Amid Pandemic Downturn, New Research Shows Great Recession Hurt Student Test Scores, Widened Achievement Gaps & Reduced College Attendance

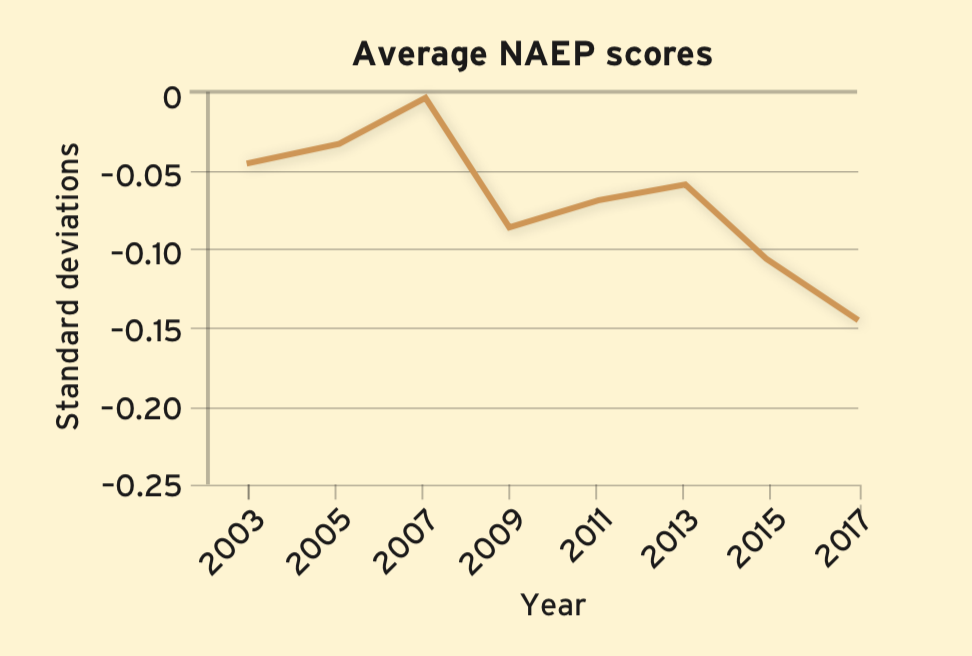

Despite a boost from federal stimulus funds, drops in state funding for education during the Great Recession effectively ended a 50-year upward trend in national reading and math scores, according to a paper appearing Tuesday in the journal Education Next.

A $1,000 cut in per-pupil spending also led to a decline in the college enrollment rate among “students on track to become first-time college freshmen,” especially at two-year schools, according to the analysis, led by C. Kirabo Jackson, a labor economist at Northwestern University.

That decline in per-student spending also correlated with wider test score gaps between poor and non-poor students and between Black and white students, the authors wrote, noting, as others have, that the effects of the Great Recession were long-lasting.

With the nation now in another recession, they stress that if states reduce spending for schools, they “may wish to prioritize restoring education budgets as soon as possible after the recovery.”

Nevada and Georgia are among states that have already seen significant cuts to education, and in Michigan, officials warn that school cuts might be inevitable if Congress doesn’t include more funds for states and localities in the next recovery package.

The Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions — or HEROES — Act, passed by the Democratic-controlled House in May, includes almost $900 billion in flexible funding for states and local governments to offset losses in state revenue and keep frontline workers, including teachers, employed.

State “budgets are in the tank,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-New York, said on the Senate floor last month when the Republicans introduced their package. The HEALS Act, which stands for Health, Economic Assistance, Liability Protection, and Schools, doesn’t include new funds for states and cities. So far, there’s been little movement toward a compromise between the Democrats’ $3.5 trillion plan and the Republicans’ $1 trillion plan.

Michael Griffith, a school funding expert at the Learning Policy Institute, wrote that although current estimates put education cuts in the 10 to 20 percent range, reductions could be larger in the 2021-22 school year “when the income tax effects will be felt more fully.”

Crowding out school funding

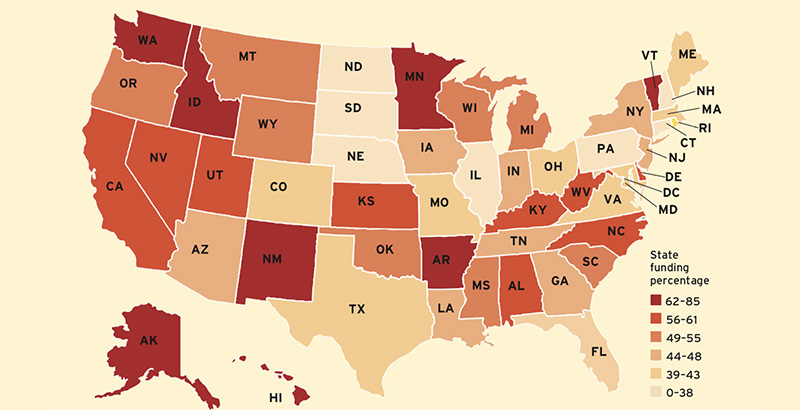

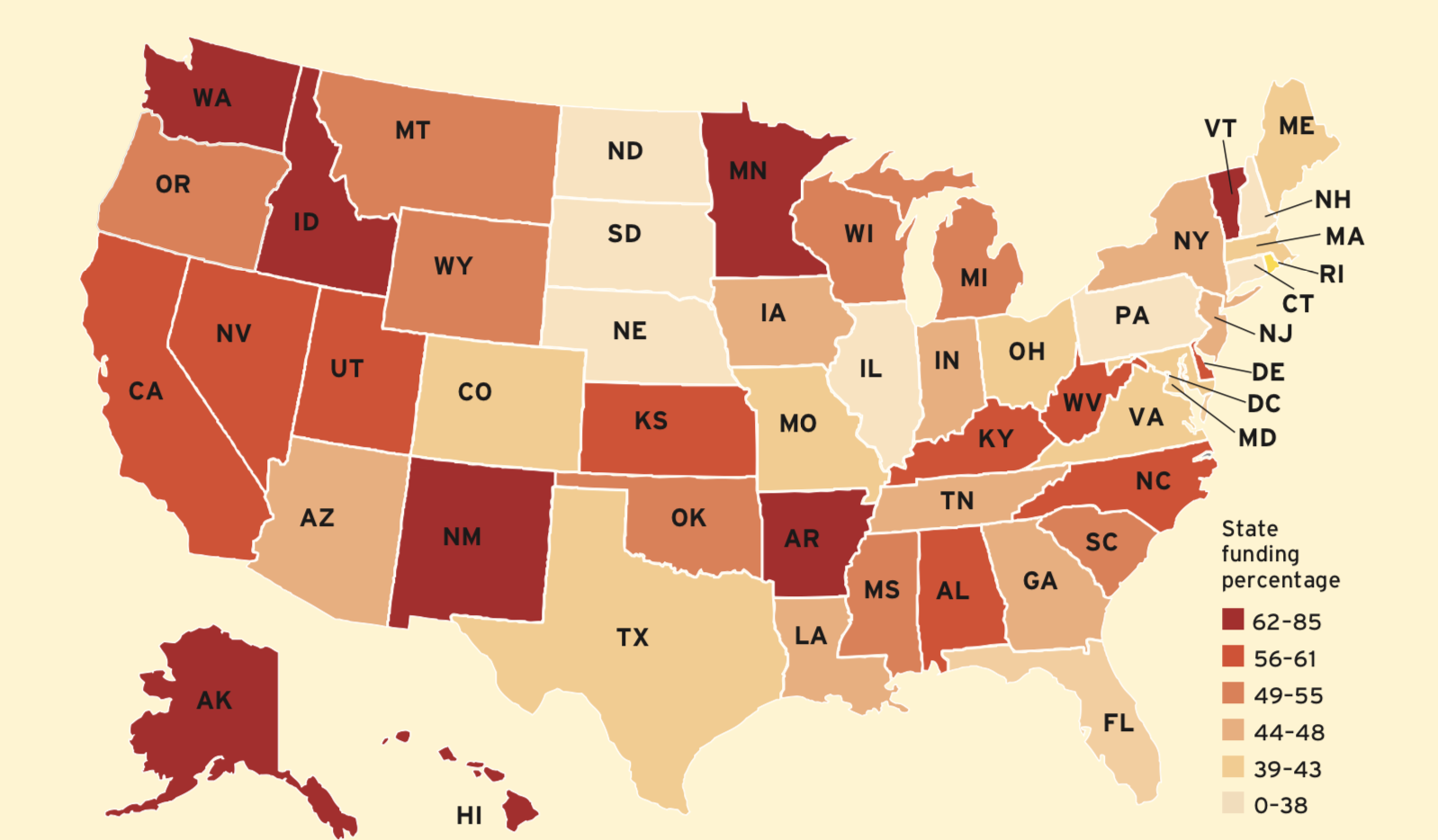

Jackson and his co-authors note that when a larger proportion of the education budget comes from the states, policymakers may “crowd out” funding for schools when they see declines in revenue so they can cover expenses such as Medicaid and unemployment insurance. State budgets also depend on sales and income taxes, which can take a more immediate hit during a recession. But when a greater proportion of the education budget comes from local property taxes, funding is more stable.

Overall, they write that the percentage of state budgets spent on education fell from about 27 percent before the Great Recession to an average of 23 percent in 2009 and remained at that level until 2015. A separate analysis, from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, showed that even through 2017, K-12 funding was still 10 percent lower than pre-recession levels in seven states.

Jackson’s paper notes that the cuts to education budgets resulted in fewer teachers, instructional aides and library staff — but gutted the number of guidance counselors. Class sizes for teachers increased by 0.3 students, but counselors’ caseloads increased by an average of 80 students.

Jackson points to declines in reading and math scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress to illustrate the impact of the Great Recession on student learning. But his paper comes at a moment when the National Center for Education Statistics has indicated that it might not even be able to conduct technically reliable assessments in reading and math next year because so many students will still likely be learning from home.

That would make it difficult to gather data on how the pandemic and school closures have affected student achievement and the gaps between student groups. On Friday, the National Assessment Governing Board, which sets policy for the testing program, approved a resolution to proceed with plans for the tests, despite warnings from school officials and public health experts that there might still not be enough students present in school this spring to collect accurate data.

‘The chaos that ensued’

Other lessons from the Great Recession for schools include impacts on housing and student mobility. In 2017, Kfir Mordechay, an education professor at Pepperdine University in Los Angeles, published a paper showing increases in school transfers among high school students in San Bernardino County, California — a region where foreclosure and unemployment rates soared and were slow to recover.

He found that student mobility rates especially increased among Black students. And in interviews, school leaders told him that Latino families often doubled up with relatives, while Black families were more likely to move far enough to require a school transfer.

“It gave me insight into some of the chaos that ensued in the results of a recession,” Mordechay said in a recent interview, noting the negative effects of mobility on student achievement. “It’s one thing to have a student move in the summer and start school fresh in the fall. But it’s another thing when students have to move in the middle of the school year.”

Although governments have issued temporary moratoriums on evictions since the pandemic hit the U.S., many of those bans have now expired.

Mike Magee, CEO of Chiefs for Change, said he expects student turnover rates to be high. “The levels of unemployment are bound to increase the levels of mobility,” he said.

Another recession-related indicator districts should watch, Mordechay said, is the “rent burden” families feel when they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. Between 2001 and 2015, the rate of rent-burdened families increased by about 19 percent, research shows. And the rate of those spending at least half of their income on rent increased by 42 percent.

A separate study found that during the Great Recession, there was a 17 percent increase nationally in the number of very low-income families competing for affordable rental units.

“The economy is a very fragile thing,” Mordechay said. “You mess with one thing in the system and it affects everything else. There are millions of families that don’t have a lot of margin of error.”

Regarding students’ pathways toward college, the authors of the Education Next paper wrote that the spending cuts most affected students entering two-year schools — a 5.9 percent drop in first-time enrollment, compared with 1.2 percent at four-year schools. They added that the spending cuts possibly undermined “some students’ momentum during a critical moment of transition from K-12 to higher education.” And while the team didn’t test whether cuts in school counseling services contributed to the decline in enrollment rates, Jackson said that “that would be consistent with our results.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)