46 Years After Divisive Court Order, Boston Schools Still Struggle to Hire Black Teachers

When Luther Joseney grew up in Boston, as he remembers, anytime one of his friends tried to sound academic, the response was quick: “Stop talking so white.”

Now, as a teacher in Boston’s James F. Condon School, Joseney knows that his very presence as a Black male signals to today’s students of color that they don’t have to limit their aspirations. “Before I open my mouth, that non-verbal affirmation is there,” Joseney said. A simple head nod, signifying that he sees students and understands their lives, can be profound.

“It’s difficult not to see me in you when I grew up two streets away from you,” he said. “Being a male of color affords me an opportunity to be a mirror.”

The importance of that mirroring is backed up by 15 years of research: Students with same-race teachers demonstrate higher achievement and rack up significantly fewer absences and suspensions.

But for most school districts, finding and keeping teachers of color has proved difficult. The issue has a unique resonance in Boston, where efforts to increase teacher diversity are part of the city’s reckoning with its racist past. In 1974, a federal judge ordered the Boston Public Schools to address decades of segregation by requiring its teaching force to become 25 percent Black — an order the city has failed to adequately meet over more than 46 years.

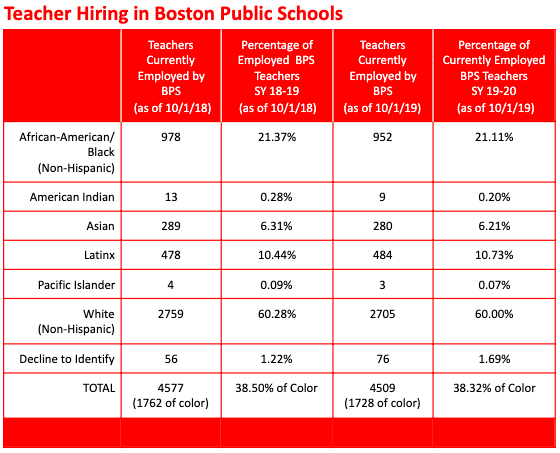

The ruling has pushed the district to embrace nationwide recruitment and robust retention efforts. In fact, Boston is actually doing better than most U.S. cities in this regard. More than 21 percent of its 4,403 teachers are Black, compared with 12 percent for the typical urban district, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Boston’s higher national standing despite the court order does not impress Joseney, a passionate educator, who said of the city’s hiring efforts: “We are failing the least.”

That 25 percent goal is “what we talk about every day — the things we can do to create pathways and pipelines to get [diverse candidates] into the classroom,” said Abdi Ali, the manager of two hiring programs for the district.

Those efforts could be put to the test in the coming years. Teachers hired in the initial wave after the ruling are retiring in larger numbers, and there are fears that the city’s progress could falter. Critics say they are more than ready to yank the district back into court, reopening the wounds of the painful suit that still taints the city’s race relations.

Race riots in Boston

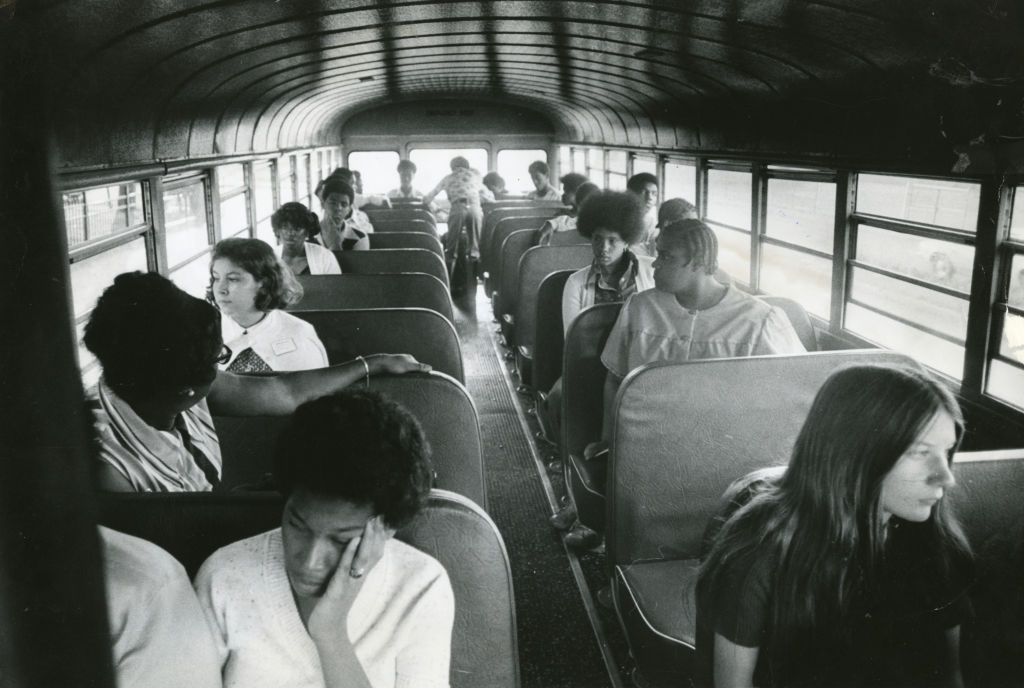

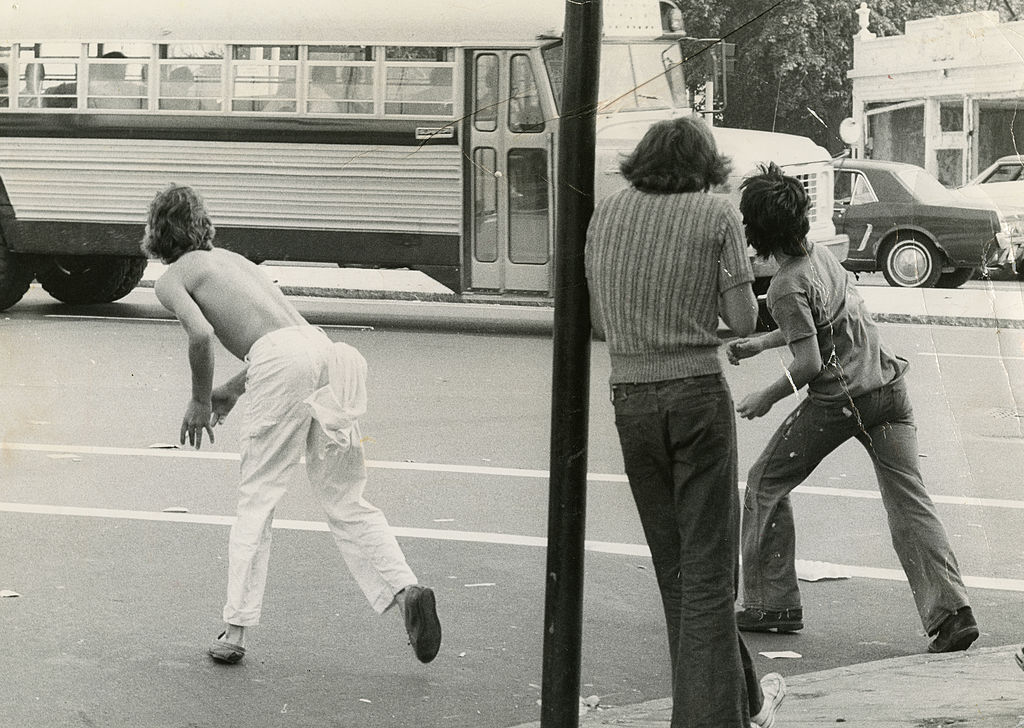

After years of protests that included the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s first civil rights march outside the South, the U.S. District Court in 1974 ordered Boston to desegregate its schools by busing both white and Black students outside their neighborhoods. At the time, 84 percent of white students attended schools that were more than 80 percent white, while 62 percent of Black students attended schools that were more than 70 percent Black.

In the case of Morgan v. Hennigan, Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. found that the school district “knowingly carried out a systematic program of segregation.” His order requiring the busing of 18,000 Black and white students led to violence and riots. On the first day of school following the order, buses carrying Black students in South Boston were targeted with eggs, bricks and bottles. Later that year, a Black student stabbed a white student at South Boston High School. Parents barricaded the school, trapping Black students inside until they were escorted out by state police.

While the ruling, and the violence that followed, are well known, the teacher diversity element of the decision is not.

The court listed three factors behind the district’s failure to employ more than 7 percent Black teachers: “discriminatory” cutoff scores on the National Teacher Exam, inadequate minority teacher recruitment and the city’s reputation as an “anti-Black, segregated school system.” Garrity called for Boston to hire one Black teacher for every white teacher hired until the district’s Black teachers constituted 25 percent of the teacher workforce.

“The teacher diversity component was an important part of Morgan v. Hennigan,” the 1974 court case, said Iván Espinoza-Madrigal, the executive director of Lawyers for Civil Rights.

It took the city 14 years to desegregate schools to the court’s satisfaction; the district’s plan was deemed “successful” by a federal appeals court in 1988, which in turn gave control of student placement back to the city’s school board.

But except for short periods that never lasted more than a year, the district has not met the teacher diversity goal.

“It’s a legally binding order which the district has not complied with,” Espinoza-Madrigal said. “We are certainly willing and able to seek legal relief in federal court.” But the lawyer and the suit’s plaintiffs, including the city’s NAACP chapter, would like to exhaust other options before reactivating the suit.

The district has not treated the requirement “as a standing court order for about 20 years, and that’s problematic,” said Tanisha Sullivan, president of the NAACP’s Boston branch. “They’ve treated it like an option versus a requirement.”

Falling short

Despite its unique history, Boston Public Schools isn’t alone in trying to diversify its workforce. Eleven states have pledged to increase their numbers of teachers of color to match student populations by 2040, but a recent report predicted that these gaps will persist or grow through 2060.

Boston’s push is occurring against the backdrop of a nationwide shortage of teaching candidates. From 2008 to 2015, there was a 15 percent drop in the number of students who earned an education degree, according to a 2019 study from the Economic Policy Institute.

Even with pay that can net a teacher $100,000 after about seven years in the district, Boston faces competition, both in-state and nationwide. Although the district employs 47 percent of the state’s teachers of color, that has only allowed it to maintain the status quo for the past five years. It currently has 21.1 percent Black teachers.

Barbara Fields, of the Black Educators Alliance of Massachusetts, one of the plaintiffs in the 1974 suit, blames the stagnation on a lack of consistent district leadership. Boston has had four superintendents in the past five years.

Fields worked in the district’s Office of Equity from 1981 to 2007. It was during her tenure that the district’s percentage of Black teachers peaked at 26 percent, she said. Because this figure wasn’t retained, the district was unable to meet the court order.

But since her tenure, Fields said, the office lost its power to sign off on every hire in the district, denying it a chance to more closely hew to the one-to-one ratio decreed by Garrity. When she led the office, that sign-off meant Fields could question individual decisions, such as when a highly rated Black teacher wasn’t hired for a full-time position.

“Despite all the rhetoric and supposed commitment, they’re just not committed” to ending the court order, Fields said. Three-quarters of the Alliance’s membership are district teachers, she added. “We know [Black teachers] want to stay.”

This position is backed by Sullivan, who was the district’s chief equity officer from 2013 to 2015. “I absolutely believe it’s critically important [for the Office of Equity] to have sign-off authority,” she said. Looking through history, she said the only times the district has risen, albeit temporarily, above the 25 percent level for Black teachers was when the office had both review and sign-off power.

Changing demographics

The nation’s demographics have shifted radically since 1974. Students of color now outnumber white students in public schools, but the percentages of teachers of color — which include Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, Pacific Islanders and American Indians — have only inched up, rising from 13 percent nationwide in 1987 to 18 percent in 2012, according to a 2016 report from the U.S. Department of Education.

Ceronne Daly, Boston’s managing director of recruitment, cultivation and diversity, said that hewing to the court’s one-for-one order wouldn’t work for a district where students of color now make up 86 percent of the district. In 1974, the district was roughly 60 percent white students, according to the court decision. Now the 53,094-student district is only 14 percent white.

“We can’t recruit our way into increasing” the district’s number of teachers of color, she said, even though the district has recruited nationally for years, intentionally building connections with several historically Black colleges and universities. To reach the court’s goal, the city would need to replace about 170 non-Black teachers with Black teachers. In the past five years, the district has hired about 1,000 educators a year, roughly a quarter of whom have been Black.

Noting that some districts, including Washington, D.C., have lost up to 30 percent of their teachers of color, Daly said Boston is “doing a lot of paddling under the water to stay steady.”

She said the district avoids overt pressure to hire teachers of color, finding that dictating hires can result in awkward fits that end with more teachers leaving the profession quickly. But the district nonetheless expects principals to have staffs that match their student populations. Daly said her office’s goal was twofold: to get enough candidates of color in front of principals and to create a community where diverse educators can feel not only comfortable but valued.

‘When we recruit our own’

Whereas Boston had to be forced to confront its bigotry in 1974, today’s officials are up-front about where they stand. The second page of the district’s hiring update this year plainly states how the city has not yet met the terms of the court order. “I give them credit for not shying away from” it, said Espinoza-Madrigal. “We have to applaud their progress while also pushing for more.”

Daly’s office includes eight people and runs nine programs aimed specifically at recruiting a more diverse workforce. These programs aim to encourage and support community members and paraprofessionals to make the jump to becoming certified teachers. Forty-six teachers of color were hired this school year from these programs. The most ambitious initiative is the High School to Teacher program that identifies potential teachers as early as the seventh grade and then supports them through college with the goal of eventually employing them in Boston. Right now, the program has 55 participants, ranging from ninth-graders to college sophomores. Thirty of the group’s members are Black, and 12 of those 30 are in college.

“No teacher preparation program can keep abreast of our needs,” Daly said. “The next generation of teachers are sitting in our classrooms right now.”

Originally, the initiative identified students in high school, but it lost contact when graduates attended college. Daly revamped the program recently. The new program, which she said the district is “doubling, tripling down on,” will remain in contact with students throughout college, using the city’s contacts with state colleges and historically black colleges and universities to offer students access to those schools’ education programs and scholarship opportunities.

“We’re selfish. When we recruit our own, we don’t have a retention problem,” she noted.

Xyra Mercer, a junior at the Henderson Inclusion School in Dorchester, is part of this program. She attends afterschool meetings every two weeks where participants get tutoring help and then hear a talk about various subjects, from résumé-building to how to plan a senior capstone project.

She said her mother, who was born in Jamaica, made her aware of Boston’s troubled racial history. She acknowledged that she feels a stronger connection with teachers of color at her school, especially one who comes from the Caribbean. And not only does she plan to attend college and return to Boston to teach, she also has hopes to one day earn a doctorate and enter politics.

“People always told me I was going to be something big,” she said. “Teachers have a lot of impact on students. They are almost as important as doctors.”

‘The biggest issue is retention’

In addition to having fewer teacher candidates to choose from, schools nationwide have more trouble than ever keeping the teachers they have, especially in high-poverty schools. In 2012, 15 percent of teachers in high-poverty schools either left the profession or changed schools. Many teachers say they leave the profession because of poor preparation, lack of support and low pay, according to a report from the Learning Policy Institute.

When Travis Bristol, an assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley, studied Boston’s Black male teachers in 2012-13, he noted that half left the district during his research after facing the challenge of being “behavior managers” more than teachers and enduring poor working conditions in their schools.

Teachers who were the only Black males in their schools reported feeling isolated and disconnected from their campus’s core mission, Bristol reported.

“There is a supply issue,” he said, but the “biggest issue is retention.” Recruiting teachers and then having them leave the profession for a variety of reasons “is like trying to fix a leaky pipe with water.”

Daly said that issue has improved in the past five years. Two district groups that started after Bristol’s report, Male Educators of Color and Female Educators of Color, aim to increase retention and offer platforms for teachers to discuss problems and concerns. The nine-month programs connect fairly new teachers with older educators and university professors twice a month.

“It was so powerful to have this space exist when we went remote” during the pandemic, Daly said. Having educators of color meet online to process the country’s mood after George Floyd’s death “is hard to describe. Gallery view is a powerful thing in Zoom.”

Joseney described why the group was so valuable. “I definitely don’t have a problem speaking up” about race and equity, he said, adding that he has to guard against “ending up the ‘angry Black person’” at his school. In his male educators group, he said, he feels his opinion is valued and he also receives leadership training and professional development. “Every teacher that has left [the group] has been better,” he noted. “I have a support system, a brotherhood. [The district’s] retention efforts have been genuine.”

The numbers prove the programs’ worth: Over five years, 76 percent of men in the program have remained in the district, while the women’s retention rate over four years is 91 percent, Daly said. These programs also prepare teachers to move into leadership positions, with 14 teachers in the past five years gaining promotions.

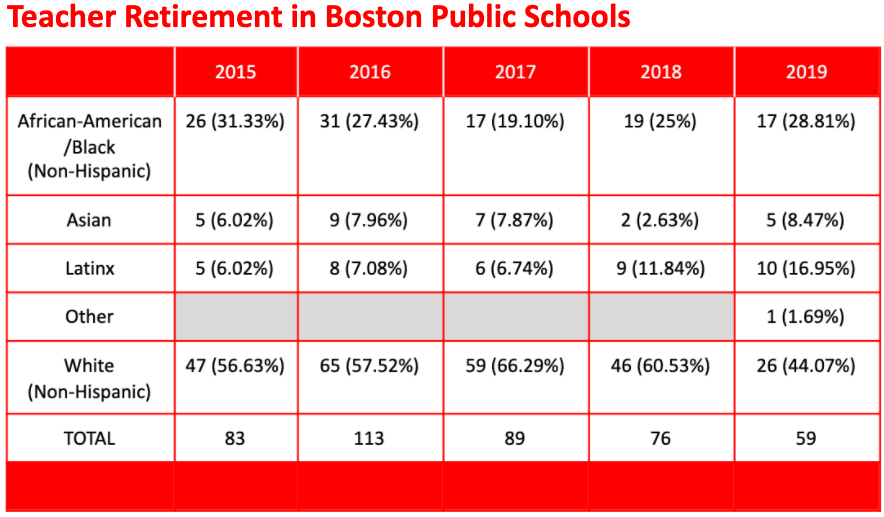

Still, even with additional recruitment and better retention, Daly fears that the district’s diversity might plummet in the years to come. The Black teachers who joined the district in the post-1974 hiring push are aging out of the workforce, she said. More than a quarter of the city’s teachers are 57 years old or older, and over the past five years, 26 percent of Boston’s retiring teachers have been black.

“We know what the next five years of retirement could look like,” she said.

She worries that uncertainty about teaching during a pandemic will hasten additional departures. Boston teachers returned on Sept. 8, but students won’t start remote learning until Sept. 21.

Daly recognizes that boosting the district’s Black teacher percentage and finally meeting the court order will be difficult. “The data tell us what the challenge is,” she said. The competition for talented teachers of color will increase, and these people “can work wherever they want. We need to make educators of color, administrators of color, see the value of staying.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)