Analysis: Summer Learning Is More Popular than Ever. How to Make Sure Your District’s Program Is Effective

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

By now, it’s well-established that children have suffered substantial academic losses during the pandemic, and most so for students in high-poverty schools, students of color, and low performing white students.

Acknowledging the COVID-19 learning interruptions and the fact that summertime is an opportunity in and of itself, the federal government and districts across the country are finding ways to support students in moving ahead between school years. In a nationally representative survey we fielded in November 2021, 86 percent of district leaders said one or more of their schools had offered a program in summer 2021, compared with 57 percent in summer 2020. Urban and suburban districts were more likely than rural ones to offer summer programs in both years. In 2021, however, there was also a large increase in summer programming offered by rural districts. Other data also supports our finding that summer learning is a popular academic recovery strategy.

Districts planning such programs are doing so for good reasons. Evidence shows that students can and do benefit from summer programming. The most comprehensive evidence to date comes from our National Summer Learning Project, a longitudinal, multidistrict randomized controlled trial that evaluated five-to six-week voluntary academic summer learning programs. We followed more than 5,600 third graders in Boston; Dallas; Duval County, Florida; Pittsburgh; and Rochester, New York, from 2013 through 2017.

The project was designed to understand whether and how school districts and community partners could run these programs to serve large numbers of students; whether there would be demand for them; the effect of consecutive summers of programming on student outcomes; and the persistence of effects over time.

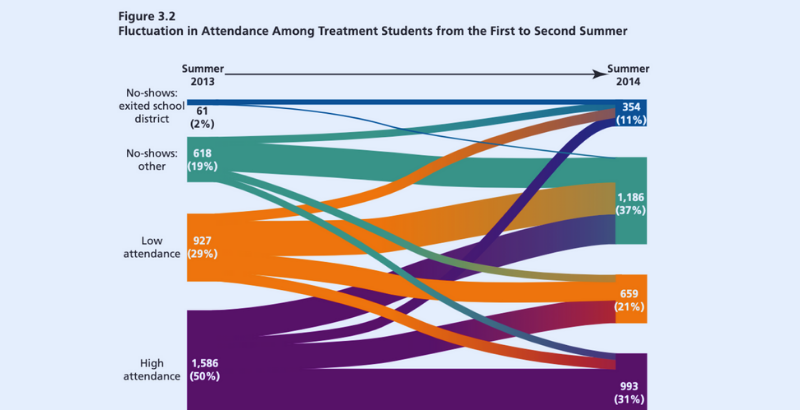

It turns out that attendance is the key. We found that students who attended the program at high rates (for at least 20 days) scored better on mathematics assessments in the fall than control group students, and those effects persisted through spring. After two summers of programming, students with high attendance outperformed the control group in both math and reading in the fall and on subsequent spring state exams.

In the best of times, it is no small feat to put together a quality summer learning program that can produce these outcomes. Given that districts are focusing not only on academic recovery, but on retaining teachers, supporting students’ and teachers’ mental health and addressing increases in misbehavior, they need immediate, digestible guidance for summer programming.

Based on our study of districts’ summer programs, we developed over 50 recommendations for implementation. Chief among them:

Plan now. Comprehensive early planning reduces logistical problems and increases instructional time. In addition, smooth operations, which are likely to result from good planning, support a positive site climate, which is linked to increased attendance. Districts should name a summer director who works to plan the program at least half-time as planning is practically impossible without dedicated time and resources.

Start developing the curriculum. Summer programs are short. Districts need to provide teachers with well-organized curricular materials that include lesson plans aligned with student needs and school-year standards, and allow for options for a range of activities to address different levels of knowledge and skills. Pre-program training that includes hands-on practice with the materials prepares teachers to use the curriculum effectively.

Offer at least three hours of academics a day for at least five weeks. Voluntary programs aiming to improve both math and reading should operate for at least five weeks over the summer to maximize the probability of producing measurable academic benefits. Our systematic evidence review found that no program running for fewer than three weeks produced significant academic benefits.

Promote consistent attendance. Students need to attend at high rates to demonstrably benefit from a summer program. Strong attendance is associated with a positive site climate — the norms, goals, values, relationships, and teaching and learning practices that drive students’ daily experiences and enjoyment. In our study, daily attendance ranged from 65 to 92 percent. The one factor that was correlated with attendance was site climate; programs with lower absenteeism had an inclusive and friendly environment, strong engagement and positive interactions between adults and students.

Build new skills and interests. Children from families experiencing poverty are less likely than peers from families with higher incomes to engage in informal enriching experiences such as visiting the beach, zoo, aquarium or an amusement park during the summer. Further, children and youth from higher-poverty communities have less access to safe play spaces and fewer opportunities to participate in outdoor physical activities, and are less likely to play on a youth sports team than peers living in higher-income communities. Summer programs can offer activities like swimming, field trips, theater and cooking to expose students to new activities and help them develop new skills. These activities can also support attendance goals, as students look forward to coming back each day.

Hire the best teachers. Teacher quality has the largest school-based impact on student outcomes. Hiring certified academic teachers with relevant grade level and subject experience will enhance student learning. In addition, specialized staff who support students who have additional needs — such as English learners, students with Individualized Education Plans, and those needing behavioral or mental health support — will enhance learning and ensure continuity of support from the school year..

While we applaud the nation’s school districts in creating summer learning program opportunities, those programs must offer quality experiences. Doing so is both challenging and essential.

Catherine Augustine is a senior policy researcher at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation, with 20 years of experience conducting education research. She is also a professor of policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School and director of the RAND Pittsburgh Office. Heather Schwartz is a senior policy researcher at RAND.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)