees.

In the final weeks of the school year in May 2008, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents stormed the facility in black flak vests as workers scrambled to the screams of “La migra, la migra.” Kelsey Mucia, a high school junior who was born in Iowa, said her mother — a Mexican immigrant who had documents to work in the U.S. legally — was caught up in the drama. As agents stormed the plant, undocumented workers asked Mucia’s mother for help.

“There were several women who would just tell her to take care of their kids because they knew they were going to be gone, there was no way they were going to get their kids,” she said. Following the raid, 19 children hid for weeks in the basement of Mucia’s house. “They just wouldn’t go outside,” she said. “They were too terrified.”

In total, 389 people, mostly Guatemalans, were arrested and held at a cattle exhibit hall in nearby Waterloo. Within days, 300 workers were convicted of using false Social Security numbers, sent to prison, and eventually deported. Ultimately, one-third of the town’s residents vanished.

Even today, Henriquez and other older students remember that chaotic spring morning — most vividly, the sound of helicopters overhead. A normal day at school, sitting at a desk in class or playing hopscotch at recess, was interrupted by cell phones buzzing with the news.

As word of the raid spread throughout the town’s schools, students were brought to the high school auditorium, where school staff checked kids out as their parents picked them up. For many, no one came; those who remained were bused to St. Bridget’s Catholic Church, which quickly became a makeshift sanctuary for children and their families. Henriquez said he hid with his family at a nearby chicken farm.

Now, with Trump in the White House, memories of that Bush-era raid have come rushing back. When Postville residents heard in March that federal agents had apprehended an undocumented immigrant in a neighboring town, rumors of ICE sightings in Postville began to surface. Some parents pulled their kids out of school, fearing they might be picked up on their walk home. One school official said his undocumented mother barricaded the front door and hid inside her house. Others packed their bags and fled town.

The high school principal caught wind of the crisis and contacted immigration enforcement, explaining in an announcement over the school intercom that no enforcement activity had been confirmed in Postville. But the damage had been done.

Embracing community

Nearly a decade after the raid took a devastating toll on Postville, Minikwu said the community is finally making a comeback. However, residents from neighboring towns look down on Postville students, and Henriquez said that since Trump was elected, he’s experienced an uptick in racial profiling.

But Postville students and educators alike see the town’s diversity as an asset. Tim Dugger, the district superintendent, said he spends a good amount of time dispelling misconceptions about the town and Postville’s schools, where enrollment has continued to tick up for the past five years.

“The one thing that I was kind of expecting was more conflict between some of the cultural differences, with the kids and whatever culture they came from,” Dugger said. “What I found is the complete opposite: I found a lot of acceptance here, and that goes for any background, any religion, any culture. They get along and they exist together.”

As a swath of Postville students become a target under Trump’s immigration agenda, Postville school officials embrace their obligation under federal law to educate all children — regardless of immigration status.

“My biggest motivator is just hearing these kids’ stories and seeing their drive to better their lives,” Minikwu said. “It’s just incredible what these kids come from and the experiences they’ve had, and yet they have positive attitudes and are working hard.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)