A High-Poverty High School in Tennessee Is Using National Student Clearinghouse Data to Fuel a Revolution in Smart College Counseling

Chattanooga, Tennessee

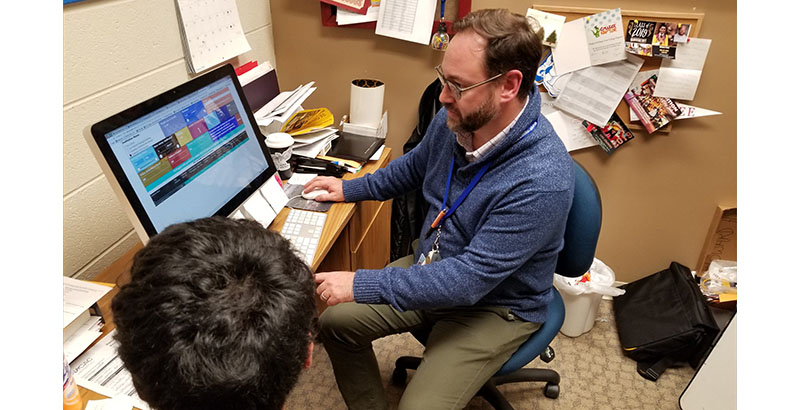

Inside a small, cluttered office at the high-poverty Howard School here, college counselor Nicholas Siler wields a powerful software tool that greatly boosts the odds the students he counsels will successfully complete college.

I watch while Siler calls up a student’s individual data on his easy-to-navigate dashboard. It reveals things that two years ago were not revealable. For black students, for example, he can now instantly identify colleges where graduation rates for black Howard alumni are above 50 percent.

Siler is at the pointy tip of a revolution so new that many high schools around the country are not even aware a revolution is taking place: Combining powerful data with finely honed college match tactics, which means finding a college where the student is most likely to earn a degree. It takes college counseling out of the dark ages where students routinely get sent off to colleges that are little more than failure factories.

These practices got pioneered at the top charter school networks, which used them to drive up college graduation rates for their low-income, mostly minority graduates — students who, in years past, never fared well in college.

Now, those practices are getting adopted by some traditional districts. Soon, high schools will divide into new sets of have and have-nots: Schools that offer smart, data-driven counseling fueled by alumni track records supplied mostly by the National Student Clearinghouse — a nonprofit that can tell districts exactly how individual alumni fare in college — and schools that don’t.

At Hamilton County schools, the impact is striking: College enrollment is up sharply (now at 73 percent), and college graduation rates at the six-year point (now at 55 percent), figures that you might expect to see in a far wealthier district.

How much of an outlier is Chattanooga? Several school districts — Chicago, New York, Washington D.C. and Atlanta come to mind — are getting pretty sophisticated at turning over Clearinghouse data to their counselors, almost always aided by friendly nonprofits that help them crunch the numbers. In Chattanooga, the far-sighted Public Education Foundation plays that role.

But these districts are themselves exceptions. Most school districts are flying blind. Last year, RAND surveyed principals who are part of their American School Leader Panel. What they learned from the nationally representative sample of 750 who responded: Only a third had access to individual student data on college enrollment.

Why is that important? Because when schools can’t tell which of their students enrolled they can’t adjust their instruction and counseling to make things better. Principals may know they have a problem, but they lack the tools to fix it.

The same is true around college remediation classes: Only 15 percent had individual student data on who ended up in remedial courses (which detour many vulnerable students who can’t afford to take classes that don’t award college credit).

Again, no tools to fix the problem.

Finally, the survey showed that less than a fifth of the leaders knew which of their students earned bachelor’s degrees within six years — a must-have data point for any district taking responsibility for the fate of their alumni.

For all three data points, enrollment, remediation and graduation, far more school leaders had access to aggregate data about their alumni. But without individual data — knowing exactly which students succeeded or failed — school leaders can’t design smart interventions to improve those rates.

One reason K-12 leaders hesitate taking this on: Traditionally, high schools haven’t considered college success as part of their mission. Isn’t that up to students, parents and the universities? We have enough on our plates!

True, they do have enough on their plates. But in an era when college is the new high school — many middle-skill jobs that never required college now do — high schools have no choice but to embrace the future.

In Chattanooga, Siler can’t imagine life as a college counselor without that data. One quick example: For Howard seniors who are looking for a historically black college within a reasonable driving distance, he feels comfortable steering them toward Talladega College in Alabama. Why? Because while federal records show the graduation rate there for low-income students at 50 percent, Siler has insider data from the Clearinghouse: Pssst! For Howard graduates, the success rate at Talladega is 87 percent. Go there!

“The Clearinghouse data is incredibly valuable,” said Sarah Malone, lead college and career adviser for the 45,500-student Hamilton school district. “We’re sending them to colleges where they are more likely to earn degrees. We want our students to get to and through college, not just to college.”

The push to get school districts to take some responsibility for the fate of their graduates is so new that only a handful of experts have a sense of what’s happening nationally. One of those is Kimberly Hanauer, who runs the education consulting firm, UnlockED.

“When we give school leaders data about college enrollment and whether those students end up earning degrees, they are able to take action. In some cases, they partner with a local college where their students struggle to earn degrees and work together to turn that around. Or, they can identify a college where their students successfully earn degrees and learn from that college.”

Hanauer is the former director of college prep for the District of Columbia Public Schools, which, along with Chattanooga, is one of the few school districts in the country pioneering data-based college guidance.

In Chattanooga, the Public Education Foundation started investing in education data many years ago, mostly as a diagnostic tool. Their intent was to measure which education interventions worked, which didn’t.

But foundation and school officials quickly realized that the real value lay elsewhere. “The data are not just about measuring impact,” said Dan Challener, foundation president. “The data open the eyes of both students and parents to the opportunities out there.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)