A Reporter’s Burden and a Parent’s Anxiety: The Grief of Uvalde

Journalists can’t fill the void created by repeated mass murders of children. Parents can’t avoid it

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As news ticked in from Uvalde, as the death toll went up…and up again, my first thought was to just be still: If I was really, really quiet this storm would blow over, like so many dark Texas storm clouds that drop not a drop of rain on our thirsty ground.

Maybe, if I could just will it away, it wouldn’t stop and stay, enveloping the tiny, beloved town of Uvalde — where my mother spent summers with her family and my family fuels up for West Texas adventures — in a vise grip of grief, planting itself in the front of our minds so everything feels both fragile and immovably solid.

We see the first faces of victims before the death toll is finalized. Teacher Eva Mireles was the first. Her hiking selfie. Then Xavier Lopez, in his honor roll awards-day outfit. They’ll keep coming. Each one was a whole life, leaving behind a never-whole-again family.

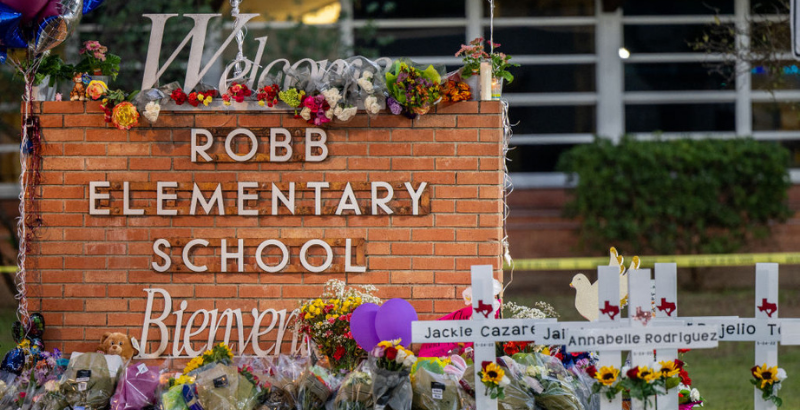

Education reporters will talk about Robb Elementary. Crime reporters will talk about the shooter’s troubling past. Political reporters will chart the politicians going through their post-massacre paces. Religion reporters will desperately try to find something other than thoughts and prayers to report.

Reporters will get to know Uvalde. I know it as the quintessential small town where my mother spent her childhood summers with cousins, getting into scrapes and mischief of every kind; where we stop for groceries as we search for Hill Country swimming holes or take the scenic route to Big Bend, and where two long U.S. highways, U.S. 83 (1,885 miles) and U.S. 90 (1,633) intersect.

Such intersections lend a center-of-the-worldness to a place, and to the people of Uvalde, for the parents of the children there, Uvalde is the center of their world. Robb Elementary School was the center of so many worlds.

We will obsess on these details, because that’s what we in the news do. We get the details.

But our broken hearts will simply be still, unable to feel joy or hope any time soon. At 83 miles away in San Antonio, I don’t know how to think about anything else.

For the town of Uvalde the painful memories will haunt them, another place now synonymous with an act of violence, an unfair commandeering of its identity. For the survivors, a lifetime of nightmares. For the parents, an everlasting grief.

The immersion of school shootings is total: When is it even appropriate to turn your attention then to other stories, other fires, other injustices and solutions? When can you start walking while you chew the gum of grief? Of despair?

When Sandy Hook happened I was barely a reporter. I didn’t have kids. Now I’m a veteran of the education beat, and we have a playbook and tips and seminars for covering these, so common have they become.

Now I have kids. It’s different dropping off your second grader at school so you can go home and write about second graders dying at school.

What do you even tell a child who must leave you in the drop-off line and walk bravely into a place just like the one in the news? We didn’t know what to say on the day of the shooting, afraid to scare our kids, ages five and eight. It was almost bedtime when facts were still being confirmed, and our own shakiness was fresh.

We didn’t want to tell them immediately before drop-off. Maybe we were wrong to wait, but it also turns out there’s no good time to tell your child that 19 other children and two teachers—safe, invincible adults—were shot in school.

We know it’s likely someone will say something at school, before we tell them, and we’re just trying to be ready to respond. Ready to reassure them we’re doing everything we can to keep them safe. We’re reading advice from professionals, so we can be ready to shepherd them through a world we don’t fully understand ourselves. This will be a sad conversation

But right now, even ordinary conversations feel sad, because of how quickly other mothers’ and fathers’ ordinary day became the worst day of their lives. I read those quotes from grieving parents detailing the last thing they said to their children that day, their last memories. They are familiar. They are describing mornings that every parent knows.

Journalists are your eyes on history as it is made, but we are not historians. Or psychologists. We are not trauma surgeons. We don’t know how to do anything but give you the same, somehow inadequate details over and over and over.

We keep trying to do better, and get those details without devouring Uvalde’s 16,000 residents, and the brick and limestone courthouse, the county’s delicious honey. We’ll try to sift through the wreckage and find the stories history needs to have on record.

But the details we can provide aren’t enough, because once you read them—these hallowed names, these heroic stories, these familiar tales of horror—there still are no words for the rest of the story. The news stories will always leave you with a hollow place behind your sternum, because we cannot name the other things a mass shooting takes from us, as a country.

Education reporting is fundamentally hopeful—we are reporting on the only proof we seem to have that our country actually believes the world will continue for another generation.

Education reporting puts you in contact with idealistic teens and adorable preschoolers and this precious demographic of elementary kids ages 8 to 12 —the ones who get lost in “middle grade” books. The ones who understand the significance of “honor roll,” but still don’t have control over “perfect attendance” because their parents have to deliver them to school. But they revel in both awards on award ceremony days like the one interrupted by this tragedy.

And I can tell you all of that, I can bring you all the details of the system that is both failing and delivering our future. But when those details include a massacre of a fourth grade class and two teachers? I cannot put into words that void behind your sternum—somehow hollow and churning and heavy and crackling like fire— the deep wail, the guttural rage, the roar of utter despair.

Because we’re probably going to have to do it again. Don’t get your hopes up for the details of the plan to actually make this a “never again”—the people who could make that plan are speaking at the NRA convention on Friday.

I’ve been lucky enough never to cover a mass shooting in the way that some reporters must, standing on a sidewalk day in and day out.

But I have stood on other sidewalks, covered other tragedies.

My question is always, “What does it look like to be faithful to the truth right now?” If I try to take on the burden of single handedly finding the one detail or quote or expert who will change it all, who will fix everything, failure is inevitable. Such a solution does not exist. I can only ask, “What is of value for people to know? What useful thing can I put in their hands? What is the best outcome we can hope for if people read this story?”

And I have to be ready to be faithful to my kids in that same way. To give them the truth they need and the hope they need.

That’s really hard to do right now, but I don’t think there’s any other way.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)