Analysis: Pandemic Learning Loss Could Cost U.S. Students $2 Trillion in Lifetime Earnings. What States & Schools Can Do to Avert This Crisis

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Over the past two years, virtually every American has suffered loss. Many have lost loved ones. Others have lost jobs or homes. In most instances, the only option is to accept fate and try to return to a sense of normalcy.

However, when it comes to addressing students’ learning loss, we must resist the temptation to try to get back to normal. Returning to a normal school routine, without addressing lost learning opportunities, would leave millions of students permanently behind. Doing what’s right by kids will require a massive national effort — over and above what’s considered normal — to provide additional instructional time over the next two years.

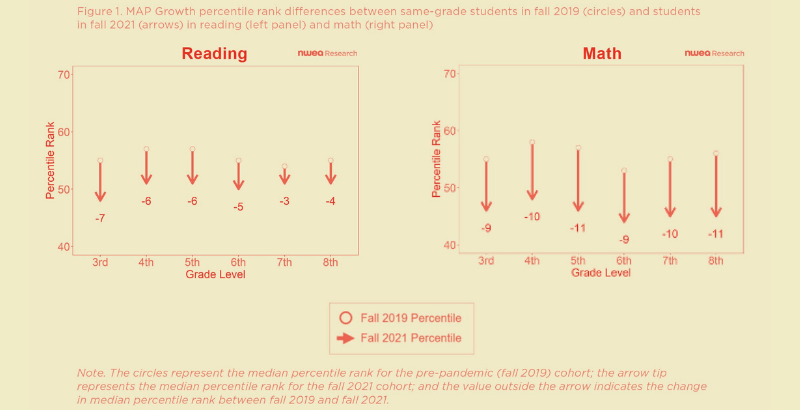

It’s difficult to convey the magnitude of students’ learning loss in a manner that galvanizes action. This week, the nonprofit testing company NWEA reported that the median student in grades 3 to 8 returned to school this fall 9 to 11 percentile points behind in math and 3 to 7 percentile points behind in reading. For most people, such numbers fail to convey the magnitude of the loss and the scale of the effort needed to address it. It’s like hearing that the price of gas is rising, denominated in Albanian leks or Algerian dinars.

One way to make the magnitude more tangible is to restate the loss in terms of students’ future earnings. Using the relationship between achievement test scores and earnings among those already in the workforce, a 9 to 11 percentile point decline in math achievement (if allowed to become permanent) would represent a $43,800 loss in expected lifetime earnings. Spread across the 50 million public school students currently enrolled in grades K to 12, that would be over $2 trillion — about 10 times more than the $200 billion Congress set aside last year to help schools respond to the pandemic.

Another way to express the loss is in terms of typical academic growth per week during a normal school year. In grades 4 and 5, it would take an additional eight to 10 weeks of instruction to cover the loss in reading and math, respectively. In grades 6 through 8, where the material is more complex and students’ rate of progress slows, it would take an additional 14 and 19 weeks of instruction to cover those losses in reading and math, respectively.

Schools could compensate for that deficit without literally extending the school year: with tutors, extra periods of instruction in math and reading, Saturday academies and afterschool programs. However, no one should expect to produce the equivalent of eight to 19 instructional weeks just by asking teachers to run a few review sessions and to generally pick up the pace. Yet, for most students, that’s what the academic catchup strategy seems to be so far.

Here’s a more disturbing fact: A large body of evidence is showing that students in high-poverty schools, students of color and white students who were scoring below grade level before the pandemic have lost the most ground academically. Perhaps most surprisingly, those white and Asian students who were scoring in the top quartile before the pandemic have returned to school this fall on track — with no loss in expected growth — as if there had been no pandemic! In other words, communities of color and those experiencing poverty have not only borne the brunt of job and wage losses, but their children have borne the brunt of the academic losses as well.

In many places, local schools are still bogged down with immediate concerns, such as whether to require masks, whether to shut down in the face of COVID outbreaks and how to get back to normal. Federal and state policymakers can help, by requiring local leaders to look down the road and begin planning more ambitious catchup efforts for this summer and next school year.

To start, states should quantify the magnitude of pandemic learning losses. They should suspend their old accountability measures and replace them with specific targets for each school and district to bring students back up to their pre-pandemic performance by spring 2024 — as a floor, not a ceiling. For the next two years, all eyes should be focused on getting students back to pre-COVID academic levels.

Second, state governments should be preparing to target their remaining federal dollars to schools and student groups with continuing achievement losses. Last spring’s American Rescue Plan required states to allocate 90 percent of the new federal dollars using established formulas — but that was before anyone knew which schools and students had lost the most ground over the past two years. States should hold back much of the remaining 10 percent until the achievement data clarify which students are still lagging behind.

Third, education leaders should use this summer and next fall to track the efficacy of their recovery efforts. The federal government is largely to blame for the absence of a learning plan; it did not specify which data districts should be collecting. In the coming months, the Biden administration should provide guidance to districts about tracking the attendance of students in each type of intervention and linking those data with student outcomes.

Local leaders must be prepared to update, adjust and expand their academic recovery efforts over the next two years. To do that, they will need to know which students are engaged in each type of intervention and which approaches are associated with the largest achievement gains.

Our research team is working with 12 large public school districts to compare the achievement growth of students receiving various types of interventions, from tutoring to Saturday academies to afterschool programs. We are proud that our district partners — even without federal guidance — foresaw the need for better tracking so they could adjust their plans by scaling up their most effective programs. We will be sharing what we learn as we go.

Teachers, parents and students are exhausted. Even if their schools return to a normal schedule, most students will remain behind at the end of the current academic year. But rather than wait for next spring’s state tests to confirm that news, local school districts should be planning now to ramp up their catchup efforts this summer and next fall — to provide supplemental instruction at a scale necessary to make students whole. Meanwhile, state and federal governments should make sure they have a plan in place to determine which local interventions are making the most difference, and to share what they are learning with local decisionmakers. If we do not act decisively now, if we try simply to get back to normal and allow these learning losses to become permanent, we will be solidifying what’s been a dramatic increase in educational inequity.

Dr. Dan Goldhaber is director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research. Thomas J. Kane is the Walter H. Gale Professor of Education and Economics at Harvard University and faculty director of Center for Education Policy Research, which works with school agencies through its Strategic Data Project, Proving Ground, National Center for Rural Education Research Networks and other research projects. Andrew McEachin is director of the Collaborative for Student Growth at NWEA, a nonprofit assessment provider.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)