10,000 Miles Away: For Students in Springdale, Arkansas, Home to America’s Largest Population of Marshall Islanders, School Can Be Something of a Culture Shock

Over the next several weeks, The 74 will be publishing stories reported and written before the coronavirus pandemic. Their publication was sidelined when schools across the country abruptly closed, but we are sharing them now because the information and innovations they highlight remain relevant to our understanding of education.

The incident occurred more than five years ago, but Benetick Kabua Maddison remembers it vividly.

He was in middle school in Northwest Arkansas when he overheard a teacher berating a classmate — like him, born 10,000 miles away in the Marshall Islands.

“Stupid Marshallese,” Maddison heard the teacher say.

“I don’t know where that came from or what made [the teacher] say that,” he said. “But it was infuriating, and I think that experience alone motivated me more to do better in school and to push my people to succeed in school and in life.”

Maddison’s “people” are the thousands who left the Pacific archipelago for Springdale, a town of 81,000 people located 20 miles south of Bentonville, home to Walmart’s headquarters. Pushed out by the lingering effects of American nuclear weapons testing and the rising tides of climate change, the Marshallese transformed the demographics of the Springdale School District upon their arrival.

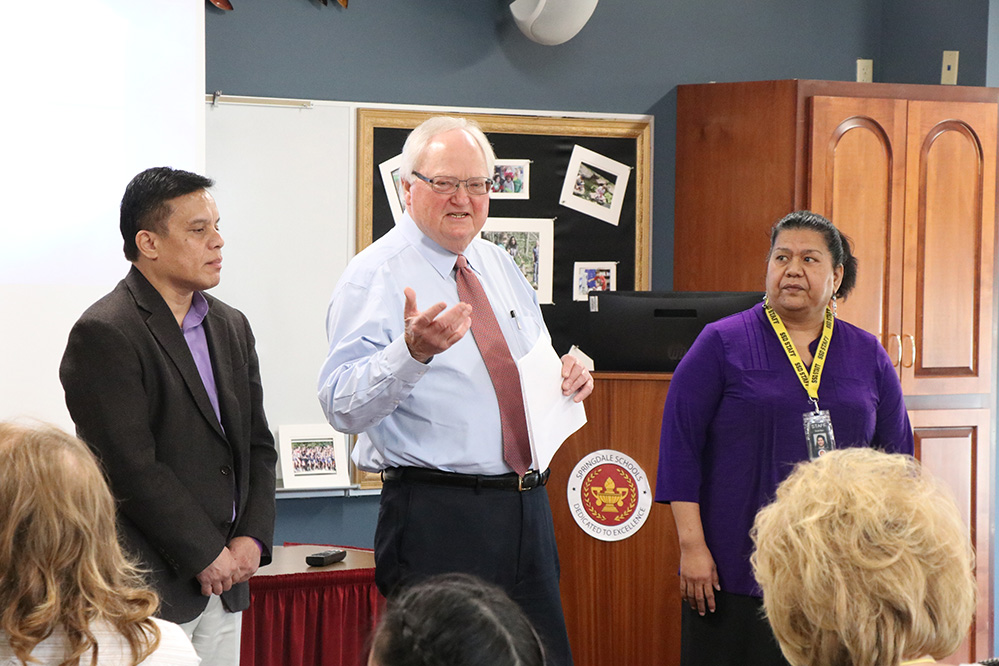

Former superintendent Jim Rollins witnessed the changes firsthand. When he joined the district in 1980, 3 percent of the roughly 5,500 students were non-white. When he stepped down in June, more than 66 percent of Springdale’s 22,100 students were of color. More than 35 percent of its students are English language learners. And nearly 3,000 students hail from the Marshall Islands, helping to make Springdale the largest Marshallese community in the U.S.

The disparities in language and culture have created a gulf that school officials — with help from students like Maddison — have worked to bridge. Until he left the district to become a college president, Rollins met monthly with Marshallese families, and the district produced dozens of videos to share information and highlight success stories in the Marshallese community. The district has also created a parent liaison job and hired Marshallese residents for a quarter of the positions.

The district, Rollins said in an interview prior to his departure, “went through an enormous process” to handle the immigrant population.

“We knew that as a team we didn’t have very many bilingual teachers, we didn’t have very many [English as a Second Language] certified teachers, we didn’t have intake systems to take students with various backgrounds into the system and serve them effectively right away,” Rollins said.

But the process hasn’t consistently yielded progress. The high school graduation rate for Marshallese students, 74 percent, is more than eight points below the district average, and these students are far more likely than their peers to be held back. Marshallese students are absent more often and are far less likely to take gifted and talented classes. And it’s almost guaranteed they will not have a teacher who looks like them: Only one of the district’s more than 1,400 teachers identifies as of Marshallese descent.

The roots of the exodus to Springdale trace back to the end of World War II, when the United States won control of the islands from Japan. In the 12 years following the war, the U.S. tested 67 nuclear weapons on the islands, most of which are uninhabited. As compensation, President Ronald Reagan signed an agreement in 1986 that permitted the island’s residents, who are not American citizens, to live and work in the United States without a visa.

One Marshallese man settled in Springdale and successfully found work, and word spread. Emigration to Springdale accelerated in the 1990s, both among Latinos, whose population there tripled between 1990 and 1995, and Marshallese. With the unemployment rate in the islands exceeding 30 percent, thousands of Marshallese flocked to Springdale for its low cost of living and plethora of employment opportunities. Tyson Foods, George’s and Cargill, which together employ more than 8,000 people, help make Springdale the “Poultry Capital of the World.” Between 2000 and 2010, the Marshallese population in Springdale skyrocketed by 294 percent.

Springdale Public Schools are a world away from what students experienced on the islands. In the Marshall Islands, some schools serve students only until the eighth grade. Enrollment is simpler. Immunizations are optional.

Maddison — who graduated from high school in Springdale, founded the Marshallese College Student Association and now works part time for the Marshallese Educational Initiative — believes that some of the students’ difficulties in school can be chalked up to cultural differences.

Take attendance, for example.

Marshallese students missed more school in the 2017-18 and 2018-19 school years than any other racial or ethnic group in Springdale, according to The 74’s analysis of data provided by the district. On average, they missed four more school days than Asian students, who had the highest attendance rates both years. Maddison identified an unusual culprit behind many of the absences: the church.

The Marshallese interpretation of Christianity is highly communal and participatory. Events run long and late. Lucy Capelle, the Marshallese pastor who leads Christ New Beginning Church in Springdale and has several children who attend the town’s schools, acknowledged in an interview that the school district has shared attendance data with local church leaders to solicit their help with the problem. Her church’s Sunday evening services used to start at 8:00 p.m. and stretch into the early morning hours, leading some students to miss school the next day. The church has since done away with its evening service in order to help boost attendance, but she said parents’ practices for Christmas events begin more than two months before the holiday and can also impact students’ attendance.

“[In October], they have Christmas practices, so they go and gather in a house or in the church, to practice their singing or their dancing,” she said. “They take their kids with them, and they take them for the night until 11 o’clock or 12 o’clock. The next day, they get tired, and they don’t realize that the time already passed to prepare their kids to send them to school, and their kids are also tired from staying up late in the night.”

For Maribel Childress, the parents’ choices seem logical. Childress had never heard of the islands when she was named principal of a Springdale elementary school that serves a large number of Marshallese students, but she learned quickly. She ended up taking two trips to the islands, which helped deepen her appreciation of the culture.

Childress offered an example of a Marshallese family who were planning to attend parent-teacher conferences until a fellow community member asked to borrow their car. Childress said the family would prioritize helping a fellow islander over attending the school conference because of the value the culture places on community and religion.

“Of course they’re going to choose that, because who do you want to be unhappy with you — Ms. Childress or God?” said Childress, who was named superintendent this spring of a small school district in northwest Arkansas. “If you’re going to make somebody mad, it’s going to be the principal, not the person that gives me eternal life.”

To help engage families in school life, the district created parent liaisons; in the 2019-20 school year, a disproportionate share of the positions — 10 of 41 — were filled by Marshallese, according to the district. Carlnis Jerry, who grew up on the islands and has lived in Springdale since 2010, is one of them. She’s also a program director at the Marshallese Educational Initiative. She spends as much of her time helping families as she does assisting school staff who need a better handle on Marshallese culture.

One key difference between the cultures, she explained, lies in the efforts made to ensure that students attend school. “On the islands, if you miss school, we don’t come to you, we don’t call you. If you show up, you show up. Here, it is very different.”

In recent years, the district has simplified its enrollment process and admitted more than 1,400 3- and 4-year-olds into pre-K, which will help young Marshallese students get acclimated to the public schools earlier. In addition, Springdale created what is now one of the most effective family literacy programs in the country, according to the National Center for Families Learning. Parents at 20 of the district’s 31 schools can come to their child’s school four days a week, for three hours a day, to learn English and parenting skills and spend time in their child’s classroom.

The district also launched summer school, not as a punishment for low performers but as a supplemental way to help Marshallese and other students learn more quickly. And it helped more than 40 percent of its 1,500 teachers become certified in English as a Second Language. The training focuses on supporting all non-native-English-speaking students, regardless of their primary language.

Rollins stresses that partnering with families from different backgrounds is a long game, and he preaches patience.

While not perfect, the district is taking positive strides, advocates say. Educators in three states have contacted Childress for advice about serving Marshallese students, and she and Jerry say progress is slow but visible.

“It takes a lot of work, but as soon as they trust you, they will open up to you,” Jerry said of Marshallese families. “Be patient and don’t get mad easily because we are very observant people. The tone and the way you act, that’s all it takes. We are very observant.”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)