As Teacher Evaluation Reforms Come Undone, 2 States React Very Differently to Using Test Scores to Rate Educators

Updated, Oct. 29

A decade ago, states across the country were tripping over themselves to reform their teacher evaluation systems. With the U.S. Department of Education dangling millions of dollars in Race to the Top funding as incentives, dozens of states started incorporating student test scores, increasing the frequency of classroom observations and multiplying the number of categories on which they rated teachers.

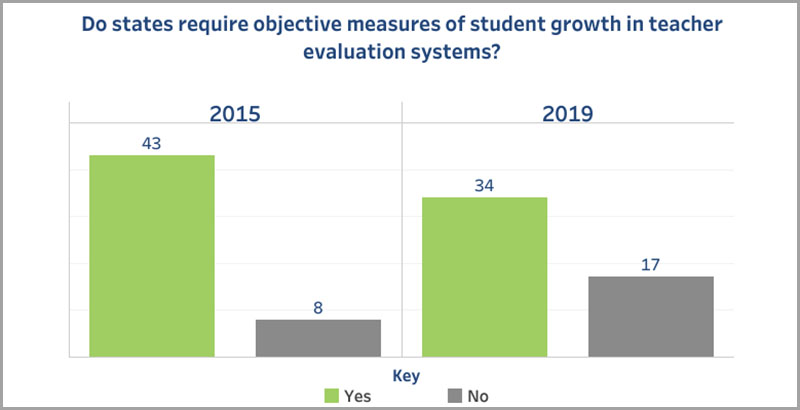

Now, with the carrots gone and the Every Student Succeeds Act the law of the land, states are methodically unwinding those changes. The National Council on Teacher Quality released a report earlier this month showing that 22 states and the District of Columbia have pulled back at least one of the changes they made between 2009 and 2015. Eleven states no longer require teacher evaluations to include standardized test data. Ten states have eliminated their requirement for teacher evaluations to include objective evidence of student learning. And after five more states required that their teachers be evaluated annually, the breakdown has returned to where it was eight years ago, with 22 states mandating yearly teacher evaluations and 29 not.

“We are disappointed that states aren’t even maintaining the systems that will enable them to identify which teachers are effective so that they can help make sure that some of our most vulnerable students will have consistent access to these great teachers,” said Elizabeth Ross, a managing director at the National Council on Teacher Quality and the lead author of the report.

The shifts are a result of changing political and economic environments as well as challenges that emerged as some of the rapidly adopted reforms began to be implemented.

In New Mexico, the state replaced a system in which 99 percent of teachers met the standards. The new system originally counted student test scores for half of a teacher’s evaluation, and in the first year, 2015, 73.8 percent of teachers were rated effective or better. That year, several dozen teachers burned their evaluations to protest the new system.

As happened in many states, teachers unions pushed back, suing the state education department. In New Mexico’s 2018 gubernatorial race, undoing the evaluation system was one of the few areas of agreement between the Democratic and Republican candidates. Democrat Michelle Lujan Grisham won the election and jettisoned the system on her first day in office by signing an executive order.

Edward Tabet-Cubero is among the 46 members of a task force the governor created to redo most of the teacher evaluation system. A former teacher and district administrator who now leads the Learning Alliance of New Mexico, a research and advocacy nonprofit, Tabet-Cubero is relieved to be rid of what he saw as an overly complex system that tried and failed to capture teachers’ impact on student test scores.

“It completely decimated public education in New Mexico. It pushed thousands of teachers out of the classroom, and we’re now trying to recover from that,” he said, citing a December 2018 state Legislative Finance Committee report showing 3,033 teachers left the profession in 2015 and that number grew by another 1,000 between 2016-18. “Teachers want accountability and they even want accountability around student outcomes, but they want that system to be accurate and fair, and I think that’s what the current administration is going to do.”

While many states are walking back some of their recently adopted reforms, some changes still largely hold. For example, the number of states requiring more than two rating categories in their evaluation systems rose from 17 in 2011 to 44 in 2015 and remains at 41 today, according to the National Council on Teacher Quality report. Similarly, 37 states currently require all or some of their teachers to be evaluated multiple times, barely down from the 38 states who did so in 2015 and still well above the 20 states who fell into that category in 2011.

Texas was one of only two states that added student test scores to its evaluation system since 2015 (Alabama was the other). Republican state Sen. Larry Taylor, who chairs the state Senate Committee on Education that approved the changes, was unapologetic about instituting a more aggressive system of sorting teachers.

“I really don’t want a bad teacher in any classroom in Texas,” Taylor told The 74. “If it’s apparent that some teachers’ gifts and talents lie somewhere else, I’d rather them go somewhere else and not occupy a classroom. I’d rather have good teachers in every classroom. So if we lose teachers who really aren’t proficient at that job, that doesn’t hurt my feelings.”

Looking back on the past decade, Ross, of the National Council on Teacher Quality, believes that supporters of the reforms missed opportunities to cement the changes. More training and collaboration with the educators conducting the evaluations could have helped, she said.

Ross also noted that the more rigorous Common Core State Standards were introduced during the same period when many changes to the teacher evaluation system were adopted. Despite a similar backlash, the majority of states that adopted the standards still rely on most or all of them. She thinks there is a lesson to be learned by the proponents of transforming teacher evaluations.

“I think that individuals working on the Common Core were quite smart and were quite savvy about continuing to communicate about the potential impact, the positive impact of these higher standards for students,” she said. “I think, in the educator evaluation space, there was less of a consistent communications effort, which enabled it to be dominated by a great deal of heat and not a lot of sunlight.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)