A Referendum on Race in Board Election for Gwinnett County, One of the Nation’s Largest and Most Stable School Districts

In 2016, Tarece Johnson, a Columbia University-educated diversity expert, met at a McDonalds with Louise Radloff — a school board member in Georgia’s Gwinnett County Public Schools since 1973.

Johnson, who relocated from New York to the Atlanta area in 2005 and opened a private, multilingual school, told Radloff she might run for school board someday.

This year, Johnson not only ran against Radloff — such a longtime fixture in the community that she has a school, health complex, and scholarship named after her — she beat her in the Democratic primary. “I was surprised that she was running again,” Johnson said. “I thought surely she was done.”

With no Republican candidate facing her in the general election, Johnson is poised to take Radloff’s seat in January, making her only the second Black board member in the history of the nation’s twelfth largest school district.

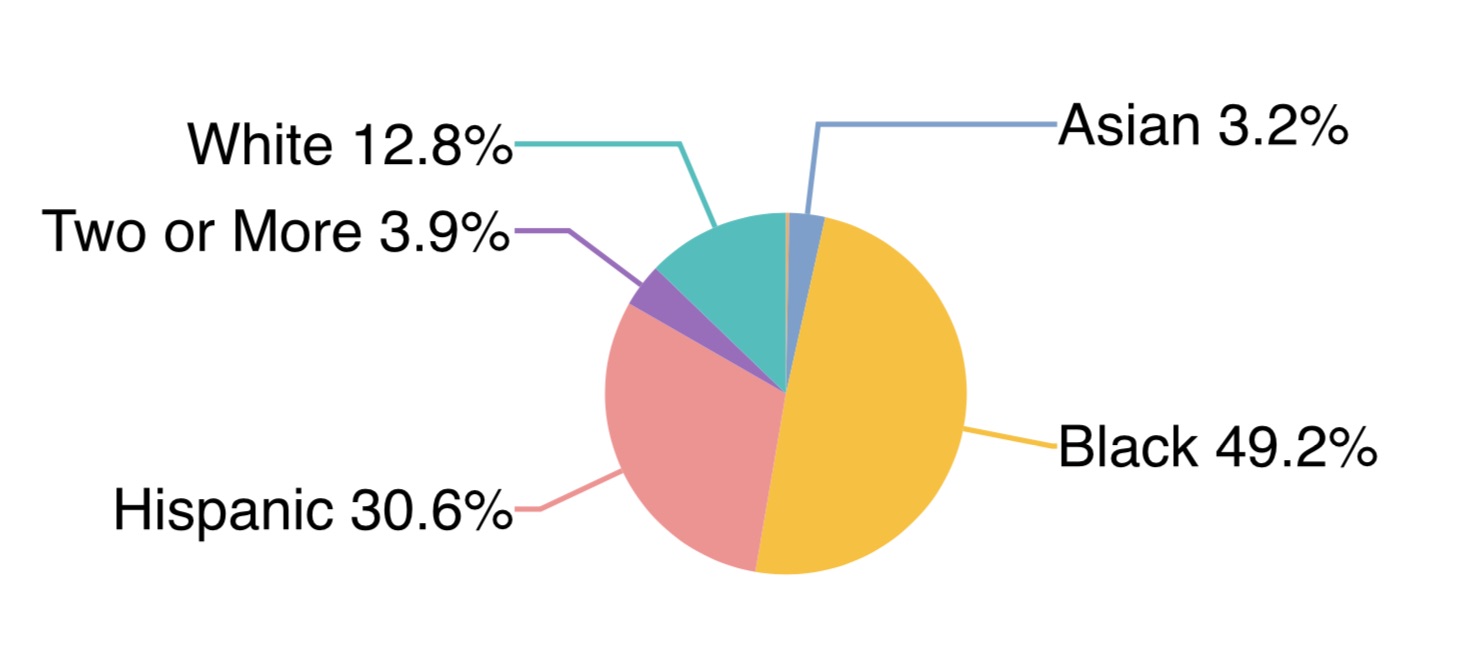

Two other non-white candidates are vying for seats against longtime incumbents in this election — something of a referendum on the changing racial and political demographics in one of the country’s historically most stable and successful school districts.

Karen Watkins, a multiracial mother of two Gwinnett students who works in commercial real estate, is taking on Republican and former teacher Carole Boyce. And Tanisha Banks, a Black special education teacher in one of the district’s alternative schools, is challenging Mary Kay Murphy, who taught English and spent 30 years in higher education fundraising.

Both Boyce and Murphy have served for more than 20 years, with some conservatives characterizing the challengers as a “ticket of radical liberals.”

Banks said she was inspired to run because she thought too many Black and Hispanic students were being assigned to her alternative school. “I just felt that our students were given a disservice, and I felt like the resources weren’t available to help our students that were struggling,” she said.

Everton Blair, a Gwinnett graduate who received national attention two years ago when he became the first Black representative on the five-member board, predicted the seats “are all going to flip.”

“I’ll be the longest serving board member in about three months,” said Blair, who earned degrees from Harvard and Stanford universities, taught in an Atlanta charter school, and returned to the county in 2018 to run for a seat left open by another long-serving member. “People are tired of having a … school board that doesn’t really represent the current needs of our students today.”

‘Golden reputation’

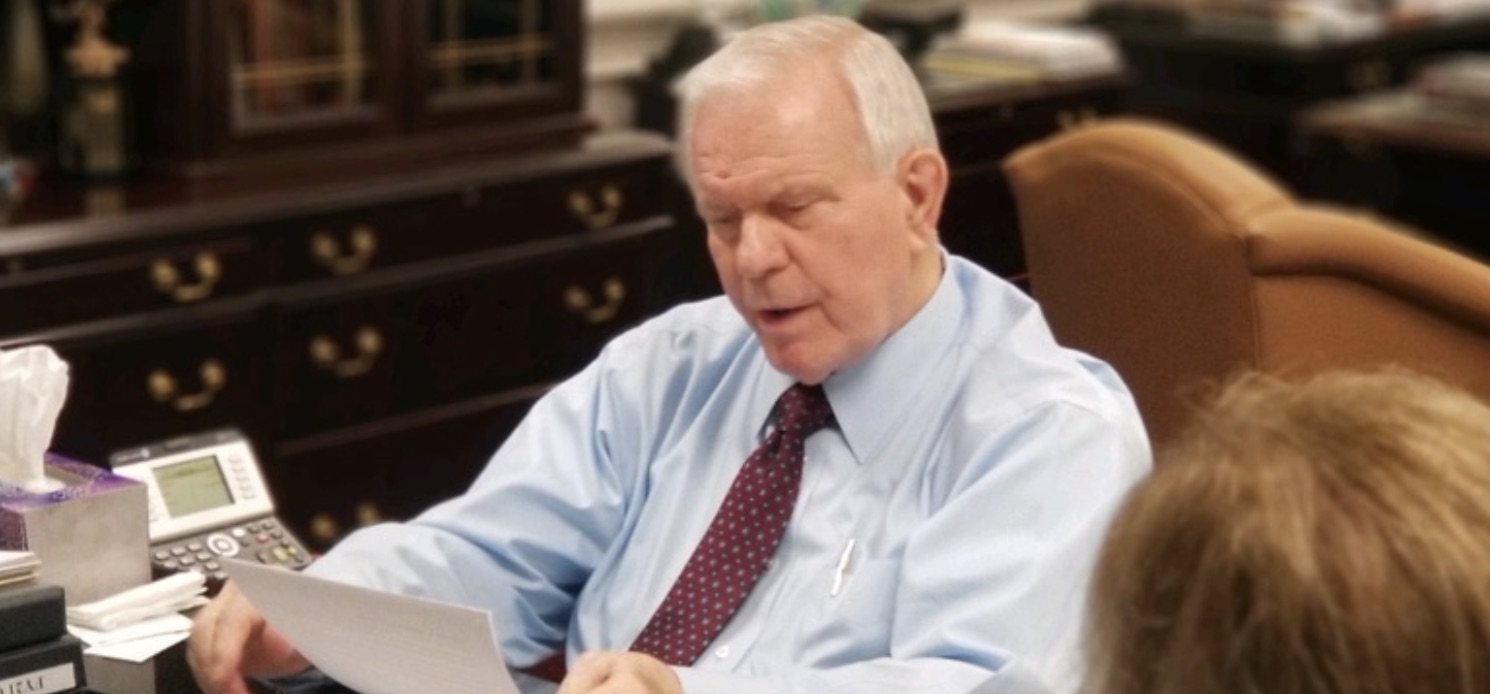

The board, however, is just one reason why the award-winning district northeast of Atlanta has long been recognized for its stability. In an era when urban districts see superintendents replaced every three to four years, J. Alvin Wilbanks has led the district for 24 years. Other top officials have worked in the district at least that long. That consistency has given Gwinnett schools “a golden reputation nationwide,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. But now, the onetime-Republican stronghold that voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 is calling for leaders who look more like the students and families in the majority Black and Hispanic district.

“This board has had the same members on it since I moved here,” said Marlyn Tillman, who came to Gwinnett in 2001 from another high-performing district, Maryland’s Montgomery County Public Schools. She now leads an advocacy group focusing on reducing discipline disparities and the involvement of police in student behavior issues.

But incumbent board member Murphy countered that residents view “continuity as vital to good governance” and that during her tenure the district has opened 79 new schools debt free and balanced annual budgets of close to $2.4 billion.

“Such achievements are threatened when voters focus only on political party, age, [and] ethnic and racial background rather than on a candidate’s judgment, experience, and trust earned over many years with the community,” she said.

Boyce, who is running for her fifth term, called Radloff a victim of bad timing. Georgia’s primary was postponed twice because of the pandemic. It was eventually held June 9, in the midst of protests over racial injustice — nationwide and in Atlanta.

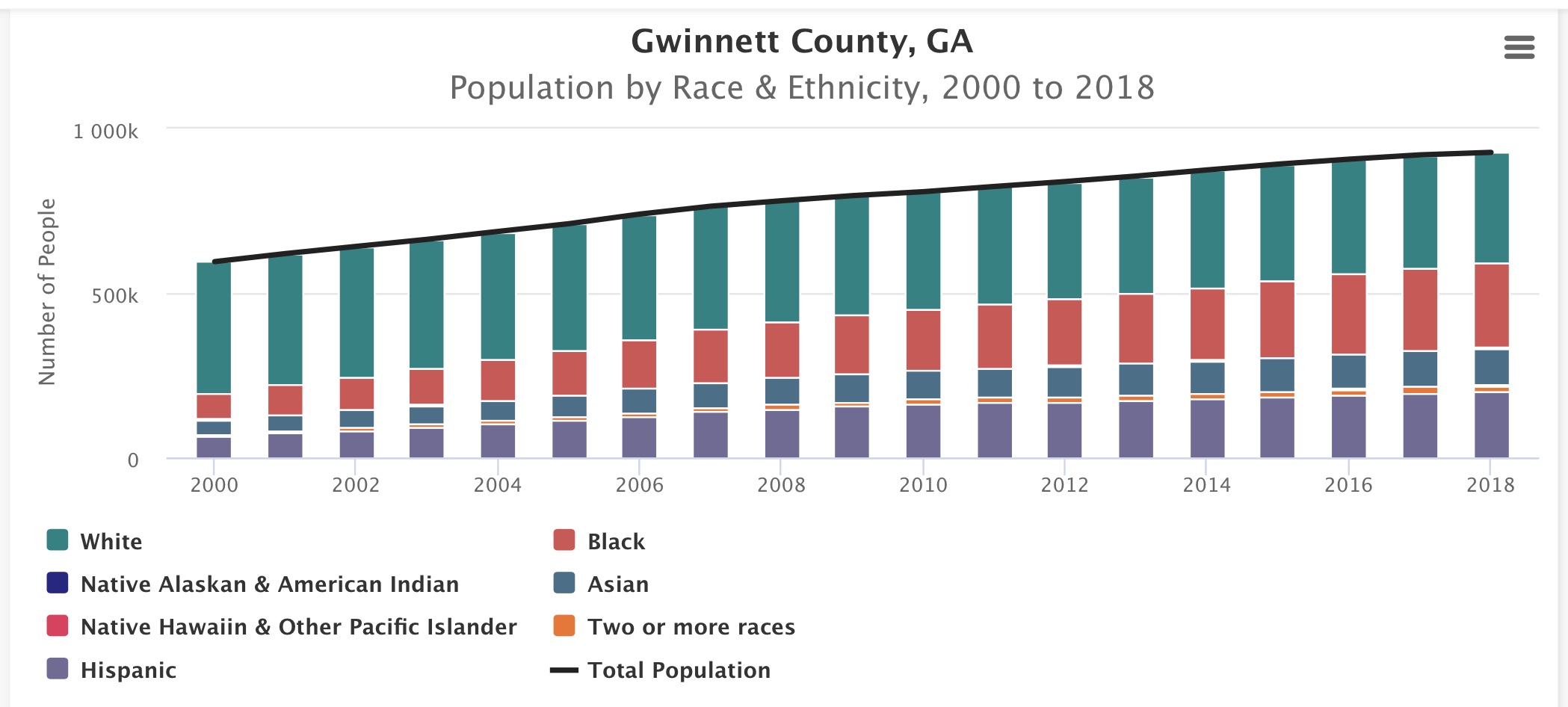

When Radloff joined the board in the early 1970s, Gwinnett’s population was over 95 percent white. Now, the county is the most racially and ethnically diverse in the state and among the five most diverse in the nation.

“Population demographics have been shifting since 1990, but our leadership is just starting to follow that,” said Tommy Pearce, the executive director of Neighborhood Nexus, which tracks data on the Atlanta region. He also lives and grew up in Gwinnett, where in 2018, voters also elected the first Black and Asian members of the county commission.

‘What we have in place is working’

The quality of Gwinnett’s schools has long been the prime draw for families moving to the county. It is the only district to win the Broad Prize for Urban Education twice — in 2010 and 2014. The $1 million award, put on pause in 2015, went to districts that demonstrated strong overall performance while narrowing racial achievement gaps.

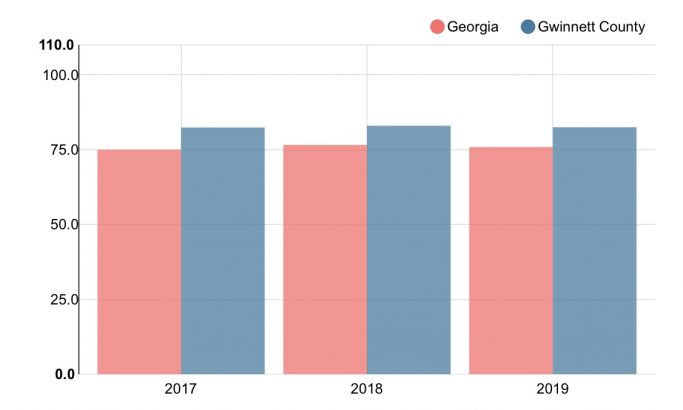

Historically scoring above state averages on tests, the district was posting double-digit declines in reading achievement gaps the first time it won the award. The National Council on Teacher Quality, the College Board, and Forbes are among the many other organizations that have given awards to the district for its performance.

Overall performance still outpaces the state, but recent data on the Georgia Milestones assessments shows less dramatic results than a decade ago.

“Black students do better in Gwinnett schools,” Wilbanks said. “That is a fact.”

Between 2015 and 2018, the district’s overall graduation rate increased to almost 82 percent, with the rate among Black students falling just a point behind. In 2019, both rates dipped slightly. The rate among poor students, however, has continued to climb, from 70 percent in 2015 to 75 percent last year. Gwinnett also has its own high school graduation test, which have been widely phased out across the country.

“What we have in place is working,” said Boyce, running for her fifth term. “It doesn’t need a wholesale, upside-down change.”

‘Accepting gaps’

In his first year on the board, Blair, who previously worked with superintendents across the country as part of The Broad Academy, felt he was supposed to “be honored by how excellent we’ve been.”

But he likes to ask pointed questions about the performance of nonwhite students. Even with a record of above-average performance, gaps remain.

“We can do a lot better still,” he said.

He said if he can get Wilbanks to make a recommendation, his fellow board members are more likely to support it. “He and I have a lot of respect for each other,” Blair said. “He has known me since I was in high school. Now I’m one of his bosses.”

With its record of above-average performance, Gwinnett was among the first districts in 2019 to receive flexibility from some state regulations in return for setting — and meeting — higher student performance goals But Tillman’s group and others argued that the district set lower goals for English learners, students with disabilities, and Black and Hispanic students. The coalition filed a civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Education in 2011. Currently, the district “remains under investigation for possible discrimination,” according to a department spokesman.

Incumbent Murphy noted performance gaps within subgroups also exist. She said she’s proud the board last year appointed a former high school principal, Tommy Welch, as its first chief equity and compliance officer. Welch, Wilbanks said, has been examining existing policies with equity in mind. One recent change shifts more funds to schools with the highest poverty rates.

The district also has a growing number of theme and academy schools that Wilbanks and Murphy said are an effort to allow more choice and expand opportunities for students.

Warning of a ‘revolution’

Reflecting conversations nationally, the role of law enforcement in schools has been a frequent topic at candidate forums. Johnson, Watkins, and Banks all argue that they wouldn’t completely dismiss school resource officers, but would reduce their number and add more counselors and social workers.

Johnson said she was encouraged to hear Wilbanks recently acknowledge that Black and Hispanic students in the district are suspended, expelled, and referred to police at much higher rates than white students.

“He gets it,” she said. “Hopefully we, with Wilbanks, can address it.”

Johnson said she has “a passion” for multicultural and multilingual education, but added that conservatives have labeled her a Black Lives Matter activist for discussing issues such as anti-bias training.

Among those concerned is Boyce’s husband Peter Boyce, an attorney who has trained the district’s police officers. Speaking at a United Tea Party of Georgia gathering, he called Johnson “scary” and warned that the challengers want “a revolution.” In addition, a campaign ad created by the Family Policy Alliance, a conservative Christian organization, said electing the challengers would lead to increases in teen pregnancy, “unsafe schools and Marxism taught in the classroom.”

The ad asks voters to support George Puicar — a HVAC technician and theologian — as a write-in candidate for the seat Johnson expects to formally win Nov. 3. Republicans didn’t have a candidate in the race because they had been generally pleased with Radloff’s positions over the years.

‘No conversation is off the table’

Some teachers in the district are calling for more attention to diversifying the workforce and the curriculum. Gwinnett Educators for Equity and Justice, which formed in June, presented district leaders with recommendations such as recruiting more Black teachers and requiring all middle and high school students to take a course on Black history and African studies.

Banks said she wants to represent staff members who feel their concerns haven’t been heard. “There is a whole culture that has been created to keep the narrative the way they want,” she said. “When you peel the layers of that onion back, and your eyes start to cry, there’s a reason for that.”

Domenech, with AASA, said he can empathize with the challenges facing Wilbanks. The two met when Domenech was superintendent of the Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia. His district, he said, was going through a similar transformation. “All of these large county systems have gone through demographic changes,” he said. “The only solution is to bring people together.”

Earlier this year Wilbanks’s contract was renewed through June 2022. After 55 years in education, he said he recognizes some people want a change. But some staff members are nervous about the outcome of the election.

“I have never worried about my job. I’ve never been fired from a job. I still enjoy going to work everyday,” he said, adding that whatever happens, “I will be ok.”

Blair said he can’t predict whether Wilbanks might be eyeing retirement or would like to stay on for a few more years. But with the potential for four Black board members, “no conversation is off the table,” he said.

“This is an exceptional school district, but it’s not perfect,” added Johnson, who is unfazed by Puicar’s write-in campaign and is already thinking about her own future on the board. “I think there should be term limits. The world changes. Perspectives change. I should not be here for 20 years.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)