As Indiana’s Foster Care Population Rises, New State Data Reveal Troubling Outcomes for Students — but Questions Remain About Whether These Numbers Tell the Whole Story

With the number of foster youth rising nationwide, Indiana just released one of the most detailed reports on how well these students do in school. That makes the state a leader as federal law this year now requires all states to report academic data for these students, and many have yet to comply.

Indiana’s report, which includes more than is federally required, confirms just how challenging it is for students in foster care to receive a good education. This first-of-its-kind data set for Indiana finds that graduation rates for these students are more than 20 points lower than the state average and they are falling far behind in reading and math. These students also face high rates of discipline and are more likely to attend failing schools.

But even these dire data points might miss the mark for the true educational outcomes of students in foster care. Advocates say that the state could be undercounting the number of students in foster care by half.

Students in foster care who are in special education or a racial minority perform even worse than their peers. Among the report’s findings:

● 64 percent of students in foster care graduate from high school, compared with 88 percent of all students.

● 1 in 5 foster youth don’t have to meet all the requirements for graduation to receive a diploma, and fewer than 1 in 10 graduate with academic honors.

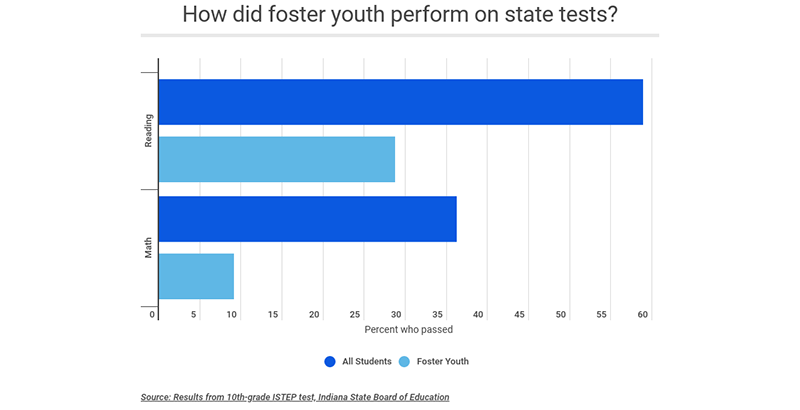

● Only 9 percent passed their 10th-grade state math test, while 28 percent passed in reading.

● 3 percent of black students in foster care passed the 10th-grade math exam, and 15 percent passed reading.

● Students who are in both foster care and special education have the lowest pass rate on the state test, at 1 percent and 6 percent in math and reading, respectively.

“I’m heartbroken for these kids, in all honesty,” Indiana House Education Committee Chairman Bob Behning (R-Indianapolis) said in an interview with The 74. “When you see the data and the travesty that is going on in their lives and see the unfortunate education opportunities, or lack thereof, it is even more disheartening.”

Indiana is required under a 2018 law to compile an annual report and remediation plan for students in foster care.

But the number of students included in the new report falls short of other data sets, making it unclear just how accurate these numbers are. Advocates said this could mean an underrepresentation of how well students are actually doing on state tests or to what extent they are being disciplined.

“For children in its own care and custody, the state of Indiana doesn’t know where half of them go to school, they don’t know their graduation rate, they don’t know if they’re on track to graduate,” said Brent Kent, CEO of Connected by 25, a nonprofit that supports foster youth and that pushed for this data collection.

The report claims that there are nearly 9,000 public school students in foster care. But the report also cites and links to a state data book that finds that 31,000 children were in foster care during 2017. Of course, not all these children are students. A little over one-third are under age 4, and 0.2 percent are 18 and older. But even accounting for that leaves between 17,000 and 20,000 children who are school age. The state agencies said that their data reflect all students who were in foster care during the academic school year. Yet eliminating students who could have exited and entered the system during the summer months leaves several thousand students missing from the state report. Federal data reported in the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System confirms that nearly 32,000 children were in the Indiana foster care system during the 2017 fiscal year.

The 74 reached out to the Department of Education, the State Board of Education and the Department of Child Services, and although they said they worked together to confirm the number of students in foster care, none could fully explain why their data set didn’t align with other, larger counts of students in foster care. A Department of Education spokesperson reiterated what is written in the report: Because this is the first year of data collection, there is “less consistency” in these numbers and these numbers don’t include students in private schools.

While accuracy questions remain, the report provides one of the largest releases of data from a state on the educational outcomes of its foster youth. The Every Student Succeeds Act required that states publicly report the graduation rates and test scores of students in foster care, but Indiana tried to go a step beyond with its data collection, requiring schools to share grade retention, suspensions and whether these students attended failing schools.

Kent said he and his organization proposed the new law because they were disappointed by how little ESSA required the state to share on foster youth. With more robust data, advocates said that the state can do more to help students in foster care.

“Why aren’t we paying attention to our most educationally vulnerable population?” said Demetrees Hutchins, an institutional education researcher who had been in foster care. “As foster youth, we’re pretty much on our own in the school system and we’re on our own in the foster care system.”

Indiana has seen one of the largest increases in its foster youth population, which has jumped from 18,000 children in 2012 to 32,000 in 2017. Some argue that the opioid epidemic is partially to blame, as the number of youth in foster care nationwide has also increased in recent years.

Students in foster care face serious academic challenges that come from switching schools as they transfer homes, miss class for court appointments and experience the trauma of being removed from families. National data show that these students have an average seventh-grade reading level by the time they are high school seniors and are three times as likely to be expelled as their peers. While ESSA was meant to provide some public reporting on the education outcomes of these students, an analysis by The 74 found that many states are lagging behind in publicly sharing these statistics.

Because of this report, Indiana knows some data points many states don’t. Other findings include:

● 20 percent of foster youth are suspended from school, compared with 8 percent of all students.

● Expulsion rates are less than half a percent, both for students in foster care and all students.

● Students in foster care attend failing schools at a higher rate than all students — 17 percent, compared with 10 percent.

● Most foster youth — 37 percent — attend schools rated “B,” followed by 22 percent who attend “C” schools and 18 percent who attend “A” schools.

In response to the data, the state Department of Education is required to create an education plan to improve the educational outcomes of foster youth, a plan that will be presented to the board of education on June 30. A department spokesperson said the process to create this plan will include feedback from groups involved in the foster care system, such as the Indiana Youth Institute and the Indiana Association of Resources and Child Advocacy. The department’s goal is to have the plan ready for schools to act on by the beginning of the 2019-20 academic school year.

“As this is the first report of its kind, and subsequent plan, we understand the importance of making sure we have all the right faces and voices at the table,” Adam Baker, a spokesperson for the Indiana Department of Education, wrote in an email to The 74. “Having the right data is also important, and whether one student or 1,000 students, each student deserves the necessary support and resources to be successful. Once the plan is developed, it will be important we support schools to carry … out recommendations from the plan.”

Advocates hope the plan includes input from foster youth. Joshua Christian, who spent 18 years in the foster care system and now advocates for his peers in Indiana alongside groups like Connected by 25, suggested that more tutoring could help foster youth keep up in school. Reading was a challenge for Christian as he moved between schools, and he said he still struggles with grammar.

“At the end of the day, it’s the state putting the young person in foster care, so they are the guardians of them,” Christian said. “Ultimately, they’re responsible for the outcomes.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)