Analysis: COVID-19 Raised Fears of Teacher Shortages. But the Situation Varies from State to State, School to School & Subject to Subject

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

There’s been a recent wave of stories in the media, amplified on social networks, stating that the U.S. could face a major teacher shortage as the pandemic draws prospective educators away from the field. These articles raise concerns that we ought to take seriously, but they also perpetuate some misunderstandings about teacher shortages.

The stories rely largely on anecdotes from individual teacher education programs, states, schools and prospective educators, making the case that relatively low pay, a booming private sector and adverse working conditions in schools are making teaching an undesirable profession. These are all important considerations, but they do not get at the level of an essential nuance: The factors that lead to attrition are diverse, so treating teachers as a monolith doesn’t help in crafting solutions to the real staffing challenges that some schools face. But a growing body of research can shed some light on these issues.

It is important to begin by recognizing two fundamental points.

First, there is no national teacher labor market. Each state adopts rules for pay, licensure, tenure, pension and training requirements. Consequently, states are not in lockstep with one another when it comes to changes over time in graduation from teacher education programs. This is illustrated in recent research on education majors, broken down by state. For instance, while most states witnessed declines from 2011 to 2015 in the number of teacher candidates who graduated, a few, like Massachusetts, North Dakota and Virginia, saw increases. But, moreover, it is challenging to get an accurate national picture of the early teacher pipeline because the two main federal sources for teacher education data, Title II and the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), are incomplete and often contradictory. For instance, Oregon appears to have had a decrease in teacher education graduates according to Title II reports. By contrast, data from IPEDS shows the state to have a large (50 percent) increase in completers.

Second, there is not an overall teacher shortage. Nationally, each year, there are tens of thousands more people prepared to teach than there are available teaching positions. There are, however, more specific challenges to staffing classrooms in particular schools and subjects. While some schools have applicants lined up when a position becomes available, others, typically those serving economically disadvantaged students, have far fewer applicants. And, more generally, schools tend to struggle to find teachers with special education or STEM training.

These points are all illustrated by recent using data from Washington state. For instance, in 2015, colleagues and I explored interstate mobility and discovered that a very small number of teachers with experience teaching in Oregon end up in the teacher workforce in Washington (and vice versa). Even among school districts near the state border, almost three times as many teachers make a within-state move of 75 or more miles than make a cross-state move. This points to the need to rethink licensure reciprocity to make sure educators don’t drop out of the teacher labor market because they view getting licensed in a new state as too onerous when they move.

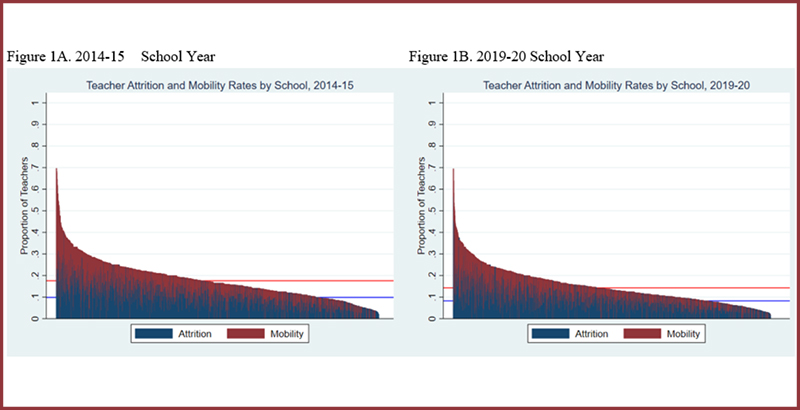

More recently, using 35 years of data on teacher mobility and attrition, we found persistent differences in the attrition of teachers in high-poverty versus low-poverty schools (using free and reduced-price meals as an indicator of poverty). The disparity is about 4 percentage points. That may not sound like a lot, but it is far larger than the year-to-year differences in statewide attrition, which generally varies by less than a percentage point from one year to the next.

Importantly, the difference in attrition in high- and low-poverty schools means that high-poverty schools in Washington need to replace about 400 more teachers every year than do low-poverty schools.

Finally, just-released research tracking a decade’s worth of Washington state teacher candidates into the labor market found that the number of potential teachers — individuals credentialed but not employed in public school teaching positions — is quite different depending on the area of training. More specifically, the number of individuals trained as elementary teachers exceeded the number of leaving the profession by about 25 percent. But there were fewer teacher candidates trained as STEM educators than positions that needed filling in schools. How do we encourage a deeper STEM bench? One clear signal would be to increase these teachers’ starting salaries.

What all this suggests is a need to go deeper in the public discourse about teaching and the pursuit of a career in education. If the message is that people en masse are turning away from teaching as a profession, it might push policymakers toward generic solutions to the problem, such as across-the-board pay increases. While teacher salaries are certainly an issue, it is not clear that general raises do much to address the real challenges of drawing individuals with specific talents into teaching and getting educators to take jobs in particular types of schools.

The pandemic certainly raises concerns about teacher shortages, and more stories will be written, told and amplified to influence the public and policymakers. But the truth is we know a lot more about the teacher labor market than what anecdotes and national data tell us. It’s my hope that we will use that information to have a more nuanced conversation about teacher staffing and come up with more effective solutions to the real problems that do exist.

Dan Goldhaber is director of the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institutes for Research and of the Center for Education Data & Research at the University of Washington.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)