A School Budget Showdown in California: Why the State and County Have Warned Los Angeles Unified to Get Its Financial House in Order — or They’re Taking Over

This article was produced in partnership with LA School Report.

The Los Angeles Unified School District board was jolted last month when a top county official showed up unannounced to say, You’re spending more money than you make and the savings you’ve been living off of are about to run out.

It got worse two weeks ago, when she came back and brought a top state official with the same message.

“Yes, my presence is indicative that this is serious,” said Nick Schweizer, deputy superintendent of public instruction for the California Department of Education, who joined Candi Clark, chief financial officer of the Los Angeles County Office of Education, at the Sept. 11 board meeting. The two warned L.A. school board members that time is running out for them to get their house in order — or they will lose control over it and the state will eventually take over.

First step to avoiding a takeover: Cut what you spend

L.A. Unified has to act now, and it has three choices, the officials said: Make more money, cut spending, or do both.

One choice L.A. Unified has not made is to cut jobs. “It is our choice not to reduce our workforce in the current year,” school board president Mónica García said.

“We are looking at the impact of those choices, and you’re right, it is your decision whether or not you choose to reduce over here or reduce over there. But when we look at a budget and we see, for example, your fund balance is doing this, is going straight down, that tells us that there needs to be some additional shift,” Clark said.

“It’s very clear that you are living off the reserves. That’s not wise, that’s not fiscal prudence … that doesn’t get us to the path of fiscal solvency. And so, while the choice may be to keep an expenditure over here, the expectation is that the board is going to look at other expenses and make some adjustments either up or down, or revenue enhancements, but it can’t be simply looking at the fund balance and continuing to see it dwindle down below the requirement.”

Dr Candi Clark, CFO of @lacoeinfo, sent a sobering message to the @LASchools Bd today:

The window is closing for LA Unified to address our fiscal situation. #LAUSD cannot continue to drain its reserves. We must increase revenues, decrease spending, or do both.

— Nick Melvoin (@nickmelvoin) September 11, 2018

Clark, who is legally required to act if a school district will run out of money within three years, has given L.A. Unified until Oct. 8 to adjust its budget, including detailing exactly how the district expects to make the $73 million in cuts it has vowed to carve out of the next two years’ budgets.

If the county isn’t satisfied, it will “disapprove” the district’s budget. (Last week, Clark gave the $7.5 billion budget a “conditional” approval.) The next step is assigning a financial expert to assist the district, then imposing a fiscal adviser, which would be unprecedented for L.A. Unified and would strip both the superintendent and the school board of power. Clark outlined that step when she showed up unexpectedly at last month’s school board meeting.

The final step would be a state takeover, which happened in neighboring Compton in 1993 and in Inglewood in 2012. And as Schweizer warned last week, “LAUSD is in a worse condition than many others.”

One board member sees staffing cuts coming as soon as next year. “Next year, we’re going to have to cut people … in massive numbers,” Richard Vladovic said last week. “If I were the superintendent, I’d be freaking out about this report.”

“Next year we’re going to have to cut people … in massive numbers. … If I were the superintendent, I’d be freaking out about this report.” @richardvladovic @LASchools pic.twitter.com/Jl4JrrQbib

— Laura Greanias (@LauraGreanias) September 11, 2018

Next step to avoiding a takeover: Make more money

School districts make money when kids come to school — and L.A. Unified is losing students at a clip of about 16,000 each year. Plus, the district has a stubborn attendance problem with the kids who do enroll, though it is working to fix that.

So, to get more money, school districts need to:

—Ask for a raise (L.A. Unified is actively lobbying the state and federal governments for more money, but no one predicts the district will get it);

—Ask for handouts (like philanthropy, and L.A. Unified does benefit from some and is working to get more);

—Persuade California voters to raise taxes.

That last option is what the district endorsed last week.

In a “symbolic” move, the board voted unanimously to back the California Schools and Local Communities Funding Act on the November 2020 ballot, which will ask California voters to impose a special tax on commercial property owners.

If voters approve, the tax would raise more than $11 billion for schools and local communities throughout the state, including $1.4 billion for Los Angeles County schools, according to the Schools and Communities First coalition, a statewide alliance of 280 community organizations, labor unions, business leaders, philanthropic foundations, and elected officials.

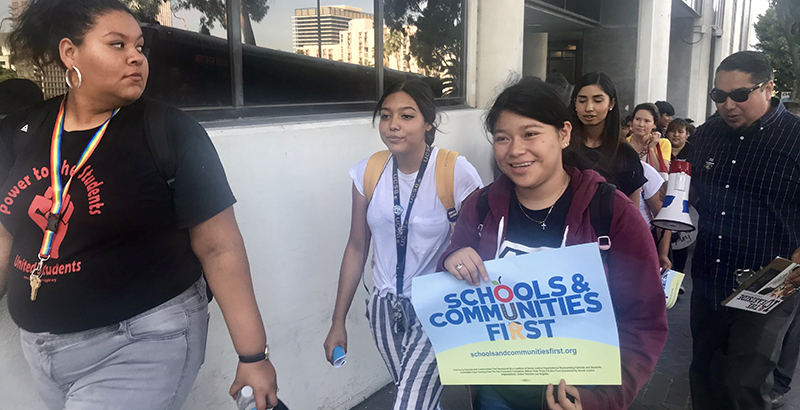

“The measure has been approved to be in the ballot, as we submitted over 870,000 signatures last month in order to qualify the initiative, so today’s vote by the board is symbolic, but their endorsement represents a significant milestone,” Kevin Perez Allen, a coalition spokesperson, said last week outside L.A. Unified’s boardroom.

Dozens of coalition members rallied outside the boardroom during the meeting, calling on board members to throw their support behind the measure. One of them was student Chelsea Rosales, who recently graduated from Woodrow Wilson High School in El Sereno. “For someone like me who comes from a low-income community school, I know what it’s like not to have sufficient resources, not having that support on campus. A lot of students like me need that money back in our schools,” she said while waiting to get inside the boardroom.

“California currently ranks 41st in per-pupil spending, putting a severe strain on students, families, and teachers of our K-12 schools and community colleges,” García, a co-author of the resolution to support the ballot measure, said in a statement after she won her colleagues’ support. “This initiative will help to boost that funding, especially in the poorest and most needy school districts. It will allow us to have smaller class sizes and restore funding for programs that have been cut in the sciences, arts, and music.”

However, by the time a vote happens in 2020, L.A. Unified’s savings are expected to be gone — and by law, the county will be forced to act before then.

What does this mean for the teacher contract talks?

The county and state officials both expressed concern over a threatened teachers strike and that a new contract will be too expensive.

“We are concerned that any salary and benefit increase, whether paid from reserves, assignments, or other one-time resources, could adversely affect the fiscal condition of the District,” Clark wrote in a Sept. 6 letter to García. “These salary increases are expected to exceed the projected state-funded cost-of-living adjustment. Because labor costs make up a large portion of the district’s budget, we are concerned that any salary and benefit increase, whether paid from reserves, assignments, or other one-time resources, could adversely affect the fiscal condition of the district.”

But as a representative of United Teachers Los Angeles told the board last week, “The district’s projected deficits in the third year have never occurred.”

Union vice president Cecily Myart-Cruz told board members that the district’s unrestricted reserve “is now at an astonishing $1.863 billion for the end of the 2017-18 school year, even larger than its previous estimates of $1.7 billion.”

In its response to the district’s financial presentation last week, the union noted that “the state requires only a 1% reserve, yet LAUSD has 26.5% in reserves.”

Press Release: UTLA statement on LAUSD’s $1.86 billion in reserves. LAUSD’s financial officials have a history of pointing to an apocalyptic third year out in their budget documents. https://t.co/CpqqRi1HRr #UTLAStrong #Red4Ed #RedforEd pic.twitter.com/kpPqkBmM7W

— UTLA (@UTLAnow) September 11, 2018

However, as Scott Price, the district’s chief financial officer, showed last week, by 2020-21, that dips to just $1.5 million, or 1.04 percent. The county is required to step in if reserves dip below 1 percent in the third year of a district’s budgeting. And as Clark noted, if L.A. Unified doesn’t cut the $73 million it says it intends to cut — but which it hasn’t shown how it will cut — she will be forced to act.

Remind me, what’s brought L.A. Unified so close to the fiscal cliff?

In short, L.A. Unified is losing thousands of students each year because of lower birth rates, high rents, and parents leaving traditional neighborhood schools for independent charter schools or the suburbs; ballooning pension debt; and a halt to one-time funding that the state has been using to shore up schools.

Clark also pointed to the increasing number of students who are identified as needing special education and the cost of maintaining buildings that are serving fewer and fewer students. Also, the district owes a $35 million penalty to the state for having too many administrators compared to how many teachers it has, though the district is trying to get that waived.

Clark wrote, “We emphasize the need for the board to recognize the long-term impact of the district’s structural deficit spending and are concerned that time-sensitive financial decisions are being postponed indefinitely.”

Esmeralda Fabián Romero contributed to this article.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)