Aldeman: How La.’s Teacher Pension System Can Be Both Crushingly Expensive and Not Very Good for Educators

In a new report released last week, my co-author Paulina Diaz Aguirre and I showed that Louisiana’s teacher pension system is one of the most expensive — and also one of the worst — retirement plans in the country.

How can a retirement plan be both expensive for employers and meager for workers? That seeming riddle is the key to understanding how the teacher pension plan works in Louisiana, and also how similar teacher retirement plans are working in most other states across the country.

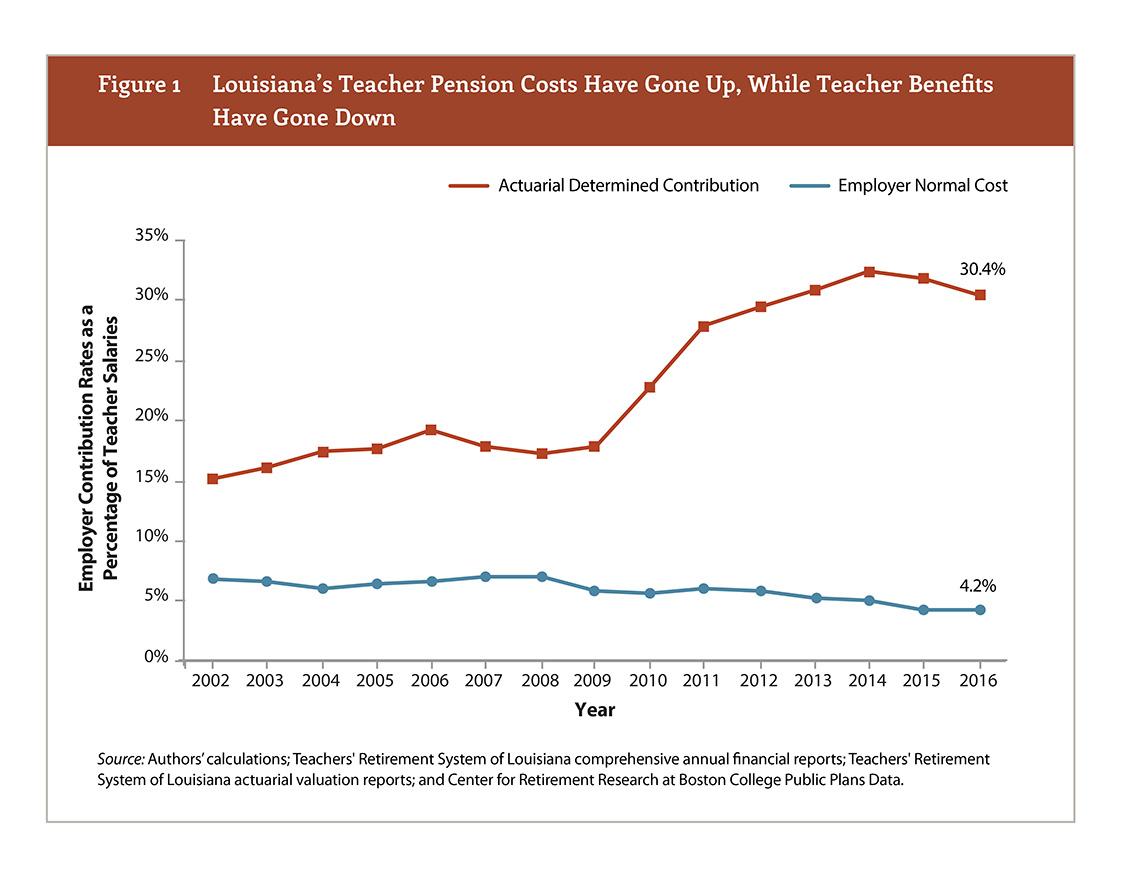

Consider the graph below, which appears as Figure 1 in our paper. The red line shows the state’s “actuarially determined contribution,” that is, how much the state’s actuaries say districts need to contribute. That figure includes the actuaries’ estimate for how much the state’s retirement benefits are worth and the amount needed to pay down unfunded liabilities that have been racked up over years of over-promising and under-saving.

In Louisiana, that unfunded liability is over $11 billion, and it’s led to years of dramatically rising pension costs. As a result, districts contribute more than 30 percent of each teacher’s salary annually toward the state’s pension plan. The vast majority of this contribution goes toward paying down debt, not toward benefits for current workers.

For most workers, rising employer contributions would mean better retirement benefits. That is not the case for Louisiana’s teachers, or for other teachers nationwide. The blue line in the graph below represents Louisiana’s estimates for the value of an average teacher’s retirement benefit. Louisiana, like most other states, has been cutting retirement benefits over time, and consequently its “employer normal cost” of benefits keeps falling as new workers enter the workforce with worse retirement benefits than their predecessors had.

In a response to our piece, the head of the Teachers’ Retirement System of Louisiana, Dana Vicknair, took umbrage at our characterization. She noted, without irony, that state legislators “have taken responsible steps since the late 1980s to contain retirement costs.” Vicknair is right that the state has “contained” retirement costs by cutting benefits for teachers, but the total costs to the system have soared dramatically.

As a result, Louisiana’s school districts are pouring money into the pension system but teachers aren’t getting much out of it. Going back to the graph, the state pension system estimates the average value of teachers’ retirement benefits to be worth only about 4 percent of their salary. This is comparable to a 4 percent employer match on a 401(k) plan, which might sound OK except for two distinctions that put Louisiana teachers in even worse shape.

One, teachers aren’t actually guaranteed that 4 percent like they would be in a 401(k) plan. Instead, Louisiana’s pension system is a defined benefit plan, meaning it guarantees workers a certain amount of payments in retirement depending on their salary and length of service. Some teachers do much better under this arrangement than others, and the 4 percent represents an average spread out across all of them; many get much less.

In fact, nearly half of all Louisiana teachers fail to stay long enough to qualify for any retirement benefits at all, and the plan uses a back-loaded formula that disproportionately rewards the small fraction of teachers who remain on the job for more than 25 years. Just 1 percent of teachers will stay in the classroom long enough to earn the maximum retirement benefit.

And two, unlike all workers in the private sector, Louisiana has chosen not to offer its teachers Social Security coverage. Due to a historical quirk, state and local governments were given the option over whether they wanted to enroll their workers in Social Security, and Louisiana is one of 15 states that do not cover all their teachers. That decision leaves teachers particularly vulnerable to a bad retirement plan like the one the state is currently offering. Once you factor in Louisiana teachers’ lack of Social Security, their retirement coverage is one of the worst in the country.

Luckily, Louisiana has better options. There’s not much juice to squeeze out of the current system — the debt has to be paid regardless, and a 4 percent retirement contribution doesn’t leave much with which to work. But there are still cost-neutral ways, like allowing teachers to join the same retirement system currently offered to the state’s higher-education employees, that would give all teachers fair, portable retirement benefits. Perhaps even more important, those alternatives would prevent the state from accumulating more debt in the future.

As we note in our report, Louisiana school districts have been cutting their expenditures on instructional programs, textbooks and other school supplies, and special education services, at least partially due to rising pension costs. Without reform, those trends are likely to continue.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)