As More DCPS Schools Open, Many Black Parents Keeping Kids Home

Update Feb. 1: D.C. Public Schools announced Sunday night classes would be all virtual Monday due to snow.

Thousands of students are expected to return to D.C. Public Schools Monday— but in predominantly Black wards disproportionately bearing the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic, parents are keeping kids home.

The school district for months has underscored the urgency of reopening schools to serve those “furthest from opportunity” who have struggled with remote learning. Chancellor Lewis Ferebee has also touted how DCPS has “grounded [itself] in very rich community engagement … to create an opportunity for more voice and input.”

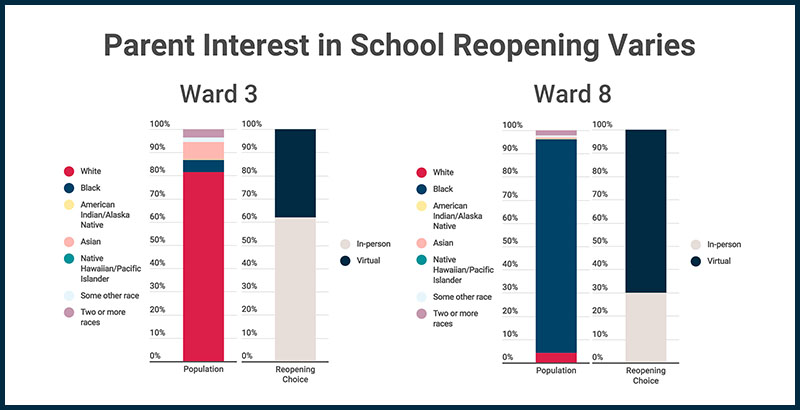

Yet similar to nationwide trends, recent district data suggest many families in Wards 5, 7 and 8, majority Black neighborhoods with higher concentrations of poverty and signs of disparate learning loss, aren’t intending to send their kids back yet as the pandemic continues.

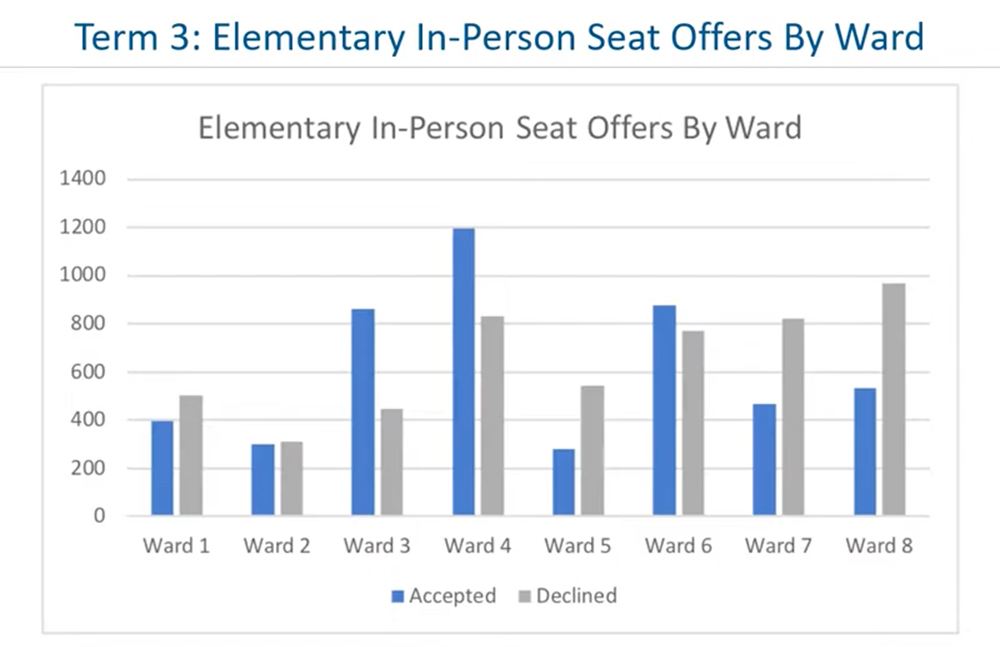

As of early last week, about one-third of seats offered at elementary schools in those wards had been accepted, according to DCPS data — while nearly two-thirds of seats had been snagged at schools in the whiter, more affluent Ward 3. (While D.C. students often attend schools outside of their ward, experts noted the data were still revealing, as the majority of students living in Wards 3, 7 and 8 do attend a neighborhood school).

“I know the city, in particular DCPS, is holding forums and town halls, but something’s not landing,” D.C. State Board of Education president Zachary Parker told The 74. “Many parents … are still not trusting what DCPS is sharing.”

Districtwide, 8,000 elementary and secondary school students have accepted in-person seats starting Monday — just over half of the district’s available capacity — though the teacher’s union legally challenged DCPS’ readiness. That number marks a sizable jump from the 900 students DCPS has served previously in CARE classes.

Parents in majority-Black neighborhoods, who expressed similar hesitance to in-person options in December parent surveys, have cited various reasons for wanting to stay virtual. Many are afraid: Black D.C. residents make up about 45 percent of the population but 74 percent of the city’s COVID deaths. Some, despite DCPS’ school safety checklists, aren’t confident their school is safe, pointing to past instances where basics like hot water and soap were unavailable at their kids’ school.

The intensive focus on reopening “really frustrates me,” Ward 7 parent Patricia Stamper said. DCPS “surveyed the parents, the parents told you, ‘Hey I want to stay home.’ … And you’re like, ‘Nah, we’re going to open the schools.’ What?”

Ferebee emphasized at a recent D.C. Council hearing that reopening is serving students in high-needs categories, with about 43 percent of those accepting seats considered “at-risk” — a designation that includes foster and homeless youth and those whose families qualify for public assistance — compared to 47 percent citywide.

Some parents keeping kids home have told officials it’ll take steps like vaccinations, smaller classroom sizes and “significantly fewer” positive COVID-19 cases before they’ll consider coming back to buildings. So the question now, for many families and advocates, is what the district is doing to ensure learning improves not just for those able to return in-person, but for those who can’t.

D.C. public school students in Wards 7 and 8 especially have shouldered much of the social-emotional and academic consequences of the pandemic. They attained 49 percent of expected growth in English language arts from fall 2019 to fall 2020, according to an EmpowerK12 report. Students across other wards averaged 110 percent growth in ELA.

“Many of the children who will supposedly benefit from in-person instruction need high quality distance learning” instead, Ward 8 mom Allyson Criner Brown wrote in a statement to the D.C. Council. “What targeted support has DCPS done for these families besides rushing to reopen the schools?”

Meeting Families’ Needs

Ferebee is adamant that this “is not a system that is solely focused on in-person programming.”

There will “continue to be investments in virtual learning,” he told reporters at a Jan. 26 media roundtable, adding that DCPS is “on pace to provide high-dose tutoring to students” who have fallen behind and has a February professional development session scheduled for principals and staff to continue refining virtual skills.

Quality distance learning means many things for parents: Conducting regular phone calls and surveys. Supporting trauma-informed training of staff. Ensuring students have basic supplies like notebooks, markers and books. Having a “simple” process for families to get additional devices or repair devices as needed.

Responsibility extends to D.C. government, too, parents like Brown added. If D.C. prioritizes initiatives like rent relief, citywide high-speed Internet and jobs protections, parents can better “support children in distance learning,” she wrote.

Meeting families where they’re at, Ward 7 parent Elizabeth Reddick said, is critical as the district pushes forward on reopening schools and looks to next school year. It builds trust.

While Reddick’s 10th grader at Bard High School Early College has chosen to stay virtual for Term 3 — she’s felt productive and less stressed at home — Reddick would’ve been OK with her returning. And that’s because her school’s principal has been transparent and attentive, with continuous parent polling and an “open door” policy.

Schools “have to change the mindset” of what it takes to get parents’ buy-in, she said. Many seem “so worried about getting the parents’ ‘engagement’ they’re not even thinking about: OK, do all of my students have access? Do the parents understand how to access the different platforms?”

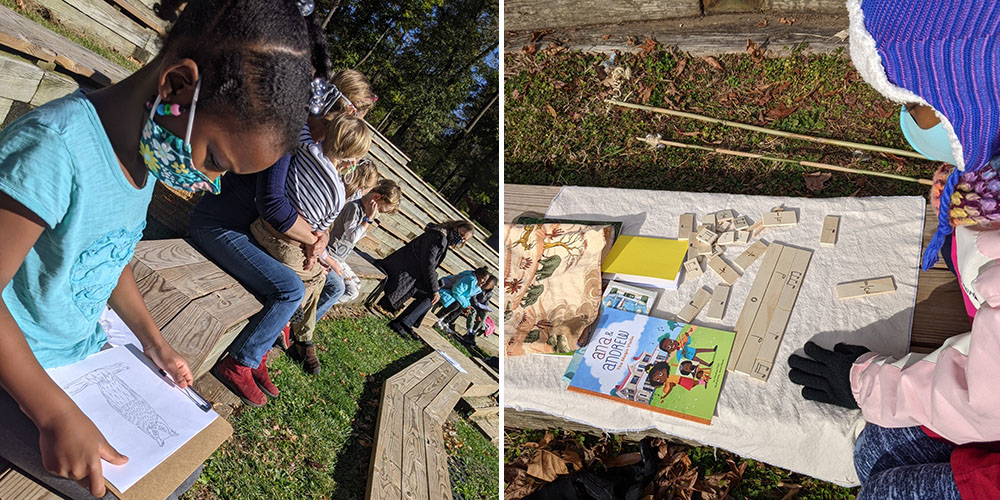

Beyond the computer or classroom, some advocates and parents also want more outdoor learning opportunities. The D.C. State Board of Education recently sent a letter to Mayor Muriel Bowser requesting at least $4 million in funding for interested schools.

A few DCPS schools, like Tyler Elementary in Ward 6, have already baked in outdoor learning as they’ve reopened. Ferebee has said he doesn’t view outdoor learning as a “silver bullet” — students still have to use restrooms and weather is unpredictable — but he told the D.C. Council Jan. 21 “if principals have interest in resources [for outdoor learning], we will follow up” with them.

Brenda Richardson, who helps run a monthly learning program at Oxon Run Park in Ward 8, can attest for parent and student interest in outdoor programming.

About 60 parents and children have attended three meetups since late fall, gathering at the park’s amphitheater and using tools like six-foot sticks to socially distance. There was a raptor presentation with live birds. A storytime. A cello player and percussionist who taught kids — bundled up in scarfs and mittens — math, through song and puzzles.

“It’s demonstrated that you can learn outside, connect with school and also connect with nature in a very significant way,” Richardson said. And “clearly there’s an interest … parents show up.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)