74 Interview: Former North Carolina Gov. Bev Perdue on Educating a 21st Century Workforce & the ‘Most Horrific Public Discussion’ She Ever Heard

See previous 74 interviews, including former U.S. Department of Education secretary Arne Duncan, Teacher of the Year finalist Nate Bowling, and two Texas middle schoolers who seek an end to gun violence. The full archive is right here.

At 71 years old, Bev Perdue is championing one thing: technology for education and the future workforce.

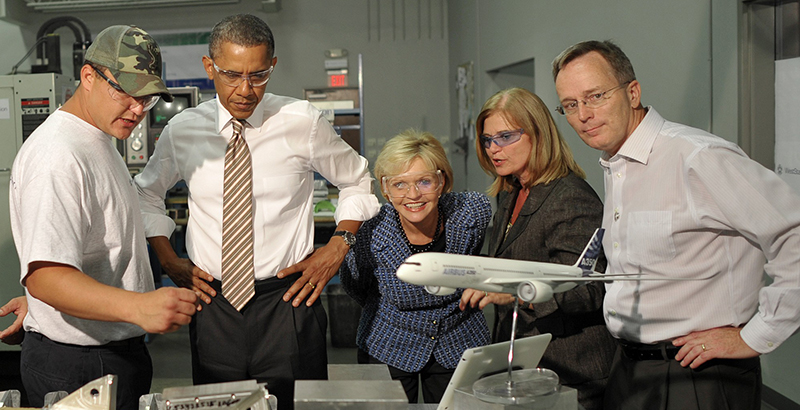

Perdue served as North Carolina’s 73rd governor from 2009 to 2013 and was the first woman elected to the state’s highest office. She saw the state through the aftermath of the Great Recession and focused her policy on bolstering education and creating jobs.

Throughout her decades in public service — in the North Carolina legislature, as lieutenant governor, and as governor — Perdue has focused on improving graduation rates and strengthening the pipeline that sees students through college or career training after high school. She also led the state to invest in education technology, fostered public-private partnerships to integrate that technology into North Carolina’s schools, and created a statewide broadband education network for public schools and institutions of higher education.

Now, five years after her term ended, those priorities still very much sit at the top of her agenda, and she says the imperative for technology-forward education is even more urgent.

“We’re still very much at risk in a different way because of technology and machine learning. But I think the risk is probably more grave,” Perdue said in an interview with The 74. “If you look at the data about the underserved communities we’re not educating, we’re losing about 50 percent of our future workforce. I think that’s frightening in a global economy.”

Perdue has taken those issues on in her time after office, serving as a fellow at Harvard and Duke universities, working as an education consultant, and co-founding and chairing digiLEARN, a nonprofit that works to expand personalized learning and technology business collaboration.

Perdue recently sat down with The 74 to talk about the future of work and what needs to be done in education to ensure a skilled workforce for generations to come. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The 74: How do you get around the rural-urban divide in states like North Carolina?

You can’t get around it; you have to go through it. There has to be a commitment to an infusion of money and well-trained teachers and services and workforce preparedness. We know what works; we’ve just got to take it on and know that it might take a 20-year time span. The money has to be scaled and sustained, and that requires grit, because it’s not sexy, it’s not fun to do that kind of work. But that’s the way we save that part of the state.

What is the intersection of public and private sectors to ensure a skilled workforce?

I don’t think you can do it without the collaboration of the private sector. It’s too sophisticated. Back in the old days, when I was a teacher in the ’70s, all I needed was a chalkboard, a pencil, 30 desks, and some books. We could get it done because the times were simple and the challenges, although daunting, weren’t enormously daunting. And they didn’t require complex thinking, didn’t require the collaborative risk-taking mindset that we know this current workforce and this current generation of students have got to develop. We know what needs to be done, and we need to go to work and attack it. It can be fixed. The whole country can be fixed. Adults don’t know what’s about to happen to them.

How do we prepare for a workforce we don’t know about?

You have to be a risk-taker. You have to be adaptive. You have to be willing to fail. You have to have the skill sets, the basic knowledge — the math, the reading, and English — the kind of tools we’ve always needed if you’re going to be upwardly mobile. There’s always going to be a plumber, there’s always going to be an electrician, but for the truck driver, or the waitress, or the bank teller, or the accountant, or the lawyer, those jobs are going to be absolutely done away with or transformed. That’s where the new model becomes so essential.

There has to be the ability for educators to understand that group thinking is not the way we need to teach anymore. We need to let little girls know they are in power, and we need to let boys know the future is wide open for everybody, but you’re not always going to get the trophy. Some days you’re going to fail. You have to be willing to fail, and you have to have both academic and soft skills.

The thing that annoys me to death is when somebody comes in and they don’t look me in the eye, they don’t know how to shake my hand, they don’t know how to talk in an interview. Those are the skill sets that we need to teach everybody, including people who are now in their 60s who may have to retool.

I’m not so worried about kids in school, and I’m not so worried about folks on the career and college trajectory, but I really do worry at night about what’s going to happen to your granddaddy or my granddaddy, because they’re the ones that are going to lose their jobs. They don’t know what’s going to happen. How do we do that? We do it with technology, we do it with community help. But we’ve got to be prepared.

What’s the kind of technology that can prepare them for that?

I don’t think there’s a better tool in the world than personalized learning. You’ve got to have some kind of human involved. You’ve always got to have a good coach and a good teacher, but I really do believe that the digitalization of learning and teaching is changing the world.

Whose responsibility is it to let the current workforce know the age of automation is coming?

I do think you need a great leader, whether it’s governors across the country, whether it’s a huge philanthropist. I don’t know who the entity will be, but I know that for the past three or four years, from my perspective, education has not been a national imperative, and it does not seem like business leaders, policymakers, and academics across the country are focused on how you translate the reality of the new workforce to real people. I’m very troubled by it, and I do think it can be done, but it’s going to take somebody with money to communicate it. And it’s going to take somebody with a voice, or a group of entities with a voice, and then I think it’s up to the states and the feds to help fund it.

It happens all over our country — in Texas last year — that when storms come, when a terrible recession comes, when an industry closes, the federal government with workforce money has stepped in and just piles money and opportunity. We’re going to have to do that on steroids for the workforce.

Why do you care so much about education?

I was poor as a little girl. My dad was a coal miner, my momma didn’t have an education, and they wanted better for my brother and me. And I had this teacher, this one woman changed my life. She told me I could be more than I thought I’d be, but it was going to require some grit — persistence and conscious learning. I didn’t know those words, but I knew I wanted to be somebody.

I don’t care whether it’s public or private, you’ve got to have an opportunity to get an education. So I believe in every little boy and girl, and nothing makes me angrier to see us sit back and see kids who are disadvantaged fail. That’s wrong.

How much can a governor do if a community isn’t responding?

One of the things that’s great about being a governor or a leader that’s respected is that people will listen. They may not agree, they may not internalize your comments, but they will be respectful or polite enough to listen.

Governors are absolutely focused on creating jobs. The whole country is focused on creating jobs. We have a president who can’t talk about anything — anything — but he does talk about job creation some. It doesn’t take much age or much maturity for a 14-year-old, who is applying for a work permit, to realize when he goes to McDonald’s to fill out the application, he needs to be able to read and write, and he needs to know a little bit about technology because the computers and the service systems are all automated. They make a milkshake now by computer. He has to understand that.

It doesn’t matter what industry you’re recruiting to grow in your state, the one question that was consistent with me was, “Tell me about your schools.” Every mom and dad who is going to relocate to your state to work wants their kids to be in a safe neighborhood, good schools, good colleges. So they’re interconnected in such a deep, meaningful way. You can’t do one without doing the other.

How does the president’s talk about jobs creation align with his administration’s desire to cut funding for education?

From what I’ve seen of this administration, there is a tendency to want to break down the existing educational structure. And I don’t think that’s bad if you break it down with a reason and with a purpose, and you’re not doing it just to replace something. I’ve been a supporter of charters and other new initiatives for more than 15 years, but I also want them overseen, and I want data collected on the outcomes for students, and I want to shut down the bad ones.

I think hand-in-glove the work we do with the federal government is really important for how education happens in communities, and I think this administration has not understood clearly that the signals they’re sending don’t bode well for the public and many of the private schools in America.

I do think, though, that it’s time that we challenge the institutions of higher learning. I love badging and credentialing. I love being able to go at your own speed from maybe second or third grade if you’ve got a level playing field. So there’s no such thing as seat time. I want to see that happen. I’ve worked on that for more than 20 years. I want there to be competency-based learning so that if I can do fifth-grade math, then I’ll start doing sixth-grade math, and if I can do everything that my high school offers me and I’m only 16, I should be able to exit that school and do whatever else I want.

If I am going to a postsecondary institution, if I don’t want to do four years, if I have the personality and the skill set to want a different pathway, I want there to be a whole plethora of badges and credentials bundled online. Then I can take them — including my military experience — to places like Cisco and Pearson, and show that I may not have a four-year degree, but look at all this.

So I think another national imperative — and global imperative — is for someone to figure out how we’re going to do the certifications, how we’re going to consolidate some quality control, and then how we’re going to certify that they’re legitimate so employers can begin to see another pathway besides the college degree. That makes a lot of people mad.

For someone in their 40s and 50s who has to go back to school to learn new skills, who is paying for that?

I was involved in Pillowtex, a company in Kannapolis that made sheets, towels, and underwear. It was a huge company that had 5,000 workers, and most of them had been there for generations. One day they all came to work and there were pink slips in all their mailboxes. They had no warning: The company declared bankruptcy overnight, and 5,000 families were without an income.

We encouraged the federal government to give us money. And they did. Through the Labor Department, they allowed us to pay for all the job retraining that it took for several years in that community, whether it was in a community college or a certificate program.

I can remember one of my best experiences in public service. I met this man in the early days of the company’s closure, who was maybe 50 at that time. He talked to me about what he was going to do with his life. And he told me he was going to be OK, that he’d go back to school, because there was money to support the family and pay the rent while he transitioned from unemployment.

It’s a great system, and it works for people who are in dire straits. Two years later, I came back to that community, and that was about the time that we opened David Murdock’s research campus in Kannapolis.

The same man remembered me, came over, hugged me, and he said, “Look at me, I told you I was going to be OK.” He had done an 18-month certificate program that taught him how to be a biotechnology lab assistant that processed what they needed to grow new food. He was so proud of himself. There will be millions of those stories in the next 20 years about how individuals are persistent and conquer adversity. That’s the story of America.

What worries you most about the younger learners?

Pre-K is where I start. I think every child in America needs to be in a quality preschool program. The data is clear on that: Early childhood changes a kid’s trajectory for his whole life.

I’ve got two grandsons who are in the best preschool in North Carolina, and it’s a diverse school. I compare them to other little children who aren’t in preschool — from rich families, from poor families — and there’s such a difference in social and thinking skills that you know it works. So the data is there, but you also know analytically, anecdotally, that it works.

For K-12, I think if you can personalize learning and if you have good teachers, which we’re not doing in many schools in North Carolina and in America, I think the opportunity is there. The thing we don’t focus on is the at-risk kids. I think schools, public and private, have to change. They have to be more acclimating to a student’s needs, and that no longer can you have a classroom of 26 kids or 36 kids who sit at their desks and are preached to all day. So I love the whole concept of the interaction in the room, the coaching, the things that are happening in many schools across the country.

Teachers are willing to do that, so I’m not worried about that, either. I am very concerned about the adult learner and the fact we think that it’s seat time for kids that counts, that you don’t graduate until you finish 12th grade. I think that mindset has to clearly change.

Immigration is a huge issue in North Carolina. How does that intersect with childhood learning, adult learning, and a skilled workforce?

The present conversation about shutting down America’s borders is the most horrific public discussion I’ve heard in my lifetime.

I wasn’t knowledgeable of the hard times in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s. I didn’t live in the South then. So I didn’t see those times that were perhaps more distasteful, more complex, more painful for a country and for a state. But when I see children who are here as Dreamers, or I see children who are really competing in a first-grade class, when I learn that the momma is learning English as the kid goes home, my heart smiles. That’s the America that I love that promises opportunity and access and success for every family. For kids to be afraid to complete a census form, it just says ugly things about who we are as a people.

I find in my state especially that you can go into schools that are high-proportion immigrant, and the teachers are doing amazing things. The principals, perhaps contrary to public policy, are finding the resources to help these families and children. On Fridays, when we send backpack lunches home, if you watch very carefully you’ll see an extra two, three lunches go in the backpack because folks in that community know that the family is hungry as well as the child.

I did a forum at Duke recently about immigration and Dreamers. One young man in his 20s about to graduate from Duke’s medical school stood up. And he said, “Governor, what about me? I’m going to be kicked out of the country, what about me?”

That question in the 21st century in America is a wrong question. The country should be embracing him and helping him.

During your time as governor, you saw a lot of immigrants in the state’s economy. What role do they play?

They are an essential part of our economy now at all levels. Where I live in the Triangle, I go to my grandkids’ swim teams or soccer games, and 95 percent of the kids are from somewhere other than America, and the nice thing about that is nobody knows the difference.

So I think that for the younger generation, everything is going to be OK. I think when my generation kind of, goes away — I don’t mean to the grave, I mean just get out of the way, but we’re the ones who have the stereotypes, and we’re the ones who have perhaps the implicit embedded racism or sexism, all of the -isms that we don’t know we have.

You couldn’t have an economy around technology, medicine, law, any of the professional services without immigrants and non-native English speakers. Agriculture is the driving force in the economy in eastern North Carolina — there would be no way to have an economy there and in any rural parts of western North Carolina without a very blended workforce. That’s critical to getting things done and putting food on the table.

Across America it’s the same way. The real estate industry, the home builders, you couldn’t build a house without hardworking men and women who want a job so they can help their kids have what you and I have. It’s all about the dream. So I think it’s healthy for our economy. I don’t see any examples — show me an example — of a displaced native American, indigenous North Carolinian who’s lost a job because somebody from some other country came here, unless their preparations and qualifications were better.

What do you think that we as Americans are getting wrong the most?

First, I think what we’re getting right the most is the fact that we continue to focus on education and to fund education. I laughed during the recession of 2008 that the only sure thing in my budget or in President [Barack] Obama’s budget was the military and education.

Those are the two givens — you can’t take that away. So there’s this historical, deeply embedded, long-term commitment, and it’ll be a future commitment. There will always be initiatives and work-around education, and that’s a very good thing, because it drives economy and it actually determines the future of our country.

In a global economy, the world looks very different, and I think that’s what we’re getting wrong. I can’t speak for all the states — I would think that Colorado is much more aggressive and liberal and perhaps has addressed it more directly in their state — but in all 50 states, we’ve got to admit that when you look at the international scores on PISA, and you see the countries that are so far ahead of us, that’s a problem to me.

I still think of America as always forever being the supreme economy and the supreme country that leads the world, and the country that becomes the world’s keeper in times of stress and in times of challenges. I like that kind of image. I worry that someday we’re going to wake up and it’s going to be too late. That we will have to say, “Why weren’t our eyes open? And why didn’t we work harder to secure our place as the leader of the global economy?”

Is there anything you’ve wanted to get off your chest?

I’m troubled, now that I’m 70 years old, and I look back at the sexism and the racism. It’s hard for me to believe that things have not gotten better, that it’s still wrong.

I’ve never worked enough on the women’s issues, but I have become more outspoken. Part of a chapter of the book that I’m having written is about how hard it was for me and how hard it is for other women to be in elected office. Look at Hillary and the subliminal judgments people made — and the fact that it’s hard for people today to see a woman in a place of powerful leadership. It’s not so hard in Congress, but when it becomes the No. 1 seat in a state, or in a country, there’s a question, “Can she do the job of a man?”

I think the physical differences in a man and a woman are striking. For years, my team would bring in an apple crate for me to stand on so I could at least be at [the men’s] eye level. But you don’t always have an apple crate with you, so I think those kind of subliminal cues in the differences in our voice, in the differences of our dress, and the things that are expected of us do a disservice to women of all ages.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)