$8 Billion a Year on Ed Tech, but Does It Work? Experts Call for Better Research at Unique D.C. Symposium

Washington, D.C.

The $8 billion–plus ed tech industry has ballooned in recent years as tech tools flood K-12 and higher education to adapt classrooms now largely occupied by digital natives. The primary source for federal ed tech funding under the Every Student Succeeds Act is authorized at $1.65 billion. And while investments in the market slowed last year, private dollars continue to drive massive growth and innovation in the sector.

But in an industry that raised more than $1 billion across 138 venture deals last year, there exists an incongruence in evidence to support that explosion of investor and consumer confidence. Also missing is purchaser demand for proof that these innovations work once they make into the classroom. Experts believe, however, that better ed tech research would likely be driven by demand from schools and districts, and not because investors and tech companies seek evidence to grow business.

(The 74: #ShowTheEvidence: Building a Movement Around Research, Impact in EdTech)

In a new study of 63 ed tech companies, 90 percent of respondents reported that they were very or extremely confident that their product has its intended impact, while just over half of those who made claims of efficacy had research to back up their assertion. Overlaid is the finding that only 48 percent of consumers inquire about the relevant research.

“Most surprising to us – only about half of the school districts actually asked for evidence,” said Mahnaz Charania, director of strategic planning in research and program evaluation for Georgia’s Fulton County Schools. “We’re not asking the right questions. So hopefully this research will get us to say, ‘We need to look at this a little deeper and figure out what we need to do about this big gap in what we call quality and what we call evidence.’ ”

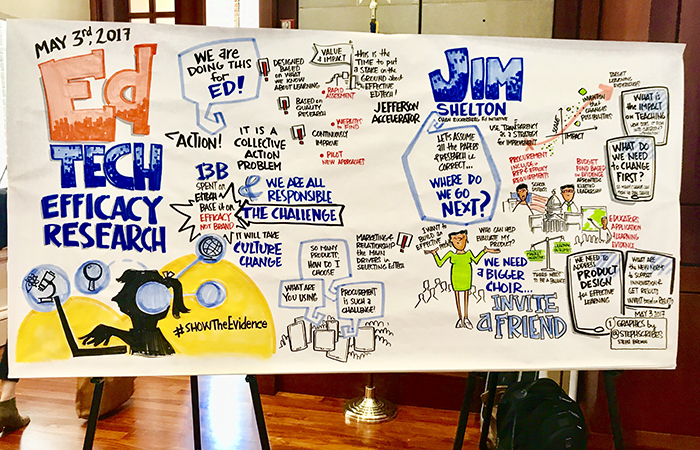

The research was presented during the first day of the two-day EdTech Efficacy Research Academic Symposium Wednesday in Washington, D.C. The findings come from just one of 10 working groups identifying, analyzing, and prescribing recommendations for the role of efficacy research in ed tech development, implementation, and decision-making across sectors. The symposium – hosted by the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education, Digital Promise, and the Jefferson Education Accelerator — brought together 275 researchers, teachers, entrepreneurs, professors, administrators, and philanthropists with a focus on actionable solutions.

Charania and David Daniel, a professor of psychology at James Madison University in Virginia, led the study. Also among their findings, 57 percent of ed tech developers reported conducting their efficacy research internally, while 20 percent said they use third-party evaluators. And in assessing their products, most companies don’t conduct efficacy research during product development, instead favoring user feedback and engagement data to improve a product over time. Just 42 percent of respondents said they have a standard process for evaluating the impact of their product.

“Our findings suggest that ed tech developers value research to inform their products but, for a variety of reasons, are not conducting rigorous research,” Charania and Daniel write. “Although most developers are focusing their outcomes on implementation fidelity and ease of use, these important aspects must be viewed as a start towards rigorous research and not the end goal.”

The rigorous research that Charania and Daniel call for still faces obstacles. The pace of the research cycle is slow — at times requiring years — and some of the best-researched technology often becomes obsolete after surviving the extended process. Researchers for a second working group found that nearly 90 percent of respondents to their survey did not insist on research evidence to make an ed tech purchasing or implementation decision.

“We need a paradigm shift in terms of how we’re working with schools,” said Michael Kennedy, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia and research lead on that study. A universal ratings system could be a solution, he said, to create more accountability in the sector.

Not only are those purchasing decisions often made without the basis of evidence, they’re also frequently the result of lip service paid by colleagues or counterparts in neighboring districts, a third working group found.

“Politics affect decision-making more than cost, effectiveness, or any other rational input,” working group lead Fiona Hollands said. Hollands is associate director and senior researcher for the Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education at Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York City.

The confidence and assumptions that trusted associates rigorously test recommended technologies are often misplaced, said Bart Epstein, founding CEO of Jefferson Education Accelerator and an associate professor at the University of Virginia’s education school.

Companies know that products multiply through and across communities as a result of that proximity, and Epstein said developers frequently ask him who key influencers are, or whether he can connect them with major school districts. If those mammoths pick up a particular product, it’s more likely to succeed.

Particularly in a torpid ed tech market with capricious investors in the driver’s seat, the onus is on researchers not to influence backers on the supply side but to develop educated mechanisms that foster collaboration and move the needle with schools and districts on the demand side, Epstein said.

“When you ask them publicly, every ed investor will only want to fund the things that work – they’re mission-driven,” Epstein said. “But if you ask them behind closed doors, they’ll tell you that unless they have specific social capital given to them by a foundation or family office, they invest in what provides returns. When research drives returns – meaning more sales – investors will do it.”

“Until then,” he added, “it’s not a … productive use of our time to cajole or guilt investors into doing more research. What they’re doing is generally more rational. Investors tell us over and over what they want is smart consumers. We need better consumers. We need better tools to support our consumers so they make better decisions.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)