Aldeman: Teacher Pensions Took a Beating in the Great Recession and Passed the Costs on to New Employees. It’s Probably Going to Happen Again

With stock markets plummeting around the world, pension plans covering teachers, police officers and other public servants lost an estimated $419 billion in the first quarter of the year.

Pension plan managers say their funds are meant to be patient, long-term investors and that if anybody should be prepared to weather an economic meltdown, it should be public-sector pension plans.

That is mostly true for current retirees. It’s possible that some states will halt their planned cost-of-living increases, but otherwise retirees can be comfortable knowing their pension checks will keep coming, just as promised.

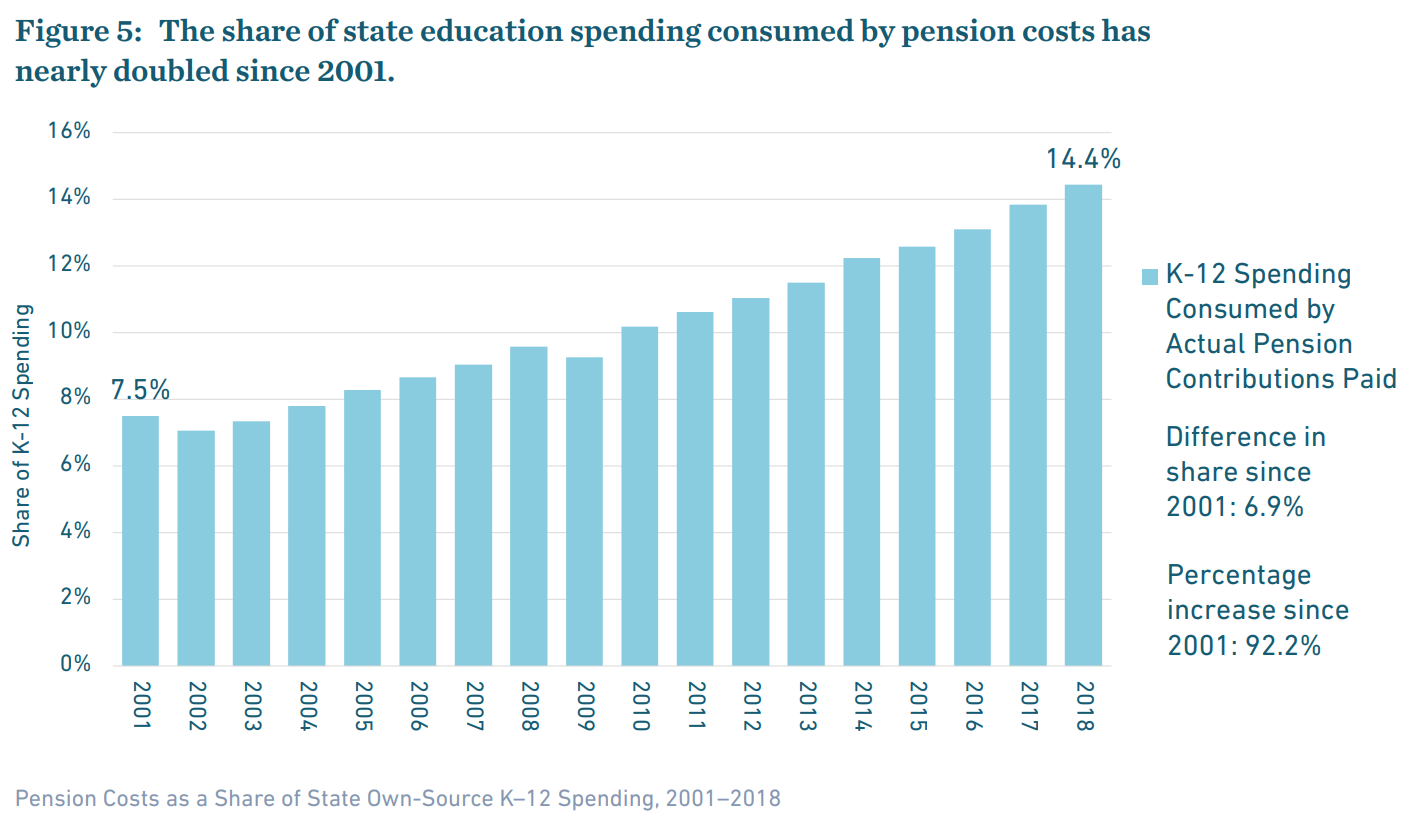

And yet, if pension plans continue operating as normal, they will weather this economic storm just like they did the last one — by passing the costs on to the next generation of workers. For example, a recent analysis from Equable Institute found that the share of state education funding going toward pension costs nearly doubled from 2001 to 2018.

Pension plans rely on assumptions about how much they’ll earn on their investments in order to calculate how much they need to save today. The typical teacher pension plan assumes it will earn a nice, smooth 7.25 percent return year after year after year.

But the real world doesn’t produce nice, smooth, constant returns like that — and this volatility matters a great deal. Even if a pension plan eventually hits its investment return target over the long term, it could still fall short of having enough money to pay for its promised benefits. For example, pension plans have averaged returns of 7 to 8 percent over the past 25 or 30 years, even while their funding status has deteriorated substantially.

So what will the current market downturn mean for teachers? It’s still too early to know for sure, but it’s instructive to look back at the last recession. Let’s use the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) as an example. It’s the largest teacher retirement plan, serving nearly 650,000 active members and 300,000 retirees.

In 2008, CalSTRS assumed it would earn 8 percent on its investments. Instead, it lost 4 percent. In 2009, CalSTRS again assumed it would earn 8 percent. Instead, it suffered a 25 percent decline. After a couple of roller-coaster years, CalSTRS assets declined a total of about 3 percent from 2007 to 2012.

That may not sound too bad, but CalSTRS’s obligations to pay future benefits kept right on growing. From 2007 to 2012, those liabilities grew 29 percent, or about $48 billion.

Between declining assets and rising liabilities, CalSTRS went from being 89 percent funded in 2007 to 67 percent funded in 2012. Its unfunded liabilities — the gap between what it had saved and what it owed to current and future retirees — grew from $19 billion to $71 billion.

Rather than seizing the opportunity to consider alternative models, California legislators hunkered down with a number of small changes. Like most states, California made its pension benefits worse by creating a new, less generous tier of pension benefits that applied only to new hires. For those workers only, California raised the retirement age by two years.

The state also increased contribution rates required of teachers themselves, as well as state and district budgets. In legislation passed in 2014, the state scheduled CalSTRS contribution rates to slowly ramp up from a total of 18.3 percent in 2014 to 35.3 percent in 2020-21. (Districts got a brief reprieve from that upward march last year, when budgets were flush.)

Even this has not been enough. In fact, despite the increases, California and its school districts have still not made sufficient contributions in any year going back to 2001. On average over this period, they’ve put in about one-third less than what their actuaries told them they needed to contribute. In simple terms, it’s as if CalSTRS has been making its minimum credit card payments even as its interest owed keeps rising.

As a result, CalSTRS is not prepared for the coming recession. Its unfunded liability had risen to $107 billion as of last April, and it’s surely much higher today. As in the last recession, costs are likely to trickle down to teachers through even higher contribution rates — further cuts in their take-home pay — not to mention frozen salary schedules and less money available for all other education priorities.

A couple of years ago, I warned about the “Pension Pac-Man,”an all-consuming creature that is devouring school budgets. While no one knew then about the prospect of COVID-19, the pension problem that policymakers have been trying to hide from is about to cause a world of hurt to state and local budgets. This time around, let’s hope they make better choices.

Chad Aldeman is a senior associate partner at Bellwether Education Partners and the editor of TeacherPensions.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)