After 7 School Integration Strikes, NYC Students Get Rare Public Meeting With Ed Department Officials, Asking ‘How Much Longer Will We Have to Wait?’

Updated

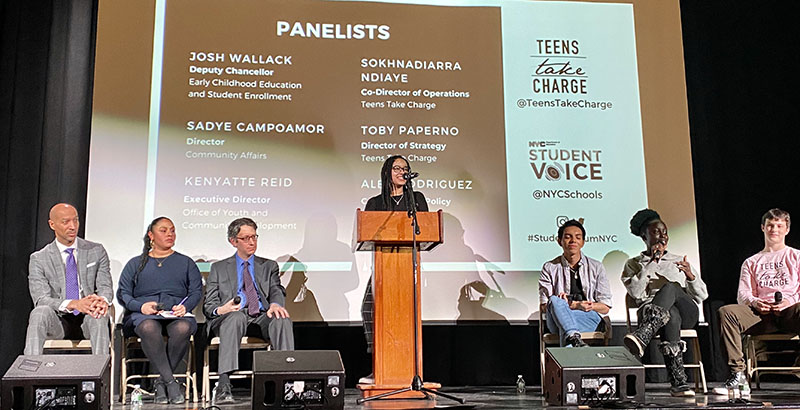

After weeks of Monday strikes demanding school desegregation, several hundred New York City teens turned out to quiz education department officials directly about what is being done to make schools more integrated and equitable.

“Segregation is a citywide issue which requires a citywide solution,” student panelist Toby Paperno told three Department of Education officials in front of more than 300 attendees at the Bayard Rustin Educational Complex in Chelsea.

Thursday night’s forum was the first time student advocacy group Teens Take Charge had hosted an event specifically for students to ask Department of Education officials about school diversity, integration and equal resources. New York City is the largest and one of the most segregated school districts in the country, with only 28 percent of schools in the city considered “diverse.” More than 1,300 students have turned out for seven strikes demanding immediate action on integration since mid-November, though those near-weekly strikes are on pause as of Monday.

Three Teens Take Charge leaders, including Paperno, shared the stage with Kenyatte Reid, the DOE’s executive director of the Office of Safety and Youth Development; Sayde Campoamor, director of community affairs; and Josh Wallack, deputy chancellor for early childhood education and student enrollment. The forum was planned in collaboration with the DOE’s Student Voice Team.

Students sharply questioned the DOE about its progress on what they consider integral steps toward desegregation: eliminating competitive admissions screens at middle and high schools, ensuring all schools have equal resources, and fostering inclusive school climates. Throughout the forum, both students and DOE officials agreed that integrating schools is a top priority. There was considerable discord, however, on the extent of community engagement and time needed to usher in widespread change.

Officials said they’re taking “bites at the apple,” notably by supporting integration efforts at the local level, such as in Brooklyn’s District 15. But for systemwide desegregation to be successful, they stressed that there needs to be robust community engagement and buy-in. Many integration proposals thus far have elicited apprehension and vitriol from predominantly white and Asian parents.

“We believe that we will make more change and make it stick if we hear from voices all over the city, and try to explain and make a case that integrated schools are stronger schools,” Wallack said.

For many students, however, the fact that it’s been 65 years since Brown v. Board of Education — the landmark Supreme Court ruling that declared separate but equal schools unconstitutional — is a sign that community engagement can only go so far.

“There are some things where, yes, it’s important to have conversations,” said Sokhnadiarra Ndiaye, one of the Teens Take Charge panelists. “But at what point in the conversation do we pause and say, ‘You know what? It’s about time we did away with the system.’”

Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza, who have taken heat from student activists for lagging systemwide integration efforts, were not asked to attend.

Inequitable resources

One key point of discussion at Thursday’s forum was the pervasive inequality across schools when it comes to sports programming and resources like PTA funding.

Paperno attends Beacon High School, a selective college-preparatory school in Manhattan’s Hell’s Kitchen where half of the students are white. The school has more than 25 sports teams. One of those, the ultimate frisbee team, “has really helped me grow a lot as a student,” he said.

He turned to his peer Ndiaye, also on stage, who attends a school with mostly black and brown students. “Sokhnadiarra’s school, [Brooklyn College Academy], has next to none. They have two sports teams. That difference is insane.”

Paperno asked the DOE: What is your plan for adjusting the inequities in sports at schools?

Campoamor, the director of community affairs, pointed to a shared teams pilot program announced last spring across 23 high schools, where students from neighboring schools come together to play as one team. The intent is “to only expand,” she said, “because we do believe that access to sports in an equitable way is critical for our young people.”

The state owes at least $1.1 billion in funding to city schools, she added, which would help fill resource gaps.

“We think the [state funding] formula itself needs to be amended, so we’re working with our partners in Albany to fully fund our schools,” she said. New York City spends an average of $28,808 per student — higher than most other large, urban districts — though the state’s share of the city’s school budget has been dropping.

Another student, Mika Shiffman from Millennium Brooklyn High School, asked if the DOE was planning to change the way PTAs can raise money “in order for all students to receive an equitable and fair education.” PTA funding can hinge on zip code; a wealthy Upper West Side school saw $2.1 million in PTA funding last year, for example, compared with some schools in higher-poverty areas reporting less than $5.

Her question prompted the forum’s moderator, Teens Take Charge leader Tiffani Torres, to ask the audience how much their own schools raise. Beacon High School, Paperno’s school, raises more than $500,000 annually, he said. (Chalkbeat’s data tool puts it at $685,767.)

“Less than that!” one student shouted.

“$1,200,” another called out.

“$500.”

Education department officials didn’t expound on changing PTA funding protocol, but Campoamor acknowledged that “we need to think of resources more expansively, which includes PTA funding.”

Targeting admissions screens

Top of mind for students was also admissions screens.

More than 20 percent of New York City’s middle and high schools have admissions screens, meaning they consider students based on factors such as their grades, state exam scores, attendance, essays, interviews and zip codes. Research shows that schools with some type of admissions screen — excluding those that are designed for English learners — are more likely to have student bodies unrepresentative of their neighborhood populations.

Yet “[Mayor] de Blasio has not eliminated or even reduced the use of these discriminatory screens,” moderator Torres said. “Why not?”

Wallack acknowledged that the DOE isn’t “remotely close to doing enough … but we’re working on it.” He noted how the district already ended “limited unscreened” high schools, which had no academic requirements but gave preference to families who had the time to attend open houses. Wallack added that the DOE is also “particularly targeting schools in underserved neighborhoods with a range of programs,” including AP for All, 3K and Pre-K for All, Computer Science for All and College Access for All.

The DOE is continuing to review the latest School Diversity Advisory Group recommendations put forth in August as well, he said. Those recommendations included dismantling gifted and talented programs.

Torres asked pointedly whether DOE officials “believe that screens are discriminatory.” Another student requested an answer, “honestly,” on whether screens could be removed from all schools within the next three years.

Wallack said the department couldn’t commit to a timeline. And on the discriminatory nature of screens — it could be situational.

“We see some screens that clearly have a disproportionate result, and those we’re looking at really intensely,” he said. “There are others that screen for things like language or interest or audition, that may be a benefit to the system … we’re trying to take a nuanced view and listen to you and other stakeholders to get that balance right.”

On the topic of the SHSAT, the controversial exam that determines whether students get into eight of the city’s storied specialized high schools, Wallack reiterated prior district sentiment that “the admissions test should be scrapped.”

A bill to eliminate that exam failed to gain momentum in the state Assembly last year. State law dictates admissions at three of the eight schools.

Improving school climate

Many in attendance also wanted to know what’s being done to make schools safer and more inclusive for students of color.

“Integrated classrooms are not just about giving the black and brown kids what the white kids have. It’s about creating environments that foster learning for all students and decrease social anxiety,” said Alexander Rodriguez, a Teens Take Charge panelist.

A few students cited concerns, for example, with the use of metal detectors in schools, which disproportionately end up targeting black and brown students. Zoe Simpson, from the Urban Assembly School for Law and Justice, also asked what the DOE is doing to address the power imbalance that arises when staff don’t accurately reflect the student body.

“The faculty who look like me and who I can identify with are the correctional officers. They’re the people that I go to when my teachers feel disrespected in the classroom or they feel their white fragility has been challenged,” she said.

Although DOE officials didn’t offer an explicit plan or timeline to further diversify its workforce, Campoamor, the director of community affairs, acknowledged, “Representation is a really big deal in New York City right now. We don’t think that our teachers are as representative at all of the students, and we realize that that has an impact.”

About 42 percent of city teachers are educators of color, serving a student body that is about 80 percent minority.

Reid, the executive director of the Office of Safety and Youth Development, said the Office of Equity and Access has to train every educator over the next three years on implicit bias and culturally responsive education, or teaching that embraces curricula relevant to marginalized students’ experiences.

DeKaila Wilson, director of decriminalization with student group IntegrateNYC, asked about the scope of the district’s investment in restorative justice practices, which focus on how to de-escalate conflicts and rebuild relationships with students who act out, rather than taking punitive action. Reid said the DOE is currently supporting 502 schools citywide but hopes to expand trainings “to all middle and high schools.”

“All schools are open to do [trainings],” he said, adding that schools that send five staff members can receive four days of on-site coaching. Reid directed attendees to nycdoerestorativepractices.org, which has videos explaining what restorative justice is, along with the email RespectforAll@schools.nyc.gov for more information.

The nearly two-hour forum ended with students still lined up at the microphone with questions. Although DOE officials declined Teens Take Charge’s request to answer remaining questions directly with students on Twitter, they said they will answer emails sent to the district’s new student voice manager at studentvoice@schools.nyc.gov.

One of the last questions to the panelists was what they’d learned that night. For Reid, it was the depth of students’ frustration.

“What I’m learning today is that we have to have an expedited approach to integrating schools,” he said. The room erupted.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)